Organic Stories: Crannóg Ales, Secwepemculecw (Sorrento) BC

Rest is Key to Innovate (and Survive a Pandemic)

Michelle Tsutsumi and Rebecca Kneen

Starting this piece during the onset of COVID-19 in BC created a curious opening for Rebecca and I to delve deeply into what improvement means for organics (both of us speaking from a smaller scale perspective, with the need to hear more from our larger scale colleagues). The presence of a pandemic spotlighted the precarity of our food system, the inequity within it, and the need to shift the system. We had no idea where things would be two weeks later.

Over the span of two weeks, there were significant pivots so that farmers and processors could continue to get their food and beverages to people (with a pinch of panic as the future of farmers’ markets became more uncertain). After several communities closed their farmers’ markets (or contemplated closing them), it was a relief to hear the provincial government declare farmers’ markets as an essential service on March 26.

Throughout the two weeks, I have witnessed the (direct market) organic community coming together to mobilize online platforms, change their CSA delivery methods, and coordinate new distribution channels, all from a foundational value of helping each other in hopes that we will all be okay through this. This deserves acknowledgement as a core part of organics that needs no improvement. The organic movement and community formed from a belief in interconnectivity and this will continue to serve us well as we adapt to a world, a way of being, that could be permanently altered by COVID-19.

I am honoured to profile Rebecca Kneen in this issue to discuss how she, Brian MacIsaac, and Crannóg Ales have been improving their practices in ways that “extend deeply rather than extend widely.” Crannóg Ales is celebrating 20 years this year (let’s all raise a glass in congratulations to them!), so there is much to reflect on in terms of where they have been extending deeply. It is important to keep in mind that there is a long history of involvement with the North Okanagan Organic Association, COABC, and the Organic Federation of Canada, so Rebecca can also speak to what she has witnessed in terms of improvements in organics over time.

Let’s set the stage. Picture this interview taking place on our front south-facing porch (somewhat socially distanced), warmed by the afternoon sun, with Dropkick Murphys playing a spirit-raising St. Paddy’s Day gig on YouTube in the background. Even with a pandemic looming, it was a dream way to spend an early spring afternoon.

Where have you seen the greatest change in terms of improved processes at Crannóg Ales?

It took the first 10 years to get to know the land, mostly based on theory, and the next 10 years figuring out what that means with practices on the land. Coming to land as an adult means that a lot of observation is occluded, so it was a lot of trying stuff and then trying new stuff. In the beginning, our practices were what was financially viable, which equalled “the hard way.” Twenty years later, we are better rested, which leads to better thinking. One of our key principles has always been to limit our market expansion to fit the ecological carrying capacity of our land. Because of this, we have been forced to extend deeply rather than extend widely.

What does extending deeply mean to you?

Finding efficiencies and working in increased harmony with the land, letting permaculture principles guide us and making do with less in all ways. There is a balance point in having a growth cap, because the question remains about what scale the brewery, in particular, needs to be at to make a sufficient amount to take care of and support employees. One way we do this is providing extended health care to employees. Another way is to intermingle the farm with the brewery to supply good food for employees.

Extending deeply also interconnects with the way we are being in, and understanding, our relationships to land, water, workers, wild things, the whole around us. Are our relationships exploitative or mutually beneficial? We have been deepening relationships in terms of responsible stewardship, which sees (non-hierarchical) interrelationships rather than partaking in caretaking behaviours, which can involve power dynamics or someone making decisions for someone else.

How else does seeing things as being interrelated play a role in how you have deepened your way of being in the world?

