Where Scientists and Farmers Converge: The Summerland Research and Development Centre

By Annelise Grube-Cavers

This fall, as part of the BC Organic Conference, attendees had the opportunity to tour the Summerland Research and Development Centre. It was quite exciting to wander around the 80s era research center perched on a hill above Okanagan Lake (if you get excited about that kind of thing, of course, and I venture that farmers do).

This tour was supported by the BC Climate Agri-Solutions Fund (BCCAF). BCCAF provides funding to support producers in adopting beneficial management practices (BMPs) in three specific areas: nitrogen management, cover cropping and rotational grazing. In addition, the program funds activities to support the adoption of BMPs—such as this tour!

The centre really does bring to mind desert landscapes from images of NASA space stations or bomb testing zones. The building is a bit of a bunker, architecturally speaking, and the surrounding terrain is the typical dry scrubby grassland of the Okanagan. But instead of launching rockets, this center is the jumping-off point for the research needs of a slower-moving science—one that regularly takes generations to make it to the mainstream: the genetic diversity and breeding of tree fruits. There are other fields of research as well (30 different programs in total!), including cover cropping and intercropping studies, as well as the testing and monitoring of biological controls, but the longest running research trials are all tree-fruit-based.

We were greeted upon entering the facility by Knowledge and Technology Transfer program specialist and biologist, Jesse MacDonald. He offered to show us around the gardens and field areas after our more formal facility tour. The offer was extended “even if only a couple of people were interested.” Hours later our entire group of some 40-odd agriculturalists disbanded as the sun went down, following a thorough introduction to several varieties of cherry (all named starting with S since they were developed there in Summerland).

The research centre is a fascinating space—we witnessed presentations on field trials as well as scholarly research. I learned, for the first time, about lentils being used as an in-row cover crop in vineyards and orchards (later in the conference we heard from Gene Covert that he had experienced reduced powdery mildew in the areas of his vineyard where lentils had been planted).

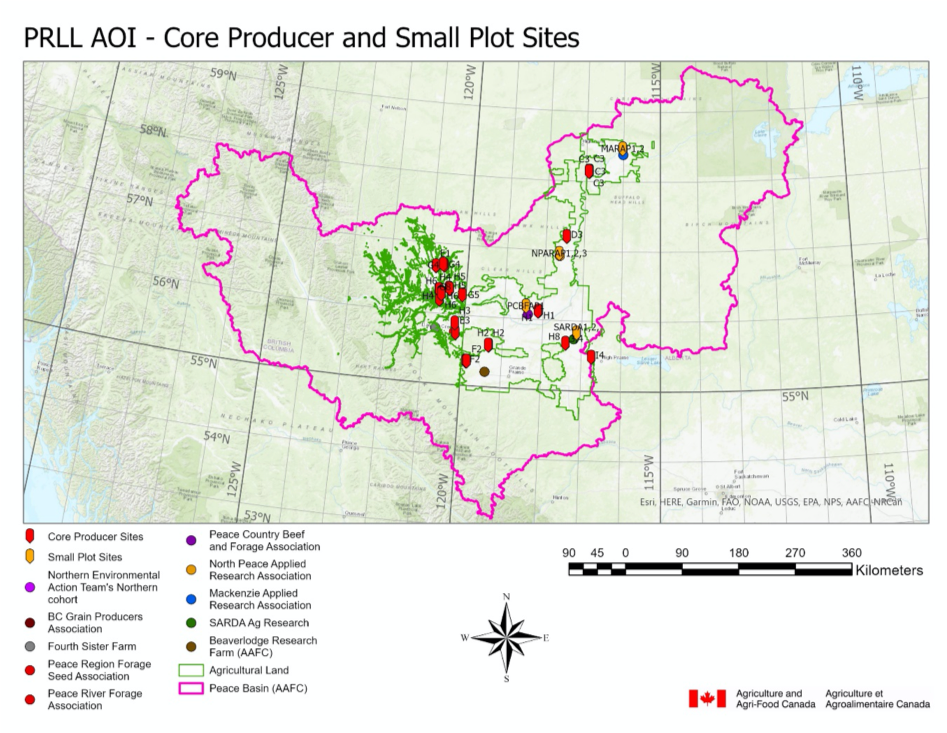

I only wish that there were more field research centres looking at other diverse crops. Jesse noted that there had previously been livestock and field crop components at the research centre, but that tree fruits had been the primary focus, including the breeding program had started in the 1930s. Now it seems that forage and animal feed research happens in Agassiz, field crops are largely studied in Ontario, and vineyard and tree fruit research dominate at the Summerland Research Centre, though more research centres are sprinkled across the country. Research priorities are sometimes industry driven, but government funding is almost entirely determined by national priorities, which don’t always capture the research needs of the smallest and most diverse systems.

Molly Thurston, a tree fruit and cherry grower with orchards in Lake Country and Creston, notes that in her experience the impact and success of the Research Centre has had one caveat: access. In other words, can farmers reach scientists, and is the research coming from the centre readily available to producers?

Our tour felt like a step to improving accessibility going forward, with many more opportunities to share the research in the future. There is fascinating research being done, and ensuring that the people who need to utilize the practices under research can learn about them, question them them, and implement them on-farm, is essential to making that research worthwhile. When it comes to adaptation for climate change, the push to bring research to producers is even more expedient.

For participant Sarah Martel, the biological and pest control aspects of the tour were the most applicable and interesting. “It’s great that there is some research being done that applies to organic growers,” she said. The rigorous testing and assessments of possible controls, and past examples of biological control gone wrong, reinforced the importance of treating our natural ecosystems with respect.

Within the system of nationally-selected priorities, there is apparently also room for innovation and collaboration. A new Indigenous garden at the Summerland Research Centre hosts stsǝrsɬmix (oregon grape) and soopalallie among many other native species, and is centered around a large Ponderosa pine. Originally, the goal was to have this garden accessible to the public, but it ended up being planted behind a tall locked gate. Perhaps the garden will spill down beyond the gate and the riches of research and knowledge will become more accessible soon.

For more information on how to learn from researchers at the centre, or to read about possibilities for on-farm collaborations and research visit: bit.ly/3OEyIhS

Annelise raises pasture-raised livestock with her partner Steve at Fresh Valley Farms on unceded Secwepemc territory outside of Armstrong, BC. They have two farm kids and have just started an adventure in agri-tourism because life wasn’t busy enough…

This project was supported by the BC Climate Agri-Solutions Fund; delivered by the Investment Agriculture Foundation. Funding for the BC Climate Agri-Solutions Fund was provided by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada through the Agricultural Climate Solutions – On-Farm Climate Action Fund.

Featured image: Grapes ripe for harvest at Kalala Estate Winery. Credit: Maylies Lang.