Organic Stories: Mackin Creek Farm

Rob Borsato with thanks to Marjorie Harris

Growing a Local Food Movement in the Cariboo

It was the “back to the land” movement of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s that nudged, on separate paths, Cathie Allen and Rob Borsato to the Cariboo. Together, in 1985 they purchased 105 acres of mostly timbered bench land above the Fraser River about 45 kilometres north of Williams Lake.

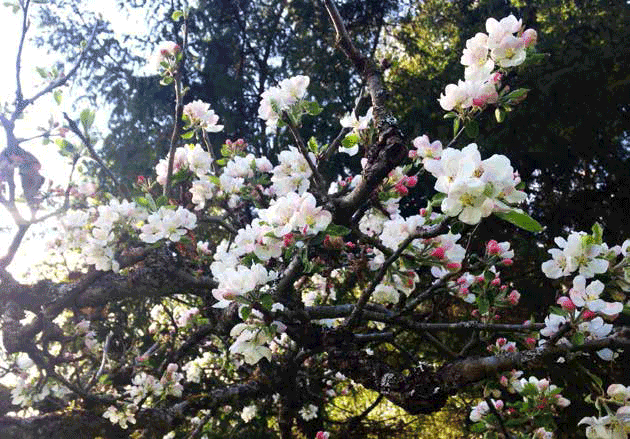

Immediately, they were captivated by the dramatic vistas, the arid climate, the light, silty soils, the bunchgrass hillsides, the open Douglas fir forests laced with juniper and sage, and Mackin Creek itself, which cut a deep swath through the middle of the property as it tumbled aggressively to the Fraser.

“Like any couple starting out with a piece of raw land, we were swamped with priorities—shelter and fences for animals, shelter for us, breaking some land, and, most challenging of all, developing irrigation and domestic water”, recalls Rob. Getting water up from the creek, a full 100 metres below, proved to be the biggest obstacle, especially since electricity was still several kilometres down the road. “Initially, we used a hydraulic ram, which harnesses the power of a large flow of falling water to push a smaller volume up hill. With some engineering, a fair amount of infrastructure, and a lot of tinkering, it served us well for a few years, until our farm needs outgrew the capacity of the pump.” “By then”, adds Cathie, “we had saved up the money to put in a permanent gravity feed system, with over a kilometre of buried pipe. It still works beautifully.”

During those early years, Rob continued to work as a horse logger, living away at camp all week, farming on weekends, and taking full advantage of spring “break up” to do the farm field work. To initially break the land, they used four big horses (black Percherons) and a heavy duty, single-bottom breaking plough. “It took two of us, one on the plough handles and the other driving the horses, and it was always exciting. We broke an additional half acre each season, for 10 years or so. We broke a lot of other stuff, too”, he quipped.

