Building a Relationship-Oriented Approach to Research

Effects of Organic Amendments on Soil Health Indicators in an Indigenous Farm in the Northern Peace River Region of Canada

By Tiffany Traverse

[Editor’s note: This research was presented at the First International Forum on Agroecosystem Living Labs, October 4-6, 2023, Montréal, QC, Canada, and is shared here with gratitude. This article was prepared with the support of Tiffany Traverse for the BC Organic Grower—the full research team is credited at the end of this article, with thanks.]

Indigenous knowledge is cumulative, holistic, dynamic, and inclusive of all variants of knowledge, including, but not limited to, science, cosmology, spirituality, language, politics, and law. It is relationship-oriented, place-based, intergenerational, and validated by lived experience and time.

The historical, cultural and socio-economic context of Indigenous agriculture is different from the context of conventional agriculture. Some Indigenous farmers practice closed loop organic farming by recycling nutrients within their system. The belief of “everything is connected” is the key concept that “soil and soul” are connected, and thus should be honored to sustain the life in continuum.

Closed loop farming guarantees carbon returns to a local system. The benefits of closed loop farming include:

- Increased soil carbon sequestration;

- Increased biodiversity;

- Increased nutrient availability; and

- Reduced pest and disease issues.

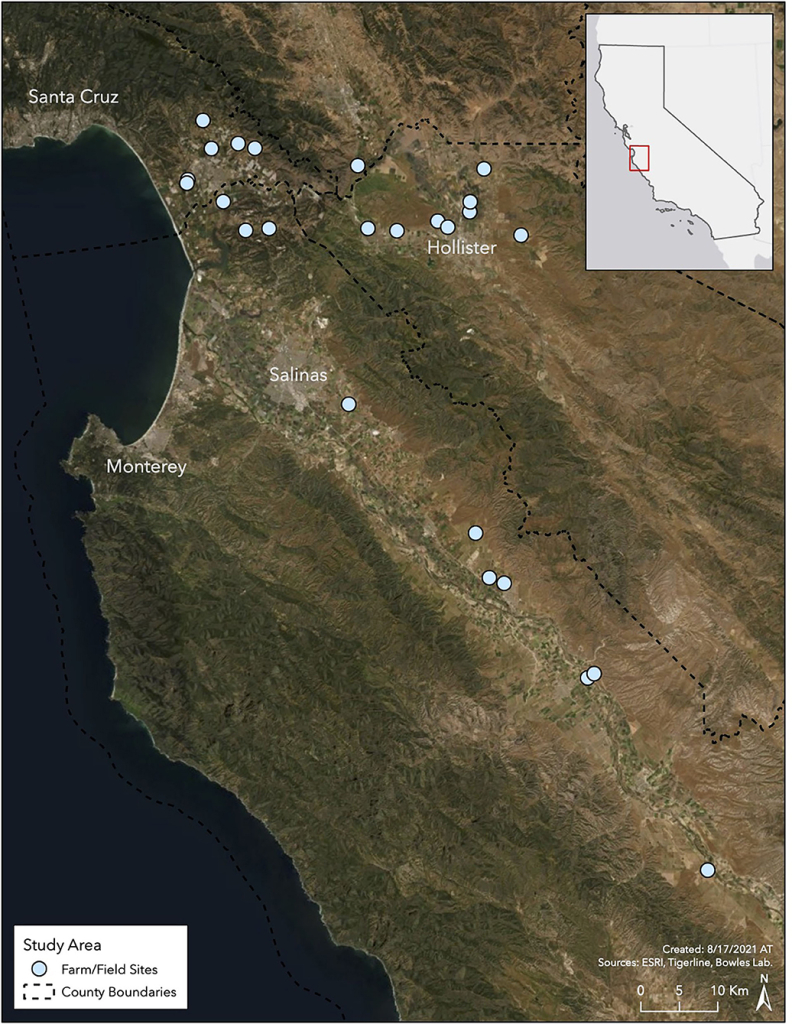

Maintaining soil health and fertility development is the key for sustainability of agriculture and food security. Indigenous communities have been practicing farming based on traditional skill and knowledge since time immemorial. With an aim to allow Indigenous communities to integrate western science into their Indigenous knowledge, a study on evaluating the soil health and quality was carried out at Fourth Sister Farm in Progress, BC. Effects of five different type of farmyard manure (FYM), namely, bovine, swine, equine, poultry, and vermi-compost on soil health indicators, were tested in a two-year pilot project from 2021-2023.

In addition to better understanding the effects of the five different manure types on soil health, the study also sought to develop a greater understanding of Indigenous community research priorities related to Indigenous agriculture, which can support the co-creation of larger strategic research collaborations.

