Revision of the Canadian Organic Standards

By Nicolas Walser

It’s that time again: the review of the Canadian Organic Standards!

Every five years, the Canadian Organic Standards undergo a revision and an updated version is published. Organic standards need to evolve to address emerging challenges, technological advancements, and scientific research. The last revision was published in 2020—always be sure you are referring to the most up-to-date version.

You may be asking, “If revisions occur every five years, don’t we have some time before the 2025 version?” The reality is that updating the standards is quite a lengthy process and requires input from many stakeholders.

The Canadian Organic Standards are held by the Canadian General Standards Board (CGSB) and maintained by the Organic Federation of Canada (OFC) but are ultimately “owned by the public.” This means that it is the public and industry, not the government, who gets to make and set the standards. So, anyone can be involved in the revision process.

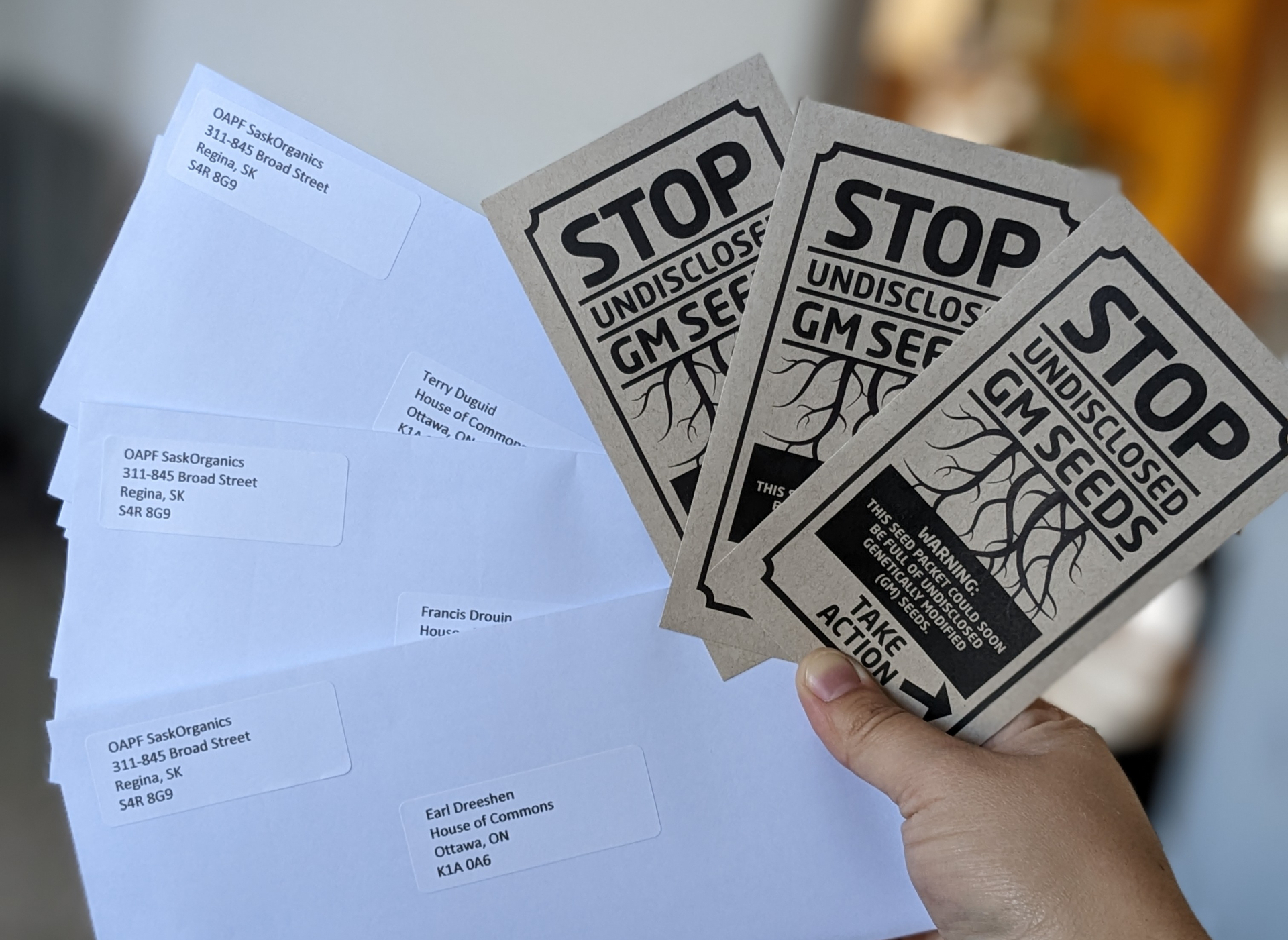

The revision process is spearheaded by the OFC, starting by receiving proposals from the public; this began in July 2023, and 290 proposals have been received. OFC then convenes seven Working Groups to discuss the proposals, each focused on a specific area of organic production (crops, livestock, etc). Each Working Group is made up of 15 members and contains numerous producers, as well as consultants, organic stakeholders, and at least one verification officer or representative of a certifying body.

Within a Working Group there are Task Forces made up of specialists and focused on specific areas of the standards, such as poultry or mushrooms. They discuss proposals in great detail and bring their recommendations to the larger Working Group.

After the Working Groups have assessed the proposals and come to a consensus, their recommendations are sent to the CGSB’s Technical Committee on Organic Agriculture. The Technical Committee is made up of volunteers who represent organizations from across Canada, including industry groups and provincial associations. There are voting and non-voting members; non-voting members provide input and technical expertise but are unable to vote on the adoption of the standards. Once the Technical Committee has made its decisions the new draft standards will be opened up for public comment in 2025.

Organic BC has the privilege to be a voting member of the Technical Committee. This is a very exciting opportunity for our organization to have a seat at the national table. As the first province in Canada to have had a provincial organic standard—the BC Certified Organic Program was created in 1993 and was foundational to the creation of the National Standard—we have lots to offer the rest of the country.

