Animal Behaviour and Stockmanship

Or: How to Never Have to Chase Sheep in Circles Around a Paddock Ever Again!

Sara Sutherland

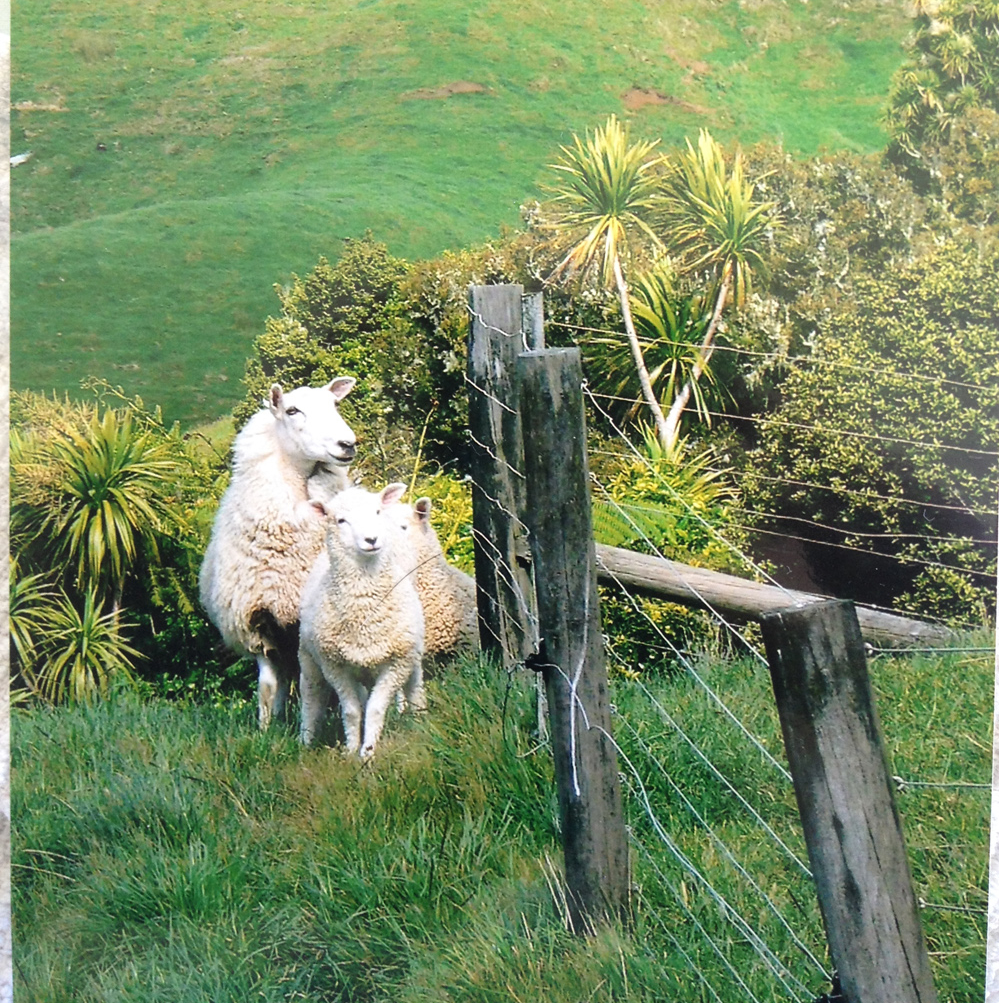

Many people believe that sheep are stupid. Even people who have never worked with sheep tend to think that sheep are stupid. Broadly speaking, there are two categories of things that sheep do that make people think they are stupid. Firstly, sheep mob together, follow each other, follow the bellwether up the steps to the slaughterhouse, and generally show a lack of independent thought. Secondly, sheep scatter, run the wrong way, get out of fences, and when you get almost all the sheep into the pen and close the gate one will inevitably spin around and run out just before you get the gate closed. (If you think about it, this isn’t fair—dumb if you do and dumb if you don’t!)

When you work closely with sheep, you begin to realize that they also show signs of intelligence. Sheep will watch when you fix a hole in the fence, then go and check if it’s really fixed. Sheep will teach each other to get into a feeder that is supposed to only let lambs eat. A researcher in the UK, Keith Kendrick, studied facial recognition in sheep. Sheep would push the button beside the photograph of a sheep they knew, a flockmate, instead of a sheep they didn’t know. They could recognize over 30 individuals, and remember for at least three years after the last time they had seen the animal in the photograph!