Material and Methods

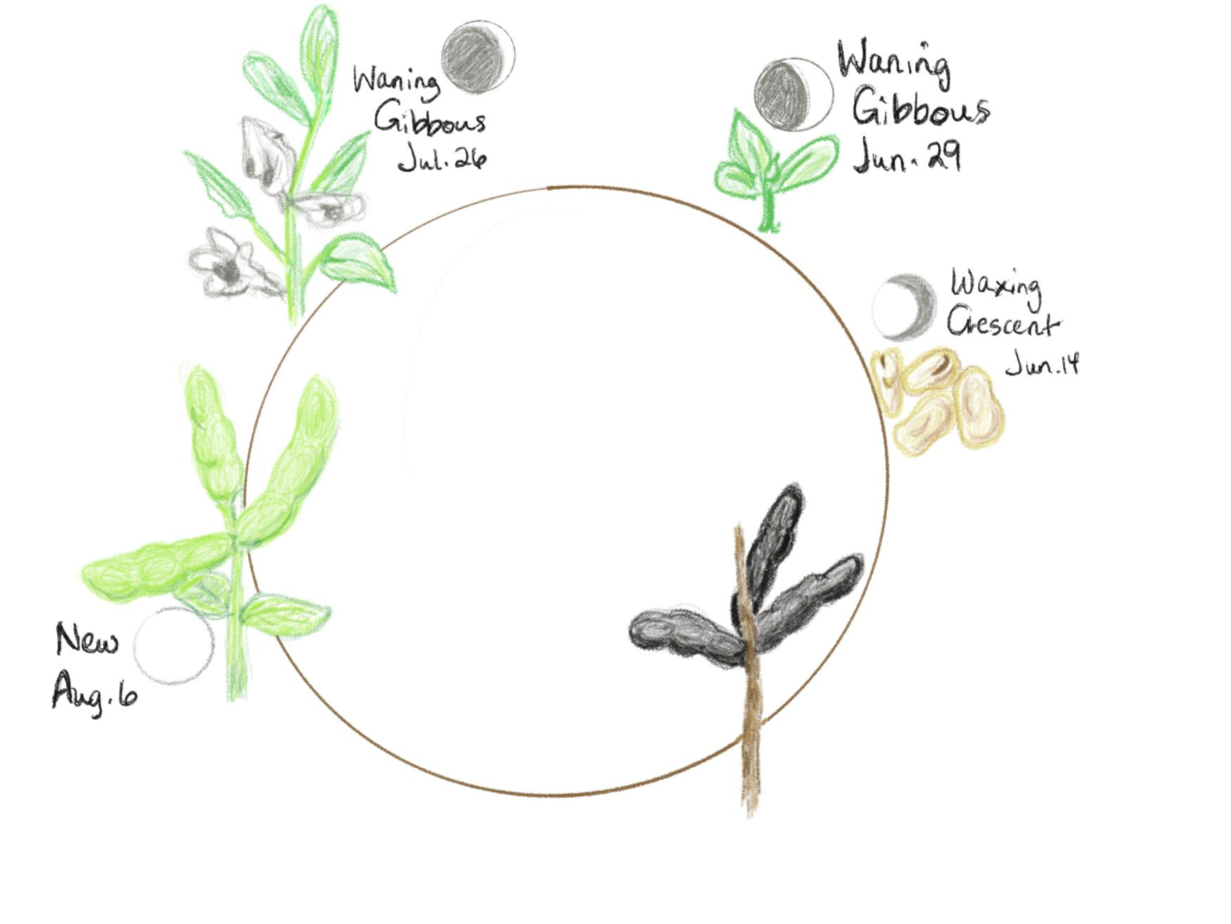

The study followed a decolonial approach to research, from consultation, co-development, and execution by the Indigenous farmer. This included plot size, seed and seeding techniques, traditional/manual, and phenology, resulting in food and seed.

