Gene Editing: The End of GMOs?

Lucy Sharratt

There is a lot of excitement about “gene editing,” or genome editing, in the media and research community. In the farm press, genome editing techniques are being widely described as precise and, in some cases, non-GMO. Neither is correct.

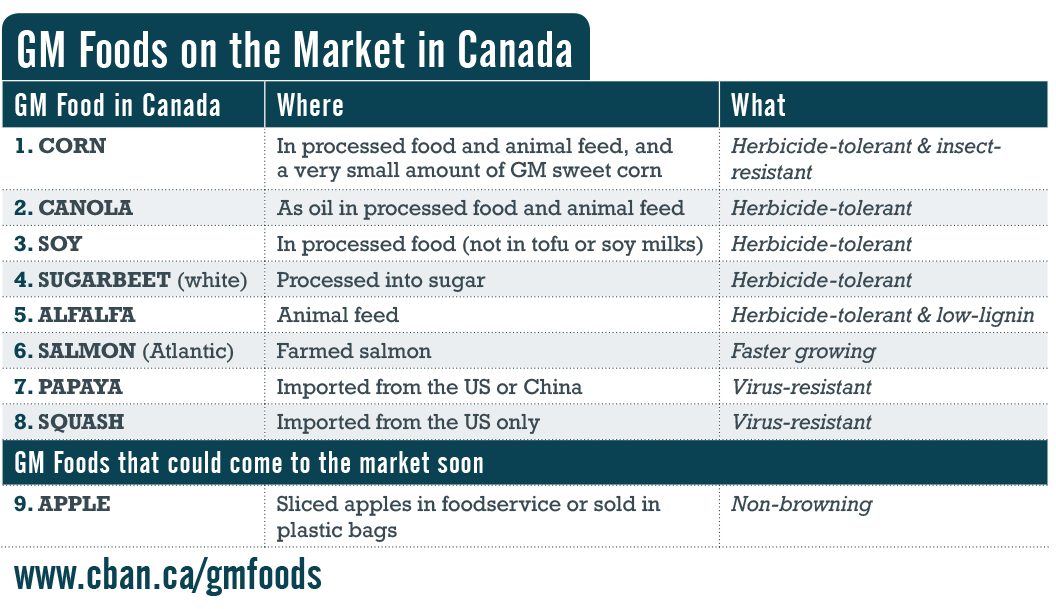

Genome editing techniques can be used to alter the genetic material of plants, animals, and other organisms. They aim to insert, delete, or otherwise change a DNA sequence at a specific, targeted site in the genome. Genome editing techniques are a type of genetic engineering, resulting in the creation of genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

The techniques are powerful and could lead to the development of more genetically modified (GM) crop plants, and even GM farm animals. However, the hype surrounding genome editing is similar to what was seen with first-generation genetic engineering. Most news stories about new products are actually about experiments in very early stages, which may never lead to new foods on the market.

Just as with first-generation genetic engineering, genome editing techniques are moving quickly in the lab to create new GM foods, even while our knowledge about how genomes work remains incomplete. The techniques are powerful and speedy, but can be imprecise and lead to unexpected consequences.

The genome is the entire set of genetic material in an organism, including DNA.

What is Genome Editing?

