Sparkly Eyes, Grit, and Land Access

New Organic Farmers on Leased Land

Tessa Wetherill

Spring on an organic produce farm looks like baby greens, tiny radishes, overflowing seedling greenhouses, and freshly turned soil. Everything feels precious and new and brimming with possibility. Touring around Loveland Acres in Salmon Arm with farmers Robin and Maylene, those feelings were especially palpable and poignant since it’s their first season on the land. They’ve had a long journey getting here, one filled with familiar challenges and dreams. The other familiar things these farmers have are sparkly eyes and grit, ineffable qualities that go a long way in agriculture.As a farm business, Loveland Acres’ main goal is to provide high quality organic food for as many months of the year as possible. Robin and Maylene have been personally committed to eating as locally and seasonally as possible for many years and have identified a gap, often referred to as the hunger gap, in the availability of local produce in the region.

“We want to help promote the Eat Local message all year round,” says Maylene. Which is why their next big project is to purchase and convert a shipping container into a commercial kitchen, an investment that will give them a place to process their produce, dry peppers, can tomatoes, and make pickles.

In discussing this next step in their business plan, Maylene points out that “no one talks about the money when starting a small farm.” She makes a good point. Even with all their sweat labour, these new farmers have invested a huge amount of money that they saved over a long time of working two jobs each into infrastructure, systems, and set up. They have poly tunnels, seedling greenhouses, storage spaces, and a very impressive irrigation system—all necessary to launch into marketing their products this season. The next step in building towards their goal of providing local food 12 months a year will take more capital than they have available right now, but seeing what these farmers have done in a couple years, I have no doubt they will make it happen.

In 2014, Robin and Maylene both left their professional careers in publishing and printing to pursue a siren song towards sustainable organic agriculture and a better quality of life. In her former life in Toronto, Maylene describes her experience with insomnia and a feeling of unease with the constant race and pace of the city and industry she worked in. When Maylene is asked what she loves most about farming, the answer is easy: mental space. Thinking about whatever she chooses all day long, rather than the 300 emails in her inbox. Contemplative, diverse, connected labour. That said, they both admit to having the occasional nightmare about their greenhouse flying away and that time they missed the window on flame weeding carrots!

Robin and Maylene met interning on an organic farm in Ontario. They fell in love with each other and the land and made a life-altering decision. Being in that environment and working in sync with the processes of nature, they both immediately began feeling healthier and sleeping better. They were learning that this was the life they were called to. They spent the next four years working and volunteering on farms across Canada and eventually found full-time employment working on a third-generation family-owned orchard in the Okanagan.

“For any aspiring farmer, working in agriculture is essential. It is the best way to learn and get hands-on experience. The only catch is that wages in agriculture are prohibitively low, which makes the prospect of land ownership, especially in the Okanagan, pretty unrealistic,” says Maylene. “With the average agricultural wage hovering around $14 an hour and the average price per acre of land in the Okanagan sitting at about $100,000, it’s not hard to see that land ownership is essentially out of the question for most agricultural workers.”

The high cost of land was the biggest hurdle they faced. Starting their new farm business on leased land was the only viable option for them, which is how they ended up connecting with the B.C. Land Matching Program (BCLMP) and with me, the land matcher for the Okanagan region.

Loveland Acres is one of 78 matches the BCLMP has supported on over 4,600 acres across the province since launching in Metro Vancouver in 2016 and expanding province-wide in 2018. The BCLMP provides land matching and business support services to new and established farmers looking for land to start or grow their farm business, as well as landowners interested in finding someone to farm their land. The benefits of land matching are hands-on support services to help new farmers and landowners evaluate opportunities, access resources, and ultimately find a land match partner. The program aims to address a lack of affordable farmland as a significant barrier for farmers entering the agricultural industry. The BCLMP is delivered by Young Agrarians, a farmer to farmer resource network, and is funded by the Province of British Columbia, with support from Columbia Basin Trust, Cowichan Valley Regional District, Real Estate Foundation of B.C., Bullitt Foundation, and Patagonia.

After registering for the BCLMP, we worked together to refine their focus on what attributes Robin and Maylene were looking for in a piece of land, taking the guesswork out of the leasing process and then connecting them with interested landowners.

“The BCLMP is so much more than a program that links landowners and land seekers. They helped us negotiate a stable and secure land lease, provided advice and access to a lawyer to look over our agreement, and connected us with their business mentorship program,” says Maylene. “If Tessa hadn’t reached out to us, we’d probably still be unsuccessfully trying to convince bankers and mortgage brokers that we weren’t crazy, and that, yes, you could make a living growing vegetables on two acres of land, with only a walk-behind tractor and a few simple pieces of equipment.”

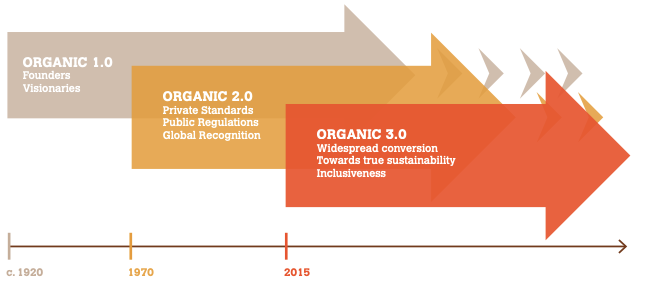

Robin and Maylene knew from the beginning that organic certification was a priority for them, so when they were introduced to landowners Dag and Elina Falck, who own the land on which Loveland Acres has made their home, there was an instant spark of connection through their shared values.

Besides wanting to give their customers a guarantee that the food they produced was being done in a way that met the highest criteria for environmental sustainability, they have also felt the support of a community of fellow organic growers in the region. The pair emphasized the importance of being connected to a group of people who understand what they are going through, are available to answer questions, and generally help alleviate the feeling of being alone in a tough industry. On one particularly bad week, filled with unfortunate life events, including a car breaking down and other irritations, they recalled attending the annual general meeting for the North Okanagan Organic Association (NOOA). Just being in a room with other organic growers gave them the encouragement they needed to push through and keep going.

The willingness these farmers have in engaging with the community and accessing all possible resources to support their dreams has been instrumental in moving them into the exciting place of possibility they are at now. When I asked, what’s the most exciting thing for you right now, they responded by loading me up with freshly-harvested arugula and French Breakfast radishes, which I ate in handfuls on the way home.

Land matchers love being able to help farmers achieve secure access to land to start or expand their businesses, and to help farmland owners enjoy the benefits of agriculture of all kinds on their land. Farmers, get in touch to start a conversation about leasing land for your operation! Landowners, reach out to the BCLMP to help a farmer access land, whether you have hundreds of acres of farmland, or a small urban plot. There are so many growers looking for spaces to produce food across the province, and your land might just be the perfect fit.

Send an email to land@youngagrarians.org and a land matcher will get in touch to learn more about your needs and vision and help you get on your way to making a match.

The B.C. Land Matching Program is funded by the Province of British Columbia, with support from Columbia Basin Trust, Cowichan Valley Regional District, Real Estate Foundation of B.C., Bullitt Foundation, and Patagonia.

Tessa Wetherill farmed full-time and with all her heart for 11 years, first in Vancouver and then the North Okanagan, before joining the Young Agrarians team as the BCLMP’s Okanagan Land Matcher. She loves all things that grow—plants, people, and communities—and what really lights her up are relationships and collaborations that form strong, diverse human ecosystems.

Feature image: Robin and Maylene with starts. Credit: Tessa Wetherill