Why Nature’s Path Embraces Real Organic & Regenerative Organic

Arran Stephens, Nature’s Path Founder, and Dag Falck, Nature’s Path Organic Programs Manager

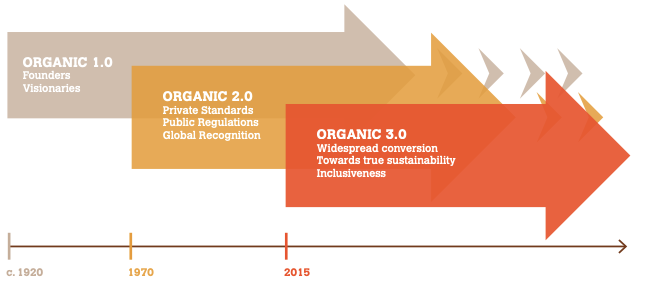

Pioneer organic farmers were the visionaries of their age. Like many other inspired thinkers born before their time, they viewed the ordinary in extraordinary new ways, working quietly and diligently towards an alternate approach, often years or even decades before the general population awaken to the same realizations.

Consider the doctor who was fired from his job in 1847 for suggesting that surgeons wash their hands before operating on a patient. Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis and his new “idea” of practicing basic sanitary procedures has saved millions and millions of lives.

At the center and core of Nature’s Path Foods is the goal of creating an agricultural system that aims towards healing the soil, land, water, air and all of us who rely on these essential and natural elements.

All around the world, people are waking up to the direct connection between how we farm locally and the massive collective impact this has on the stability of the global climate. This awareness has led to a will to do something about it. And we welcome the conversation on how we better reach that goal.

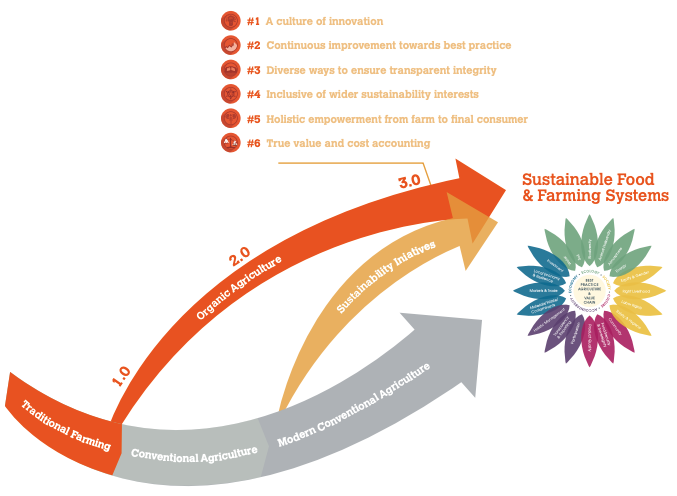

Around the time of the Industrial Revolution, humanity was excited with a “new form” of agriculture that increased yields and reduced backbreaking labor. It was clear that the invention of mechanical tools and chemicals that lent themselves to mass agricultural production of food and fiber was welcomed and celebrated worldwide.

At the same time, there was a handful of visionary individuals spread around the globe who had an awareness of a different sort. They observed how traditional agricultural practices had developed over thousands of years, being vital in support not only to people, but to all living things.

They saw the tiny organisms in the soil, the animals and people living above ground, all working together in cooperation in a way that provided calories and nourishment through the plants growing in the soil. This whole-system-approach is now recognized as having an intrinsic capacity for maintaining and perpetuating a complex balance where all parts co-exist in balance.

We call this system “nature,” which includes supporting the modulated climate on planet earth that makes our existence possible.

As if by some divine decree, this diverse core of individuals across the globe were awakening to this insight about the same time, being mostly unaware that others like themselves were all having the same revelations. The individuals and small groups inspired by this idea often felt isolated, and their efforts to reconnect with Nature as their role-model and teacher was certainly considered as going against the tide. In their experience, the system of cultivating the soil was not seen as having value, and these visionaries were often ridiculed as wanting to return to harsh and barbaric methods.

