The More the Better? Multi-Species vs Single-Species Cover Crops for Carrots

By Frank Larney, Haley Catton, Charles Geddes, Newton Lupway, Tom Forge, Reynald Lemke, and Bobbi Helgason

This article first appeared in Organic Science Canada magazine and is printed here with gratitude.

In recent years, diverse cover crop mixes or ‘cocktails’, which contain as many as 15 different cover crop species, have gained popularity. Are these multi-species cover crop mixes any better than their less sophisticated counterparts (e.g., fall rye or barley/pea)? It’s a complicated system to untangle. Our early data suggests that the multi-species mixes can foster more active soil life, but that they could also have impacts on the following crop: they caused more forked carrots, which decreases profit. We also looked closely at how weeds in the cover crops affected soil fertility. Spoiler alert, they may be helping…

Cover crops can provide many benefits including enhanced soil organic matter and soil health, nitrogen retention, weed suppression, soil moisture conservation and, as a result of these, higher subsequent crop yields. Cover crops can be grown in the main season (replacing a cash crop in rotation) or seeded in fall to protect the soil from wind and water erosion throughout winter and early spring. In our study funded by the Organic Science Cluster, we compared how different cover crops impacted the soil, pests, and the following crop.

Our research team collaborated with Howard and Cornelius Leffers who run an irrigated organic farm near Coaldale, Alberta. They specialize in carrots and red beets for restaurants, farmers’ markets and organic grocery stores, and they also grow alfalfa, winter wheat and dry beans. We evaluated seven cover crop treatments ahead of carrots. We have completed two cycles of the two-year cover crop–carrot rotation (Cycle 1: 2018 & 2019, Cycle 2: 2019 & 2020), with a third cycle (2021 & 2022) currently underway. Cover crops were established in June during the first year of each cycle as follows:

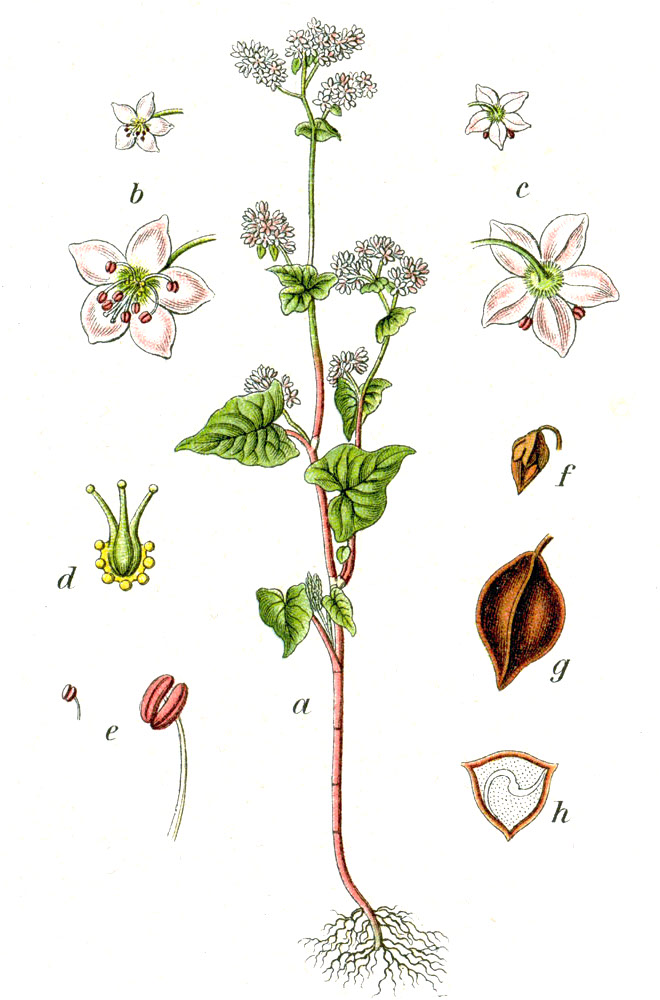

Buckwheat;

- Faba bean;

- Brassica (white + brown mustard);

- Mix*;

- Mix* followed by barley which grew until the first killing frost;

- Mix* followed by winter wheat which survived the winter, regrew in early spring, then was terminated by tillage; and

- Control (no cover crop, weeds allowed to grow).