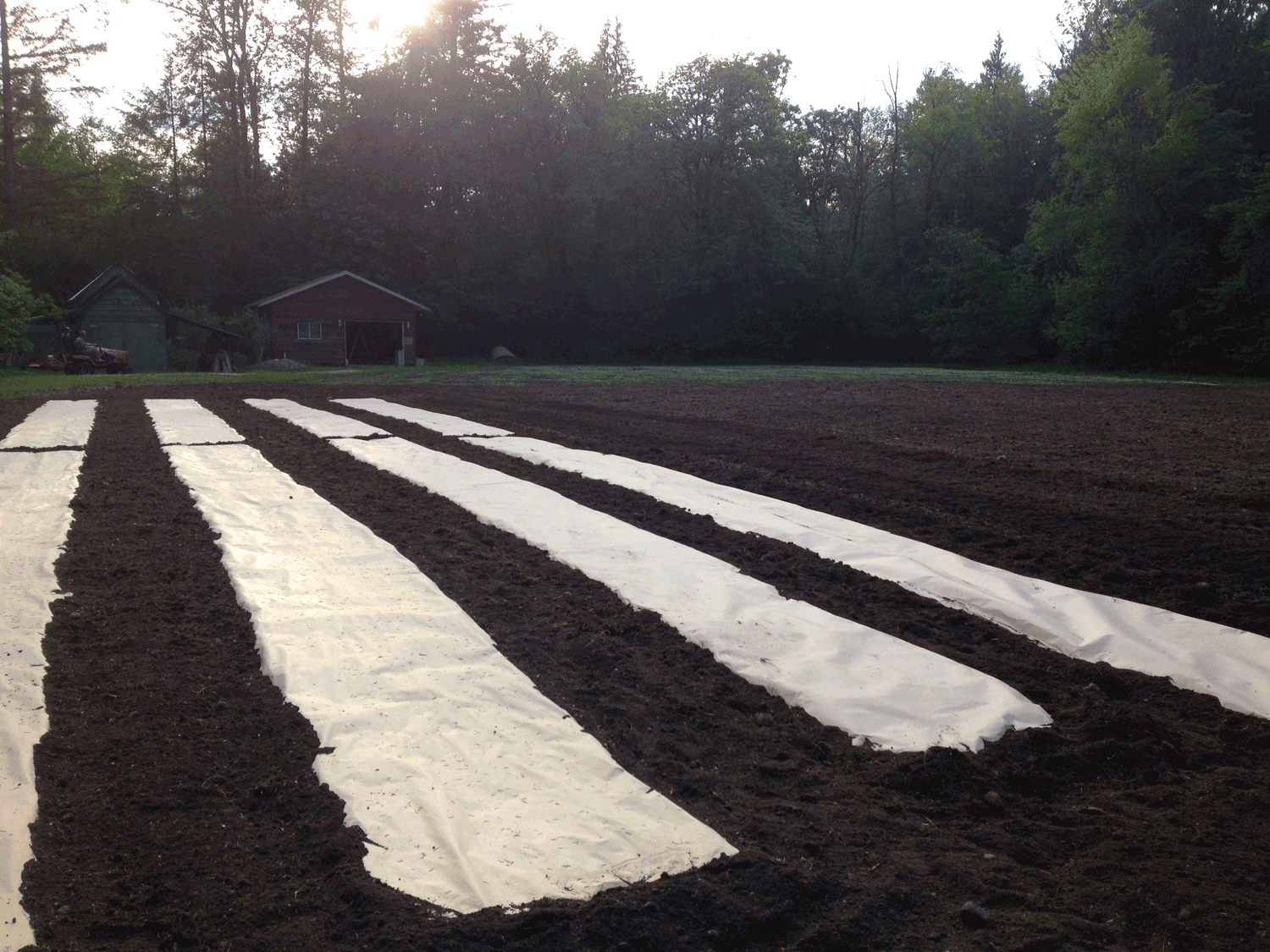

Rob hasn’t horse logged for over a decade now, but still uses the horses to do the heavy work on the farm, including all the discing, compost spreading, any ploughing, harrowing, planting and hilling potatoes, all the cultivating between rows and beds, and getting firewood for home and the greenhouse boiler. “For us, with a five acre organic garden, the horses are a perfect fit: not only do they supply the essential components of soil fertility, but they do the heavy lifting, and they provide for me an enjoyment that is very personal and enriching, even on bad days.”

Cathie worked off farm as a draught person prior to the birth of their son, Joe; she added the role of teacher when they elected to home school him. And, not unlike other farm-raised kids, Joe played a significant role on the farm for most of his youth, even coming home to work summers during undergraduate years. “We were so lucky to be able to have all that extra time with him, especially in light of the fact that the farming lifestyle can be so demanding”, reflects Cathie.