This was a key period in history where the concept of being “alternative” took hold. Carrying the torch for an idea not embraced by the mainstream society is a hard path with much struggle and little recognition. Especially in the early stages, visionaries are often exposed to ridicule and direct opposition from the mainstream way of doing things.

Imagine the frustration of Dr. Semmelweis, when he met resistance to something as simple as washing hands before surgical procedures. He clearly saw the death toll resulting from not doing so.

Fortunately for us, the visionaries who came before our time were provided with an extra dose of resiliency and energy that allowed them to keep going against all odds. They never gave up and they often did not receive any recognition in their own lifetimes. And the issues that they fought for didn’t see the light of day until generations later.

Organic farming is one of these alternatives.

The early organic farming pioneers bravely blazed the way forward. They lived and died believing in their vision, but never saw any real uptake on any large scale. Years later, organic agriculture started to grow as a movement, and with it, organic food and fiber became available around the world.

Even if organic agriculture is just a drop in the bucket compared to the growth of chemical and industrial monoculture, we have arrived at a moment where the pioneers of the organic movement and their vision for a healthy and truly sustainable way of agriculture are becoming recognized by an ever-growing segment of society. It can no longer be denied that our very survival as a species depends on shifting our current conventional agriculture model towards the kinds of organic practices that nurture and support nature’s wholistic system health. This is the birthing room that today’s Regenerative Agriculture movements have been born in.

Is Nature’s Path excited about regenerating agriculture? You bet!

Yet in the last few decades of false starts and opportunistic profiteering muddying the waters of the soil health movements, we’ve observed label claims like “natural” that have no proper definition, with no standards and no certification or oversight. This has confused consumers and provided a mockery of the soil health movements with deeply authentic goals to improve conditions for all life on earth. The organic movement has always been in front and center of this conversation.

Our highest hopes for the latest movement to hit the scene is that it will drive a sincere and intensely practical revolution for how we care for the thin crust around the earth that feeds all life here. Our thin layer of top soil, and the new movement recognizing its paramount importance has taken on the name of Regenerative Agriculture.

The three key concepts that gave rise to the recent iteration of the regenerative agriculture movement are that:

- Soil which is nurtured to support a largely unseen microbial network will grow healthier plants,

- The plants grown in healthy soil provide healthier nutrition for people and animals, and

- The big “Aha!” realization is that this very same healthy soil actually sequesters enough carbon from the atmosphere to heal our catastrophic global climate disruption.

Nature’s Path Foods is deeply concerned over the disastrous effects of climatic change felt by people in most parts of the world, and vocal with our message that the problem of climate change must be recognized as the most critical issue of our age.

How amazing is our discovery that organic farmers indeed hold the knowledge to reverse a climate calamity? Nature’s perfect mechanism of photosynthesis can draw carbon down out of thin air, and lock it into living soil. By simply taking better care of the soil and nurturing the life that lives below our feet, we can contribute so importantly to the most existential crisis humanity has yet faced.

The life in our soil can hold much more carbon if we only treat it well and allow it to flourish instead of constantly applying practices that diminish its fertility and vitality.

At this point please allow us to make an introduction. Dear regenerative movement: Meet the organic movement.

We have a lot in common and could benefit from sharing ideas and best approaches. The organic movement brings decades of hands-on experience in carrying an unpopular torch and what it takes to keep it burning despite opposition from powerful vested interests.

Our common bond is capturing carbon to reverse climate crisis. Where the divergence happens is in the details of the plan to accomplish this.

There are two main challenges: One is that according to the latest science, there is very little time to make enough of an impact to actually affect the climate— so we need to be in a hurry by necessity. The other is that if the scale of adoption is not massive, then the outcomes won’t be big enough to make a difference.

