Adapting at Fraser Common Farm Cooperative

Photos and text by Michael Marrapese

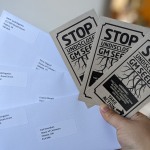

In 2018 Fraser Common Farm Co-operative—home of Glorious Organics—undertook a year long on-farm research project to explore how small farms could adapt to climate change. Seeing the changes in seasonal rainfall, climate predictions by Environment Canada, and new ground water regulations from the provincial government, the cooperative could see that water availability would eventually become a significant limiting factor in farming operations.

The discussions about adaptation were complex and multi-factored. Every operation on the farm is connected to something else and many systems interconnect in differing ways throughout the season. Changing practices can be difficult, time consuming, and sometimes risky.

During the year-long project, funded by Vancity, Co-op members worked to evaluate farming practices and areas of opportunity and weakness in farm management. The project generated several feasible solutions to decrease the demand on groundwater, buffer water demand, harvest rain water, and use irrigation water more efficiently. Some solutions were fairly straightforward and easy to implement. Others required more expertise, better data, and further capital.

Mark Cormier: Improving Water Practices

Mark Cormier explains how Glorious Organics uses edible, nitrogen fixing peas, and Fava beans for cover crops. He’s moved away from overhead spray irrigation to drip tape for the bulk of Glorious Organics’ field crops. He puts drip tape under black plastic row mulch. The plastic mulch significantly increases water retention and suppresses weeds. After the first crop comes off the field he rolls up the plastic and plants salad greens in the same row without tilling. Glorious Organics plans to double the size of the artificial pond and and dredge out a smaller natural spring basin to provide more water for the longer, drier summers the region is experiencing. Cormier notes that this year they are selling a lot of plums, a crop that they don’t water at all.

David Catzel: Developing Diversity

Catzel has several plant breeding and selection projects on the go to develop populations of productive, flavourful, and marketable crops. Preserving and expanding bio-diversity on the farm is vital for long-term sustainability. With his multi-year Kale breeding project, David has been seeking to develop a denticulated white kale and in the process has seen other useful characteristics, like frost-hardiness, develop in his breeding program. He’s currently crossing varieties of watermelon in order to develop a short-season, highly productive variety. His development of seed crops has also become a significant income source. He estimates his recent batch of Winter White Kale seed alone will net $1,500 in sales. As the Co-operative diversifies its product line to include more fruit and berries, organic orchard management practices have become increasingly important. Catzel has been instrumental in incorporating sheep into orchard management. A critical component of pest management is to keep the orchards clean and to remove any fruit on the ground to reduce insect pest populations. The sheep eat a lot of the fallen fruit and keep the grass and weeds in check making it easier to keep the orchards clean.

Barry Cole: Gathering Insect Data

With the arrival of the spotted wing drosophila fruit fly, Fraser Common Farm was facing a management crisis. There seemed to be little organic growers could do to combat the pest, which destroys fruit before is is ripe. Infestations of Coddling Moth and Apple Maggot were making it difficult to offer fruit for sale. Barry Cole set about to gather meaningful data to help understand pest life cycles and vectors of attack. He’s set up a variety of traps and tapes and monitors them regularly to determine when pests are most active and which trees they prefer. The “Bait Apples” attract a large number of Apple Coddling Moths. The yellow sticky tapes help determine which species are present at various times in the season. Since many of the fruit trees are more than 20 years old, he also monitors and records tree productivity and fruit quality to better determine which trees should be kept and which should be replaced.

Michael Marrapese is the IT and Communications Manager at FarmFolk CityFolk. He lives and works at Fraser Common Farm Cooperative, one of BC’s longest running cooperative farms, and is an avid photographer, singer, and cook.

Feature image: David Catzel’s watermelon varieties.

Clockwise from left: ; the fake apple trap; identifying active pests; Barry Cole inspects walnutd for pests; Mark Cormier with fava bean cover crop; plums in the upper orchard; David Catzel with his White Winter Kale seed crop. Credit: Michael Marrapese.