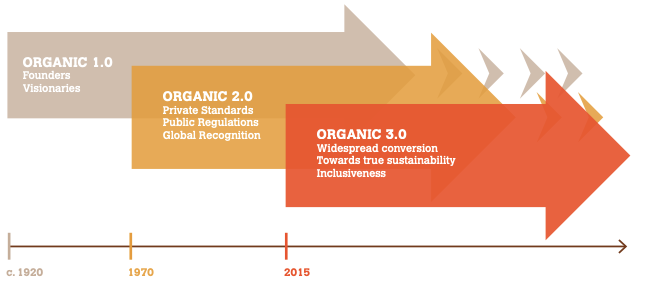

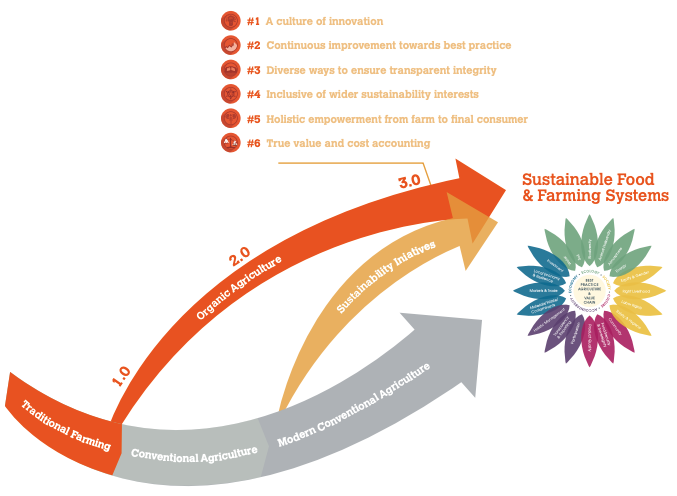

Looking at things in terms of relationships has helped us to see a responsibility to, rather than for, employees. Interrelationships also seem to be part of organics as a movement, which, 20 years ago, focused on social and agricultural change. Making a living was a given, it wasn’t the goal. A shift in emphasis from an organic movement to an organic industry means that we are losing our ethical and ecological focus, which threatens the ability of our robust standards to withstand a strong push from industry toward non-organic practices (similar to mission drift in the nonprofit world, shifting to an organic industry could lead to practice drift).

The way we manage certification is also being lost as the organic movement shifts to that of an industry. This has a large impact on regional or community-based certification (which is still an unusual model, but with increasing membership, interestingly enough), because they are seen as being less valid and less valuable than Canada Organic Regime (COR) certification bodies. In my view, farmer-to-farmer certification review leads to deeper relationships, better understanding and communication, and is just as strict as third-party certification. That being said, people are craving community, which is something the regional certification bodies do well (and also aligns with organics as a movement).

How do you see reconnecting with social change as part of organics extending deeply?

The organic community has long been taking responsibility, where other sectors have been outsourcing or offloading responsibilities. For example, organics has been a leader in terms of traceability standards, responsible packaging and reducing packaging waste, and emphasizing the need for social justice. Social justice becomes an issue of scale when looking at employment. If employment potential is increased, so does the potential for exploitation. Our identity as stewards, as well as values of social justice and fairness, have been grounded in the organic standards, and we are working on deepening these areas nationally right now. With most of BC being on unceded territories, there is an opportunity to deepen our organic perspective on social justice in terms of land and land ownership.

What are ‘next steps’ that you see as being important for social justice in organics?

Listening. And trust. These both entail a worldview or paradigm shift that is reliant on relationships. Reflecting on organics with a social justice lens will challenge our notions of ownership and relations to land. It will be an uncomfortable (but necessary) exercise in questioning our understanding of security and access to tenure. It will require us to work through assumptions and tensions, and let new ideas percolate. Here is an interesting thought exercise: if you hold debt or a mortgage, you don’t truly own the land. Do you really care if the owner is the bank or your Indigenous neighbour? If you do care, this is an opportunity to delve more deeply into the reasons why this matters (and to examine the paradigms of individualism, capitalism, and systemic racism which live in our brains).

After allowing this conversation to percolate and settle, it was interesting to note that what was being named as innovative and improving practices at Crannóg Ales are ancient practices that have been, and continue to be, carried out by Indigenous people and traditional sustainable farmers. These practices are seen in subsistence living through hunting, fishing, gardening, and harvesting medicines. Principled practices of observing and knowing the land, not seeing oneself as an owner of the land, tending to relationships, recognizing interconnectivity, being mindful of scale, and stewardship have been part of Indigenous ways of knowing and being for millenia.

Identifying social justice as being important to organics ties in with the need to stop erasing Indigenous ways of being from the land where we grow and prepare food, including access to this land. If any group or community can do it, it is the organic movement that can start to see the areas where Indigenous food sovereignty and organic agriculture align. In the face of uncertain, and changing, times due to COVID-19, we will need to recognize interconnectivity and help each other more than ever. It is easy enough to remember that what joins us together is the soil, so we can start there as our common ground.

“The soil is the great connector of lives, the source and destination of all. It is the healer and restorer and resurrector, by which disease passes into health, age into youth, death into life. Without proper care for it we can have no community, because without proper care for it we can have no life.” ~ Wendell Berry, The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture.

Resources to Explore Further:

Indigenous Principles of Just Transition

Opinion: Fairness in Organic Agriculture by Anne Macey (2018)

Reviving Social Justice in Sustainable and Organic Agriculture by Elizabeth Henderson (2012)

Food Sovereignty: Indigenous Food, Land and Heritage by Dawn Morrison

Working Group on Indigenous Food Sovereignty

Michelle Tsutsumi is a mid-life switcher to organic farming. She is grateful to have learned from the Hettler’s at Pilgrims’ Produce in Armstrong and has been at Golden Ears Farm in Secwepemculecw (Chase) since 2014. Michelle is also an organizer and communicator, with an eye for process and a passion for systems thinking.