Reaching large scales of adaption in a hurry is undeniably the key to success. We will even venture to guess that most people with a stake in one or more of the myriads of today’s regenerative initiatives are with us on this assessment so far—that we need to scale up in a hurry.

Here is the point where we face a wide divergence of approaches. Two key strategies to help reverse the climate crisis. If we are to rise above our respective positions in this massive puzzle to save soil, environment, climate and humanity, we will need to find ways to synchronize our efforts. The first logical step in addressing both speed and scale is to tap into everyone’s efforts at the same time.

Our conflict centers around these two opposing theories:

A) That carbon intensifying farming can be achieved by adding practices to any existing form of agricultural system today, including “conventional.” Versus;

B) That even with the best added practices, success cannot be achieved without also addressing the removal of those practices that have the most grievously detrimental effect on the life in the soil.

A is the conventional regenerative movement’s belief, and B is the organic belief. We have to be clear about this and not settle for a compromise where we say we promote carbon capture, while also allowing use of the methods that basically make that intent ineffective.

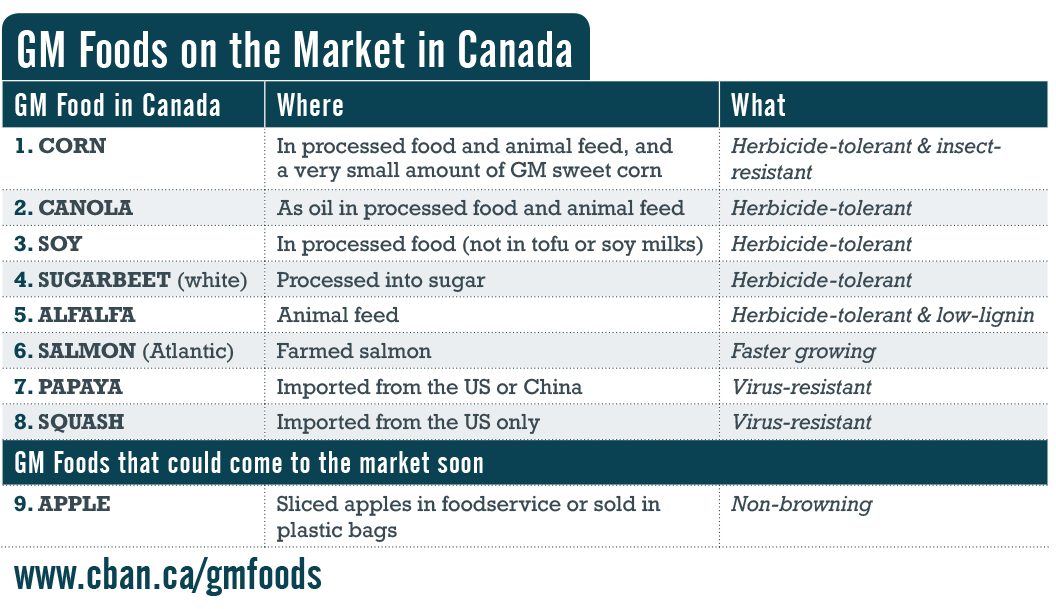

“Regenerative Agriculture” is easily co-opted and used as a form of greenwash and duplicity. Regenerative Organic agriculture does not employ fossil fuel-based synthetic fertilizer, toxic pesticides or GMOs, and agricultural practices cannot be labeled as Regenerative if they are harming people and polluting our planet.

We simply and clearly cannot call it Regenerative Agriculture by introducing a few time-honoured organic practices such as crop rotations, compost and ruminant pasturing into any practice that allows the use of toxic chemicals and GMOs.

Reaching scale quickly cannot be done with clever wording alone. The practices actually must have a positive effect on carbon capture.

We must directly address the applications of agrichemicals that are working counter to actual carbon capture and diligently weed out these practices, while requiring agricultural producers to add regenerative practices. Carbon intensifying farming cannot be achieved by adding practices to today’s conventional systems of heavy reliance on synthetic fossil fuel-based agrichemical inputs that kill the life in the soil, which is responsible for the capturing of carbon.