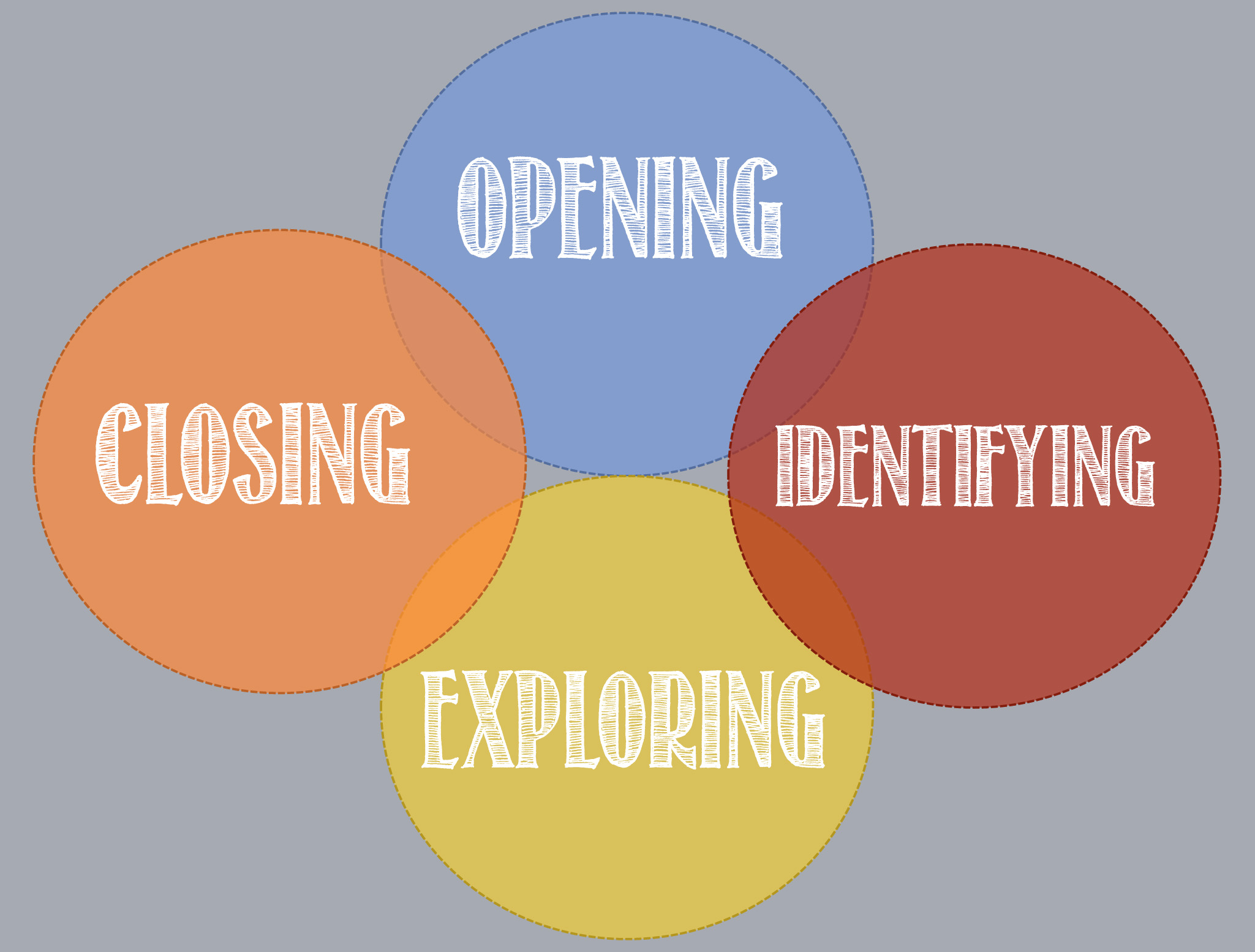

‘Demanding’ might well be a classic understatement, especially in those developmental years on the farm. “We quickly came to realize that the challenges were bigger than we were”, recalls Cathie, “and only by working cooperatively with others would we all have a chance of success”. The challenges lay not only with learning how to grow food, but how to market it as well. On this front, there was no infrastructure in place, no local farmers’ market, little awareness of local food, no talk of CSAs, no organic certification.

But there was, in the Cariboo, a nascent but enthusiastic group of young and aspiring farmers/ back-to-the-landers who shared common goals and principles. Together in 1988, they formed the producers’ group that would grow and eventually host the Quesnel Farmers’ Market. About the same time (and likely organized by Paddy Doherty), they were meeting on Sunday afternoons on little farms at the end of dirt roads to begin the formation of the Cariboo Organic Producers Association. A few years later, some of these same people convened in Kamloops to help create the BC Association of Farmers Markets. “And, at the same time, we were trying to figure out which varieties of garlic grew best, and how were we ever going to get rid of all those zucchini”, laughs Cathie.

