Why Your Food Choices Matter

CBAN’s New Public Education Tool to Support the Organic Solution

Lucy Sharratt

The gravity and gathering speed of the global climate and biodiversity crises threaten to paralyze many people who want to make meaningful change but don’t know where to start. Thankfully, organic farmers are already implementing concrete solutions that everyone can support. In the face of climate emergency, organic farmers show us what is possible.

That’s why, at the beginning of this year, the Canadian Biotechnology Action Network (CBAN) started a new public education program to support organic farming. It centres around a new pamphlet called “Why Your Food Choices Matter,” which is designed for farmers to hand out at farm stands, farmers’ market tables, or in CSA boxes, and for distribution at health food stores and local events. The goal is to help people commit, or re-commit, to making organic food choices, and to buying locally and directly from farmers where possible.

In Canada and around the world, organic farmers are at the forefront of building real and lasting solutions to the climate and biodiversity crises. This is a global movement that relies on the support of an informed non-farming public. In this context, individual food choices are more important than ever because they support farmers who are, together, making profound change. At a time of ecological crisis, we are encouraging consumers to take heart from farmers who are already growing food for a better future.

Even consumers who are already making one or more ecological food choices need information to help them continue, and to help them share information with their family and friends. CBAN’s pamphlet says, “your food choices can help protect our environment, support your health, and build a better future for food and farming,” and it describes organic farming. We know this information is necessary because people still ask us if organic is non-genetically modified (GM). They also ask us if organic is sustainable, and if they can trust the organic label. The pamphlet is actually an update of a similar tool launched 10 years ago. People clearly still need this information.

In fact, this information is an important counterpoint to a new highly-organized and well-funded public relations campaign designed to win public trust or “social license” for conventional agriculture practices, including the use of pesticides and genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Coordinated by the Canadian Centre for Food Integrity and Farm & Food Care, the campaign is tracking public opinion and asking farmers to speak up to counter consumer mistrust.

However, this campaign does not change the reality that, as described in “Why Your Food Choices Matter,” most of the food we eat is produced through a long chain of steps in a global system that contributes to the climate crisis, puts harmful toxins into our environment, and removes decision-making from farmers and consumers. This global food system is dominated by a few large companies that control the markets for seeds, pesticides, and other technologies, as well as much of the distribution and sale of food in our communities. But consumers don’t have to surrender to this reality—they can choose an organic path forward, with local farmers.

According to the International Panel on Climate Change, agricultural production contributes approximately 12% of human greenhouse gas emissions. This includes emissions of nitrous oxide from synthetic fertilizers and methane from livestock production. When we add emissions from other related activities in our global food system, such as food production, land-use changes such as clearing forests to make way for farming, manufacturing pesticides and fertilizers, and processing, packaging, and transporting food, this number increases to 21%-37% of all global emissions caused by human activities. Synthetic pesticides and chemical fertilizers are both petrochemical products, made from fossil fuels.

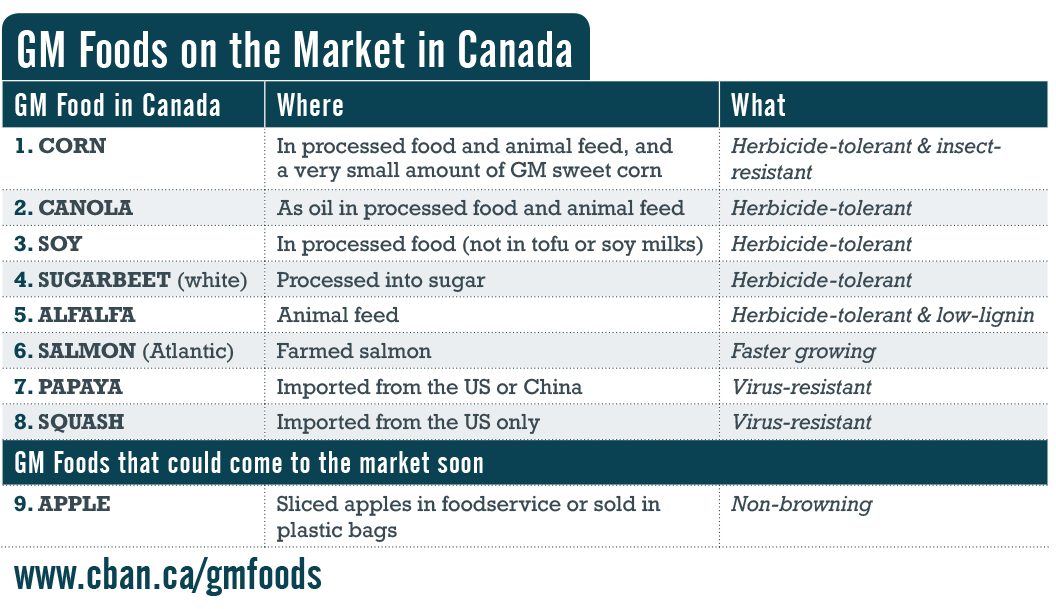

Canadians are increasingly becoming more aware about the use of synthetic pesticides in farming, or at least the use of glyphosate-based herbicides. For many consumers, glyphosate is a concern that is also associated with the use of genetically modified seeds. This connection is correct because almost all the GM seeds sold in Canada are engineered to be herbicide tolerant, and most of these are glyphosate tolerant. CBAN’s research has found that herbicide sales in Canada have increased by 199% since the introduction of GM crops (1994-2016).