So if sheep are so intelligent, if they have this capacity for recognition and learning and memory, why do they do stupid things?

Sheep don’t have a lot of natural defences. They don’t have sharp teeth, they don’t have long fangs, they don’t shoot lasers from their eyes (fortunately). Because they are prey animals, they are highly motivated to avoid being eaten. The most dominant sheep in a flock is not the leader, the most dominant sheep is in the middle where it is safest. When there is a group of animals of similar size running past each other, it is very difficult for the predator to focus on one individual. If you have ever tried to catch an individual sheep out of a flock, you know that you really need to stay focused on one individual in order to be successful. Statistically, a sheep in a flock of twelve is less likely to be eaten than a sheep in a flock of three. So sticking together, circling, and following each other are not caused by stupidity. In fact, they show a sophisticated understanding of statistics!

What about when sheep scatter and run the wrong way? Every animal has a “personal space bubble” or “flight zone”. When you step into their flight zone, they move away. The size of the flight zone varies. The biggest factor affecting the size of the flight zone is habituation—how used to you the animals are. To reduce the size of the flight zone, habituate your sheep to your presence. They are intelligent enough that if you walk through their paddock regularly they will recognize you and become gradually less wary of you. If you step into their flight zone behind their shoulder, they will move forwards, in front of their shoulder they will stop or turn around. Always be aware of where you are in relation to the animal. Why does one sheep spin around and run away from the flock when you go to shut the gate? She is motivated to be close to the other sheep until you step into her flight zone, then she is highly motivated to gap it. So take your time, let them all move into the pen, then watch the outside sheep and move into her flight zone behind her shoulder as you slowly shut the gate.

There are between breed and within breed variations in the size of the flight zone. There are no naturally “bad” breeds though—animals of any breed will habituate with regular calm handling. Animals that are stressed or in pain will have a larger flight zone. You should keep this in mind and not expect them to react the same way they normally do when something is wrong. Sheep in a smaller group will be more reactive than sheep in a larger group. They type of stimulus will also affect the size of the flight zone. The most effective stimulus for getting sheep to move is something that is novel—something that they haven’t been exposed to before. It doesn’t need to be especially loud or annoying, even a plastic bag on the end of a stick works well until they get used to it.

If animals get really stressed, it takes them a period of time to go back to behaving normally. Think about the last time you had a near miss in traffic, and how long it took for your heart rate to go back to normal! So if things really turn to custard, walk away and let them relax and come back 20-30 minutes later (providing it is safe to do so).

Unlike dogs, sheep predominantly use vision to experience their environment. Sheep do see differently than we do. They see things moving on the horizon better than we do, but large things close-up not as well. They see greens and yellows better than we do, but reds and blues not as well (so don’t use them to help you chose your wallpaper). They see vertical bars on a gate better than horizontal ones—if your sheep keep banging into the gate maybe they don’t see it well.

When you are designing handling facilities for sheep and cattle, whether it is a set of pens and races or just a couple of gates in the corner of the paddock, use these principles to make it easy for the animals to do what you want them to do. Set it up so that they can circle and stay close together. Make sure they can see where they are going; for example, make sure that you are not running a race into a blank wall. When you are moving animals, use their flight zone and balance point. Don’t chase them around in circles—you will only make them stressed. Habituate them to a handling facility by running them into it a couple of times before you do anything stressful or painful to them in there. Look through a race from the sheep or cow’s eye level to try and spot anything likely to make them baulk as they run through. Sudden changes from light to dark, shadows, reflections, and hanging flappy things are common issues that we might not notice that make sheep or cattle not want to run.

Why is this important? Firstly, if you are set up to use the animal’s natural behaviours instead of working against them you will get the job done more quickly. Secondly, you will get the job done more safely. People can get injured by sheep and cattle, and if you are stressed because you aren’t well set up to handle animals you are more likely to do something dangerous like roll the motorbike or tell your partner you don’t like their cooking. Thirdly, stress makes animals more likely to get diseases. So if you are set up to work with the animal’s natural behaviour instead of against it, you will find your animals are healthier, you are safer, the work is done more quickly and more easily, and you might find that actually sheep aren’t as stupid as you thought!

Sara Sutherland is a large animal vet in the North Island of New Zealand, specializing in sheep. She’s from a large family farm in Quebec with meat and dairy sheep, and currently not only provides vet services for farms from 20-2,000 head of sheep but also conducts research and hosts workshops on management for farms in the region.

Photos: Sara Sutherland