- *Mixture of five legumes, four grasses, two brassicas, flax, phacelia, safflower, and buckwheat (15 species in total)

In August, all treatments and the control were incorporated into the soil by disking. The control and treatments 1-4 were left unplanted over the winter; weeds were allowed to grow. Treatments 5 and 6 were seeded to other cover crops. In the second year of each cycle, carrots were planted in June and harvested in the fall. We took cover crop and weed biomass samples just before disking in August of the first year of each cycle. We measured the carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) concentrations of the cover crops, as well as the main weed species. In 2018, the multi-species, brassica, and buckwheat cover crops were more competitive with weeds. The faba bean cover crop was not competitive with weeds and had the same amount of weeds (by weight) as the control treatment.

Weeds can be a troublesome part of organic systems. In this case, we wanted to see if they were redeeming themselves as part of the cover crop, or in the case of the control treatment, by taking the place of a seeded cover crop. Weeds are no different from any other plant: they take up soil nutrients and when they break down, they put carbon (including organic matter), nitrogen, and other nutrients back into the soil. As long as annual weeds don’t go to seed, maybe they are making a useful contribution to soil health, similar to a seeded cover crop.

Since weeds were incorporated into the soil in August along with the seeded cover, the less-competitive faba bean treatment and the weedy control actually returned more total carbon to the soil (average, 2220 kg/ha C) due to greater weed biomass (weed “yield”) than buckwheat, brassica or the multi-species mixture (850–1330 kg/ha C). Moreover, being a nitrogen-fixing legume, the faba bean cover crop (including its weeds) returned the most nitrogen to the soil at 99 kg/ha N. After the carrot harvest, our team rated carrots into Grade A (visually appealing with no deformities: ideal for restaurants, farmers’ markets, and organic grocery stores) and Grade B (downgraded due to wireworm damage, forking, scarring or misshaping: suitable for juicing only). Grade B carrots are worth about one third of Grade A carrots.

Despite the differences we measured in the C and N contributions of the cover crops and the weeds, it wasn’t enough to affect the carrot yields. In 2019, Grade A carrot yield was statistically the same with all the cover crop options. For soil health, the multi-species mixture had more microbial activity than either brassica or buckwheat cover crops (this is based on microbial biomass C – an index of microbial mass – and permanganate oxidizable C – the active or easily-decomposable C). However, a possible downside of the multi-species mix showed up when we looked at the following carrot crop. In 2019, treatments 4, 5 and 6 resulted in a greater proportion of the Grade B category, including forked carrots. Forking and misshaping are caused by many reasons, including soil compaction, weed interference, and insect or nematode feeding on root growing tips.

We also looked at the value of fall-seeded cover crops (Treatments 5 and 6) and their impact on wireworm and nematodes. These pests might actually be helped by cover crops; they appear to have greater survival during the winter season when living roots are present. But having winter cover may lead to better carrot yields, too: in 2020, total carrot yields (Grades A and B) were 10% higher after the fall-seeded cover crops when compared to the spring – seeded brassica cover crop, which led to the lowest yielding carrots. So far, we haven’t seen any effect of the different cover crop treatments on root lesion nematode populations, but the fall-season cover crops led to a small increase in wireworm damage on the carrots (this only showed up in 2019). More soil analyses and the results from the 2021-22 season are still to come. The additional information will help us tease out the pros and cons of multi-species vs single-species cover crops for irrigated organic carrots.

To learn more about OSC3 Activity 8, please visit

The Organic Science Cluster 3 is led by the Organic Federation of Canada in collaboration with the Organic Agriculture Centre of Canada at Dalhousie University, and is supported by the AgriScience Program under Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Canadian Agricultural Partnership (an investment by federal, provincial and territorial governments) and over 70 partners from the agricultural community.

Feature image: Left to right: Charles Geddes (Weed Ecology & Cropping Systems, AAFC-Lethbridge); Howard Leffers (farmer-collaborator, Coaldale, AB); and James Hawkins (visiting Nuffield scholar, Neuarpurr, Victoria, Australia) in the 15-species cover crop, August 7, 2018. Credit: Frank Larney.