However, glyphosate formulations are only one among many different types of synthetic herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides used to produce the majority of food on the market. In fact, the emergence of glyphosate-resistant weeds has meant that companies have started shifting their sales from glyphosate-tolerant GM crops to 2,4-D- and dicamba-tolerant GM crops.

Corporate consolidation is a defining feature of our global food system. Four companies control over half of both the global seed and pesticide markets. These same top companies also control the sales of genetically engineered seeds. For example, Bayer is now the largest seed company, the second largest pesticide company, and the largest seller of genetically engineered seed in the world. Following its acquisition of Monsanto, Bayer owns 33% of the global seed market and 23% of the global pesticides market.

This high level of corporate concentration in seeds and pesticides is unprecedented, and it means higher prices for farmers, fewer choices, and decreased seed diversity. These inputs have environmental costs, and also take money out of farmers’ pockets. In 2018, Canadian farmers spent 94% of their gross farm income on farm inputs. This is why the National Farmers Union (NFU) has just launched a new discussion about how the farm crisis and the climate crisis are linked.

The NFU says, “The solutions to the farm crisis and the climate crisis are largely the same: reduce dependence on high-emission petro-industrial farm inputs, and rely more on ecological cycles, energy from the sun, and the knowledge and wisdom of farm families.” This conversation is in full swing due to a new alliance called Farmers for Climate Solutions, which is creating space for farmers to share stories about climate impacts, practical solutions and policy recommendations.

Organic farming provides a path forward, but encouraging organic consumption alone is not sufficient. This is why CBAN’s pamphlet encourages a range of complementary consumer food choices. For example, we know that small independent food manufacturers and stores are facing pressure in a marketplace dominated by the big grocery chains. Five grocery companies (Loblaw, Sobeys/Safeway, Costco, Metro, and Walmart) control 80% of the food retail market in Canada. This is why we also emphasize the importance of buying directly from farmers, and from local and independent businesses.

Along with all these issues, consumer concern over genetic engineering (genetic modification or GM) is also driving support to organics. New techniques of gene editing are the latest way that genetic engineering is being sold as the future of farming. However, the connection between the two issues of genetic engineering and organics is about more than just an option to buy non-GM via organics.

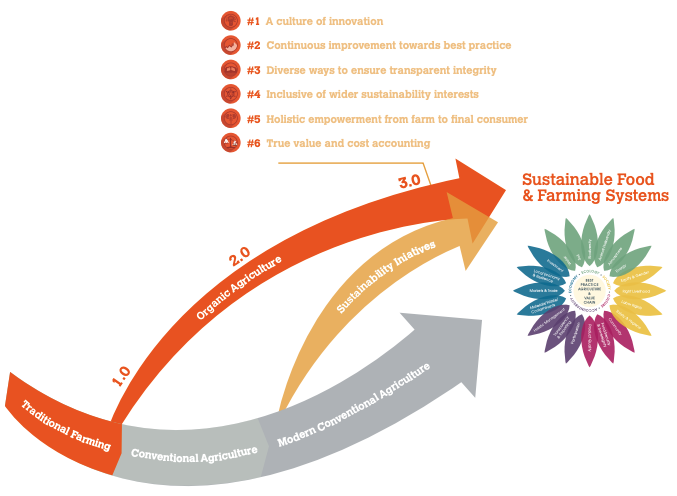

Genetic engineering and organics offer two different visions for farming, and two different visions for problem solving. Organic farmers reject GM seeds and GM animals as unnecessary and risky. Instead, organics values the diversity and bounty that nature already offers, and often replaces such corporate products with natural systems and human labour. This is why emerging and powerful new genetic engineering techniques such as gene editing will fail to provide the solutions needed. The real solutions are in the hands of organic farmers, and it is time to mobilize consumers to more fully support farmers’ work.

You can view the pamphlet “Why Your Food Choices Matter,” along with references for the information, and order your copies at cban.ca/orderpamphlets. You can also contact us at cban.ca/contact or call Lucy at 902.209.4906.

Copies are available free of charge, though your donations to help support printing and postage are gratefully accepted (and tax-deductible).

Lucy Sharratt is the Coordinator of the Canadian Biotechnology Action Network (CBAN). CBAN brings together 16 groups to research, monitor and raise awareness about issues relating to genetic engineering in food and farming. CBAN members include farmer associations, environmental and social justice organizations, and regional coalitions of grassroots groups. CBAN is a project on the shared platform of Tides Canada, a registered charity.