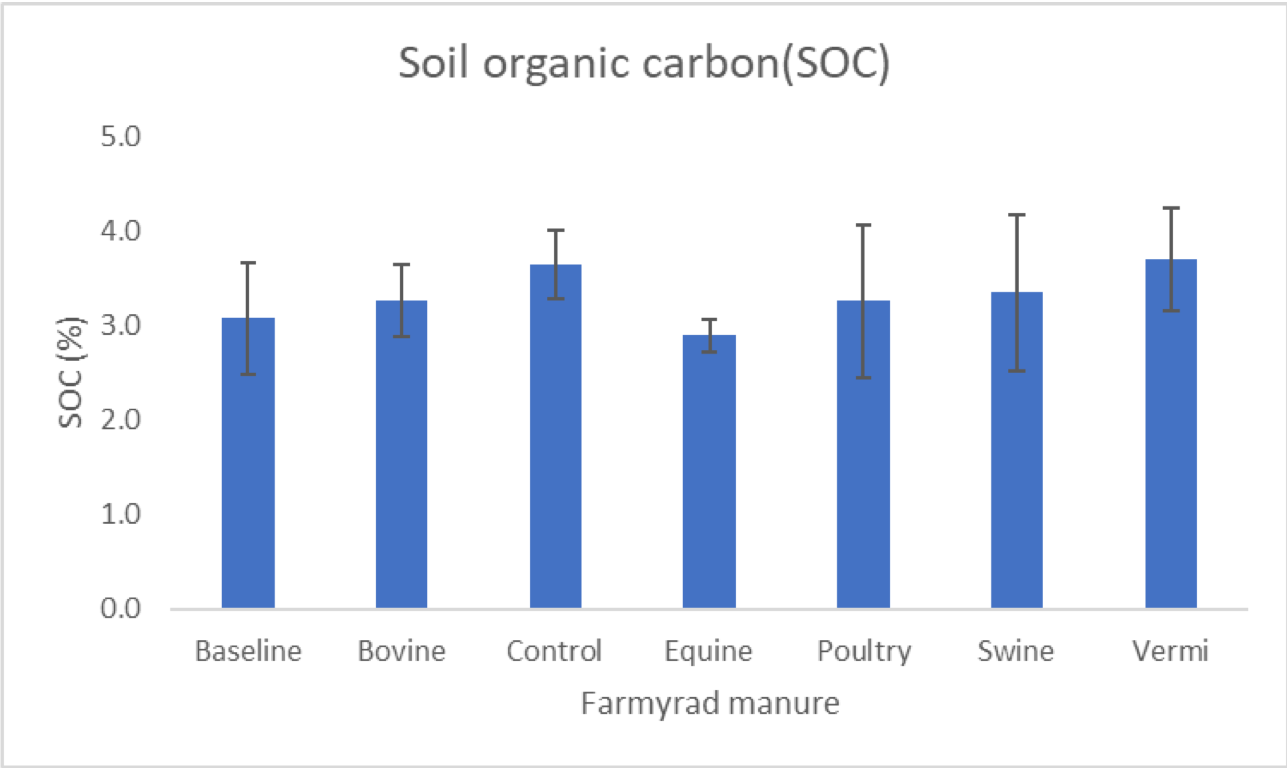

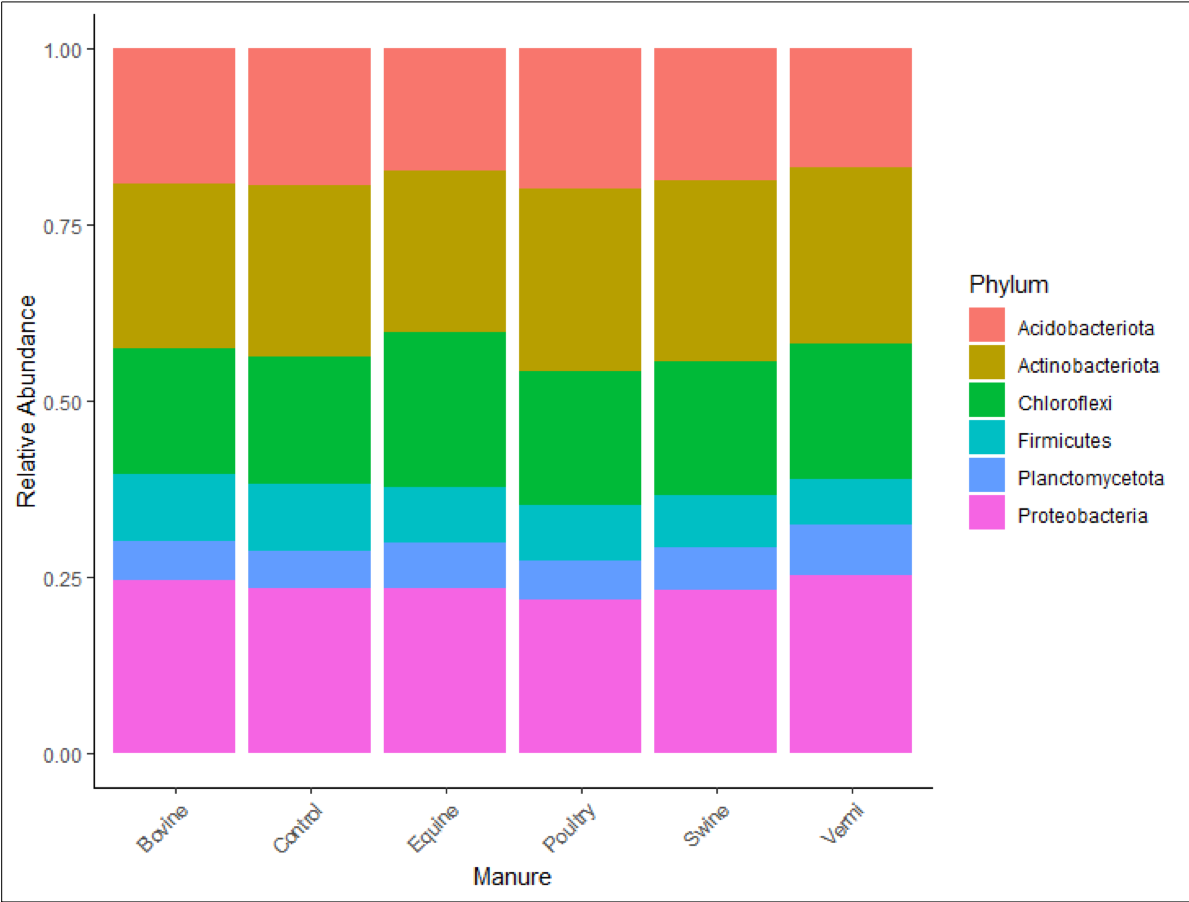

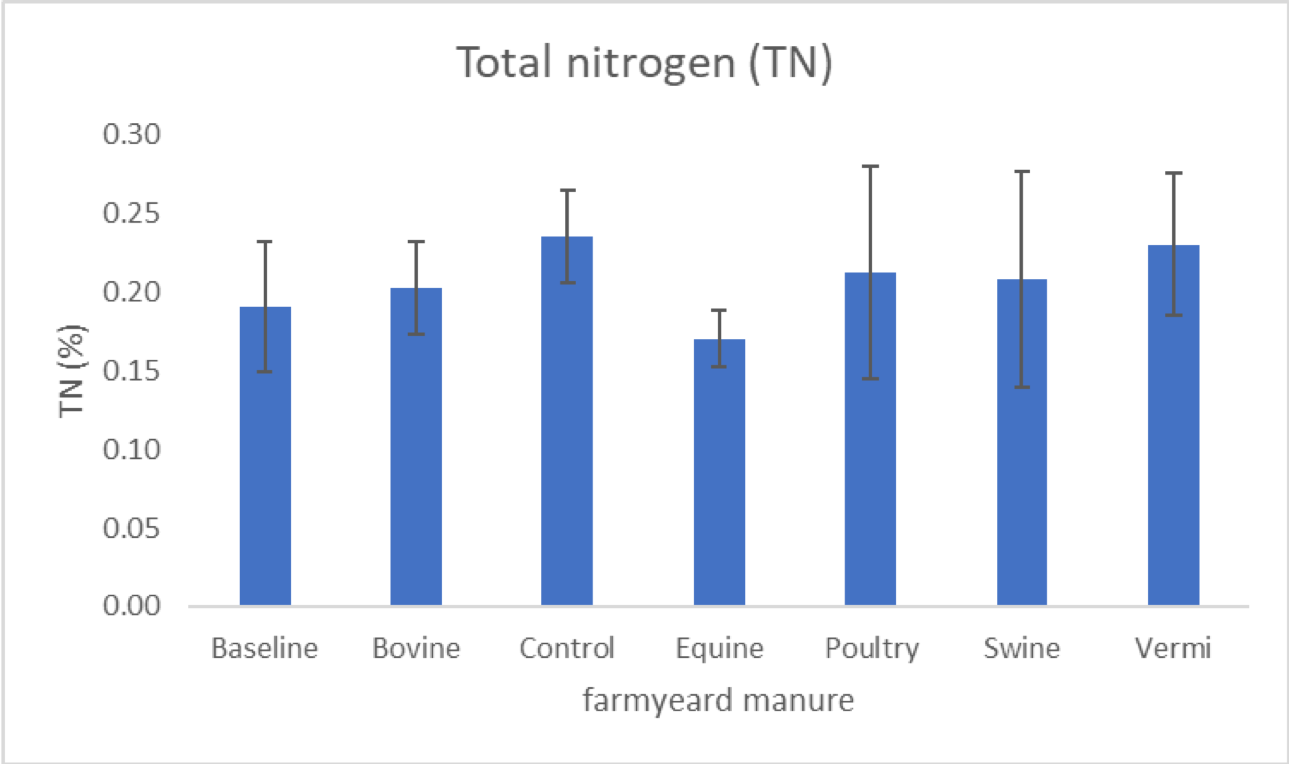

The crop investigated in the first year was Fava bean (Vicia faba), and the second-year crop was oats (Avena sativa). Soil samples were collected before seeding of crops for baseline data on soil health and nutrients. Next, five FYM treatments and one control plot were replicated four times following complete random block design. Rhizosphere sampling was carried out during the peak growing season (mid-July/August), and final soil sampling was collected immediately after the harvesting in September in each year. Soils were tested for key soil health parameters: soil organic carbon (SOC), total nitrogen (TN), aggregate stability, microbial biomass, bacterial/fungal diversity, and biomass in the rhizosphere.

The results of soil tests revealed the following:

- Soil health parameters did not differ by FYM type by the end of two growing seasons (P > 0.05);