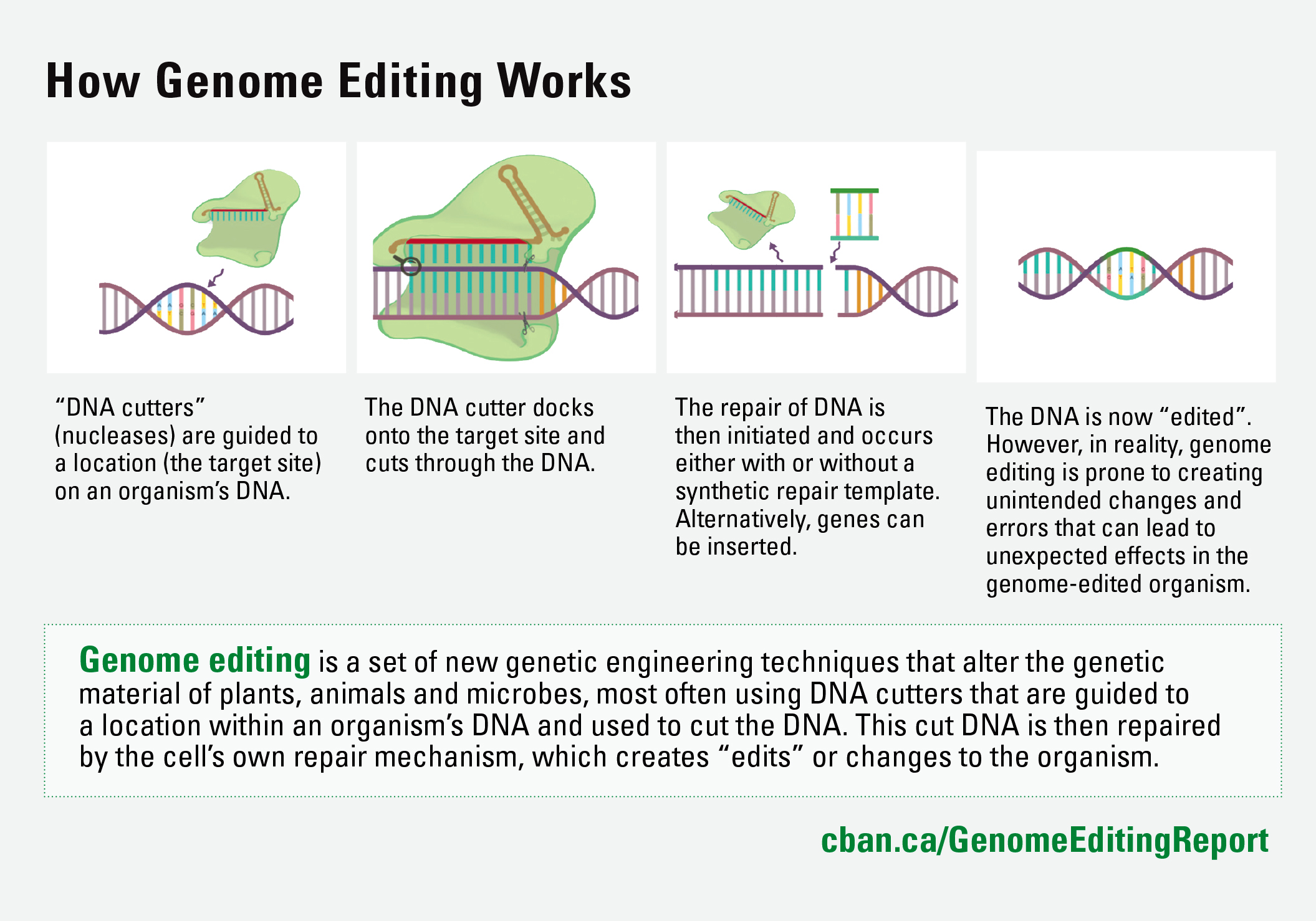

Genome editing most often uses DNA “cutters” that are guided to a location within an organism’s DNA and used to cut the DNA. This cut DNA is then repaired by the cell’s own repair mechanism, which creates changes or “edits” to the organism. The most frequently used genome editing technique is called CRISPR, but other techniques follow similar principles.

First-generation genetic engineering techniques insert genes at random locations. These genes then permanently become part of the host organism’s genome, creating new DNA sequences. In contrast, new genome editing techniques insert genetic material that is then guided to a specific target site to perform “edits.” This means that, with genome editing, the inserted genetic material makes changes to the genome but does not necessarily have to become incorporated into the resulting GMO and can be bred out. This means that not all genome-edited GMOs are transgenic.