For the first few years, the farms and the farmers’ markets in Williams Lake and Quesnel seemed to be growing slowly and with some synchronicity, “Then, in the early 90’s, farm production was outstripping demand, so they had to look at other marketing approaches. They learned what they could about CSAs, and partnered with Dragon Mountain Farm out of Quesnel, and introduced the concept to the Cariboo. “It caught on quite quickly, and eventually each farm was delivering 100 boxes a week”, says Cathie. “Shortly after getting this established, we saw the local food movement emerge, along with the exponential growth of organics, and the generally increased awareness consumers seemed to develop toward food. All of us who had been at this for awhile were positioned well to take full advantage of the additional consumer demand”.

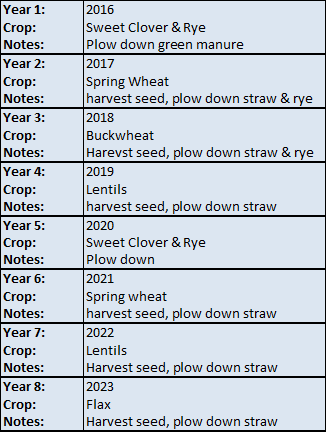

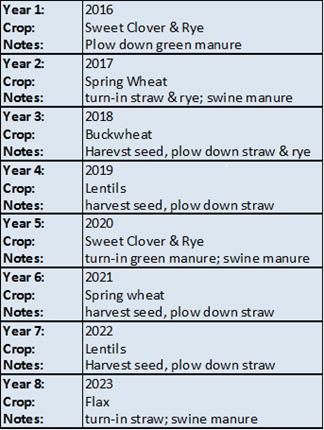

At this point, with the security of a committed CSA group, and a strengthening local farmers market, they were able to focus on ramping up per acre productivity. “Simply put, we learned something from our mistakes every year”, chuckles Rob; “What we did learn early on was how important soil fertility is to the success of the whole operation. So we figured out how to make good compost and are religious about applying it, we incorporate pigs and chickens into our rotation, and we use green manure crops whenever we can”.

The importance of feeding the soil, and the broader perspective of holistic land management, are some of the most fundamental lessons they impress upon interns. Several of these apprentices have gone on to develop their own successful farming operations, and this has been a real measure of gratification for Rob and Cathie. “These success stories are very uplifting”, attests Cathie, “in so very many ways, including the simple fact that more acres are being farmed organically”. They continue to share farming knowledge within their community. These include weekend workshops on organic farming, evening garden club talks, and elder college courses. Currently Rob is also doing consulting work with three local First Nations Bands to develop community gardens.

Now, nearly 30 years since they started farming, Rob and Cathie are talking about more changes. “We’re going to scale back our production to about two acres, not rely on full-time employees, and hopefully be able to build into it all some flexibility so that we can get a bit of time off in the summer months. We have two wonderful granddaughters, with whom we’d love to go camping once in awhile”, says Rob. “We’d like to find that sweet spot where we can continue doing what we love to do, just maybe a little less intensely”, concludes Cathie.

In addition to operating, with partner Cathie Allen, Mackin Creek Farm, on the west side of the Fraser River north of Williams Lake, Rob is involved with several regional agricultural organizations. Mackin Creek Farm was recognized by the BC Association of Farmers Markets as “Vendor of the Year” for the 2014 season.

I decided to stick with the traditional horizontal design I was experienced with, and build a mill. I ordered a set of 12” granite stones from Meadows Mills, bought a motor, pulleys, bearings and had a shaft machined locally. I made a trade with a sawmilling neighbour for a pile of dried birch he had in his basement for a furniture project he hadn’t gotten to. For the mill design, the beauty is in the simplicity.

I decided to stick with the traditional horizontal design I was experienced with, and build a mill. I ordered a set of 12” granite stones from Meadows Mills, bought a motor, pulleys, bearings and had a shaft machined locally. I made a trade with a sawmilling neighbour for a pile of dried birch he had in his basement for a furniture project he hadn’t gotten to. For the mill design, the beauty is in the simplicity.