- Bacterial relative abundance was not impacted by manure application type;

- Fungal richness only responds with vermi-compost;

- Aggregates were more stable in vermi-compost treated soils; and

- Richness may have increased between years, but sample analysis methods may be confounding the results.

Overall, the study found no impact of different FYM treatments on the following soil health indicators: aggregate stability, SOC, mineralizable carbon, microbial biomass carbon (MBC), and root colonization. There was little impact of manure on fungal community structure after only one season.

More time is required to see community shifts and change in soil health indicators.

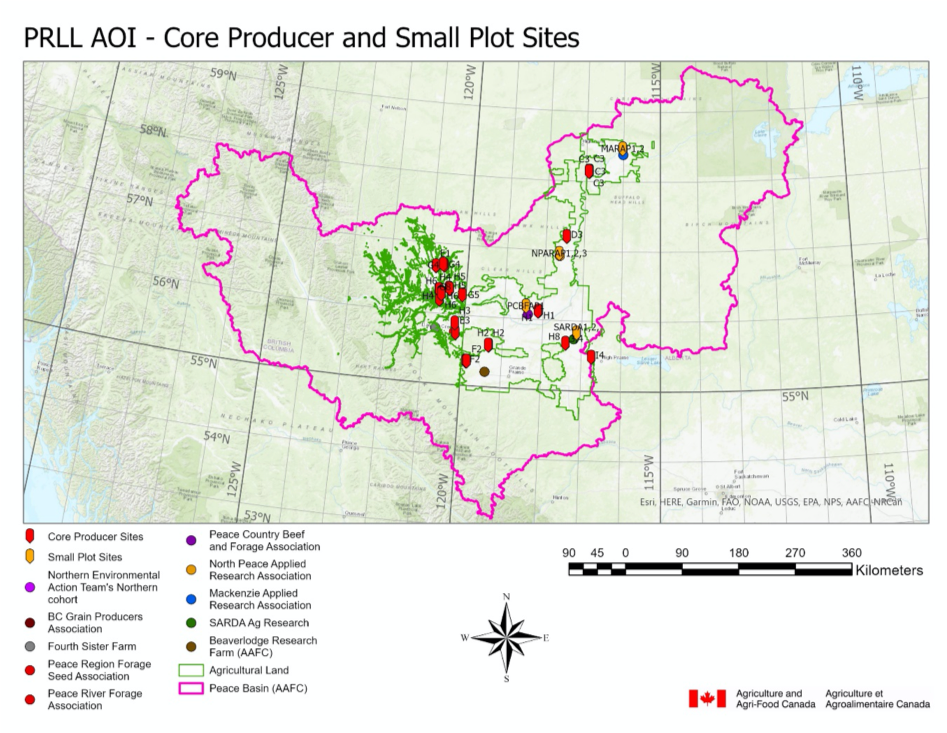

Fourth Sister Farm is collaborating with the Peace Region Living Lab. Agricultural Climate Solutions-Living Lab is a producer-led innovation project supported by research to store carbon and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Peace region Living lab is a AAFC funded five-year project (2022-2027) with the goal to “Enhancing Agroecosystem Services in the Peace River Region.”

This research was conducted by: Erin Hall (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada), Tiffany Traverse (Fourth Sister Farm, Progress, British Columbia), Patrick Neuberger (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada), Monika Gorzelak (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada), Bharat Shrestha (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Beaverlodge Research Farm, Beaverlodge, Alberta).

Acknowledgements: Greg Semach; Denis Belisle; Sarah Preston; Andrea Brown; Sam Nahli; Noabur Rahman; Stewart Garson; Irene Murray

This initiative was funded by the Indigenous Science Partnership Program (IASPP) of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Featured image: Shelling beans. Credit: Tiffany Traverse.