This also means that, unlike all first-generation GMOs, not all genome-edited GMOs are transgenic (have foreign DNA). The ability to create non-transgenic organisms is often stressed by the biotechnology industry as an advantage to using genome editing but, as discussed below, whether or not a GMO is transgenic is not the chief concern about genetic engineering.

There is one genome-edited organism on the market in Canada: an herbicide tolerant canola from the company Cibus (Falco brand). This GM canola, like all other GMOs, is prohibited in organic farming and excluded from “Non-GMO Project” verification. However, despite also being regulated as GM in Europe, the company Cibus still sometimes refers to this non-transgenic canola as “non-GMO.” This one example provides a glimpse into how the biotechnology industry would like to shape the regulation and public perception of genome editing to avoid the GMO controversy.

Unexpected and Unpredictable Effects

Genome editing can be imprecise, and cause unexpected and unpredictable effects. Many studies have now shown that genome editing can create genetic errors, such as “off-target” and “on-target” effects:

- Genome editing techniques, such as the CRISPR-Cas9 system, can create unintended changes to genes that were not the target of the editing system. These are called “off-target effects.”

- Genome editing can also result in unintended “on-target effects,” which occur when a technique succeeds in making the intended change at the target location, but also leads to other unexpected outcomes.

- Genome editing can inadvertently cause extensive deletions and complex re-arrangements of DNA.

- Unwanted DNA can unexpectedly integrate into the host organism during the genome editing process. For example, foreign DNA was unexpectedly found in genome-edited hornless cows.

Despite these many potential impacts, there are no standard protocols yet to detect off-target and on-target effects of genome editing.

Sometimes intended changes that are created by genome editing techniques are described as “mutations,” because only very small parts of DNA are altered and no novel genes have been intentionally introduced. However, even small changes in a DNA sequence can have big effects.

The functioning of genes is coordinated by a complex regulatory network that is still poorly understood. This means that it is not possible to predict the nature and consequences of all the interactions between altered genetic material and other genes within an organism. For example, one small genetic change can impact an organism’s ability to express or suppress other genes.

An End to GMO Regulation?

Despite these risks, a number of researchers and companies are arguing that genome editing should be less regulated than first-generation genetic engineering, or not regulated at all.

It is commonly argued that regulation is an obstacle to innovation. In relation to genome-edited animals, the argument has been made that mandatory government safety assessment “makes no economic sense.”1 Instead, industry argues that the process by which new plants and animals are created should be irrelevant to safety considerations. This is why US government proposals to assess the safety of all genome-edited animals were called “insane” by one of the developers of genome-edited hornless cows2—three years before the cows were found by US government scientists to contain unexpected foreign DNA.

New genome editing techniques will challenge regulators with new traits and processes, with increasing complexity and ongoing uncertainty. Rather than assume their safety, these new technologies need to be met with precaution and increased independent scrutiny.