To meet the goal of scaling-up solutions to the climate crisis, we must evaluate which of two critical practices have the most detrimental effects on the life in the soil:

- Is it the practice of using agrichemicals on the soil to control weeds, disease, and fertility, with the consequences of negatively affecting soil life, or

- Is it the practice of tillage, which addresses weeds, disease, and fertility, but which may expose the soil to baking in the sun, eroding in rains, and the resulting loss of soil life?

We agree that tillage needs to be reduced and be carefully practiced with discretion. But even in its most extreme form, it is not thought to be anywhere near as detrimental as agrichemicals.

The fork in the road where we are standing today looks like this: The south fork is going along without confronting the status quo of industrial agriculture, while adding carbon-capturing practices. The north fork is confronting the status quo, and adding carbon-capturing practices.

As part of our commitment to continue raising food on a compromised planet, we all have to wrestle with these issues and decide which fork in the road we will follow. All we can offer is the suggestion that we all look clearly and dispassionately at the issues. For Nature’s Path, the north fork is the one we choose to take. In our assessment, chemicals have a strong detrimental effect on the ability of our topsoils to capture carbon and do not belong in a food production system in the first place.

Tillage can be moderated. Before agrichemicals, there was no alternative to tillage, and we refuse to believe we’re stuck with putting poisons on our food and fiber-producing fields in order to save our climate. Organic farmers have long proven that food can be produced without chemicals, using some tillage as a tool.

Our hope is that the diverse regenerative agricultural movements will seek to find existing systems that already embody the solutions we disparately need to implement, and deeply study the successes and challenges in these systems to see how they can be scaled up quickly.

Let’s take a closer look at historical examples where sustainable, regenerative practices have been employed over the ages. In Asian wet rice farming, abundant soil fertility has been consistently maintained, producing bountiful harvests on the same plots for over 2,000 years. The greatest input we can add to our farmlands is the wisdom of cultures around the world who have been growing organically for hundreds of generations before chemical agriculture was introduced in the 20th century.

Since the recent invention of “conventional agriculture”, we have been steadily eroding soil fertility and rapidly increasing the destruction of our natural environment— while decreasing the nutritional content of our food.

We should view and treat our soil as a bank containing the present and future wealth of nations. Instead of reinventing the wheel, let’s utilize the momentum already built by the worldwide organic agriculture movement. It has not yet reached the scale we need to solve the climate crisis, but there is no comparable system of agriculture that is as well defined and that has as much success to show.

Let us all join ranks with organic and make it the kind of movement that can change the world on a large scale. With your help, we can get past the tipping point and make the kinds of changes in our food system that we need to survive.

In the end, organic agriculture is really just good farming. It treats natural soil life, insects, animals, people, air, water and earth with integrity. Our support of the Real Organic Project is not a radical move— it’s simply a clear statement for the preservation of integrity in organic.

Together we offer the strong voice needed to stand up against the practices now tearing the fabric of the planet apart. And as the Real Organic Project continues to raise this voice in support of integrity in the face of well-entrenched and well-financed opposition, Nature’s Path hopes that it won’t stand down or give in.

Organic knows what it’s like to be a threat to the world economy’s largest interests. If healthy soil is the solution we need, then the chemicals that kill the life in the soil must be prohibited.

That’s doing, versus promising.

Pioneer, entrepreneur, artist and visionary, Arran Stephen’s organic legacy sprouted more than 50 years ago with just $7, a $1,500 loan and a dream. After opening the first vegetarian restaurant in Canada and the first organic cereal manufacturing facility, he is now leading future generations down a path of organic food and agriculture practices so we may all leave the Earth better than we found it. naturespath.com

Recognized as an expert in the organic industry, Dag Falck has served as Organic Program Manager for Nature’s Path Organic Foods since 2003. Prior to joining the company, he was an organic inspector for 14 years.