Involvement in the revision process allows Organic BC to contribute to the development of standards that not only meet regulatory requirements but also enhance consumer trust in the authenticity and integrity of organic products. Organic BC will be able to contribute valuable insights on how the standards can be adapted to better suit the specific conditions of BC’s unique and diverse organic sector. BC requires a set of standards which are robust and empower our producers to continue in our mission “To cultivate a resilient organic movement in British Columbia.”

I am very excited to be able to represent Organic BC on the Technical Committee. I don’t take this responsibility lightly, as our industry relies on these standards. Organic BC’s executive director, Eva-Lena Lang, and I will be having regular meetings throughout the revision process to ensure that our votes align with the needs of the organic community in BC. I encourage everyone to review the 290 proposals that have been submitted for consideration for the revisions.

Each proposal will have to be assessed and discussed, which is why the revision process takes such a long time. This rigorous process relies on many volunteers contributing a significant amount of effort to ensure that the standards continue to be robust and reflect IFOAM Organics International’s Principles of Organics (Health, Ecology, Fairness, Care).

I am looking forward to undergoing this work in a manner that fosters collaboration and ensures that the standards are developed through a consultative and inclusive approach, taking into account the perspectives of our various stakeholders.

Your input is crucial throughout this process, both now in reviewing the proposals, and later, when the draft is released for public comments. The sooner we have your input, the more time we will have to devote to ensure that the revisions reflect the needs of our community.

You can view the proposals at the Organic Federation of Canada website:

- Proposals for changes to Organic Principles and Management Standards – CAN/CGSB-32.310

- Proposals for changes to Permitted Substances Lists – CAN/CGSB-32.311

If you have comments on any of the proposals, please share your feedback with Organic BC by emailing info@organicbc.org.

Nicolas Walser (he/him) is an agrologist who lives and grows in unceded Ktunaxa territory with his family. A seed saver, wetland enthusiast and policy nerd he sits on Organic BC’s Accreditation Board and the Central Kootenay Food Policy Council.

Featured image: Peppers ripening at Northstar Organics. Credit: Maylies Lang.