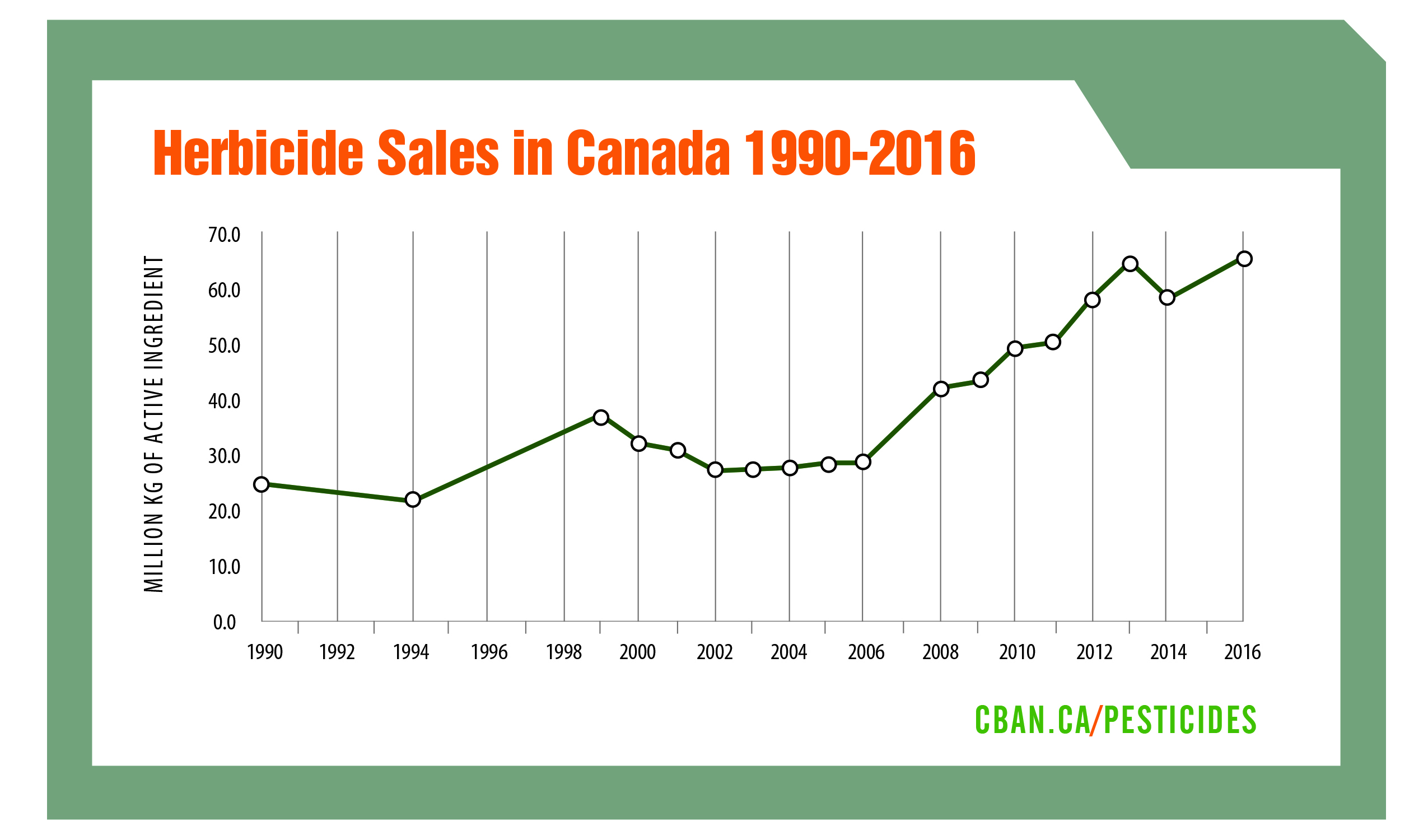

Even more fundamentally, our government must consider the question of social worth before

approving products of genetic engineering. Without consulting Canadian farmers, for example, companies can commercialize new GM products (such as glyphosate-tolerant alfalfa) that have few benefits but can, on the contrary, pose serious risks to farming systems and the environment.

For references and for more information and discussion about genome editing, read CBAN’s new report, “Genome Editing in Food and Farming: Risks and Unexpected Consequences.” The report and an introductory factsheet are available online.

For updates or to find out more, visit CBAN online.

Lucy Sharratt is the Coordinator of the Canadian Biotechnology Action Network (CBAN). CBAN brings together 16 groups (cban.ca/about-us/members/) to research, monitor and raise awareness about issues relating to genetic engineering in food and farming. CBAN members include farmer associations, environmental and social justice organizations, and regional coalitions of grassroots groups. CBAN is a project on MakeWay’s shared platform.

Featured image: Canola in bloom. Credit: Bellingen2454 (CC)