Biodynamic Farm Story: What Steiner Said

Anna Helmer

I exhibit a strong spring Biodynamic practice. I have all the time in the world for stirring BD 500, tending to compost piles, and dutifully attempting to follow the planting calendar. In the summer things will likely slide, and the fall is very Biodynamically weak for me. Winter comes and at that point it’s out of my hands as that’s when the influence of the distant planets of the cosmos takes effect in the soil. For real.

But that is neither here nor there, for the purposes of spring. Don’t get hung up on that. What’s important now is that this spring I have already vacuumed the farm truck and washed it twice. I am well on my way to cleaning up the shop and tidying the upstairs of the barn. And I have not lost my interest in learning more about Biodynamic farming.

A couple of earnest, active, and idealistic springs have passed since I decided to develop a more learned and deliberate approach to Biodynamic farming. Prior to that, I had been a willing, but not a very wondering, participant in our farm’s practice. I would have happily kept going like that, but my inability to articulate even the basic concepts was undeniably denting my preferred image as a modern, hip organic potato farmer.

Anna, what is Biodynamic farming? Anna of yester-spring: uh, well, you know how the moon and planets and stuff are there…and the soil is important…you have to look after the soil…and make good soil in compost. It’s sort of homeopathy for the soil. Beyond organics.

You see the problem.

Biodynamically-woke Anna: agriculture involves taking crops off the land and is therefore inherently exploitive. A Biodynamic grower knows this and works to replenish and strengthen the life and energy of the soil so that the crops continue to be imbued with taste and vitality.

Oh well, then. That explains that.

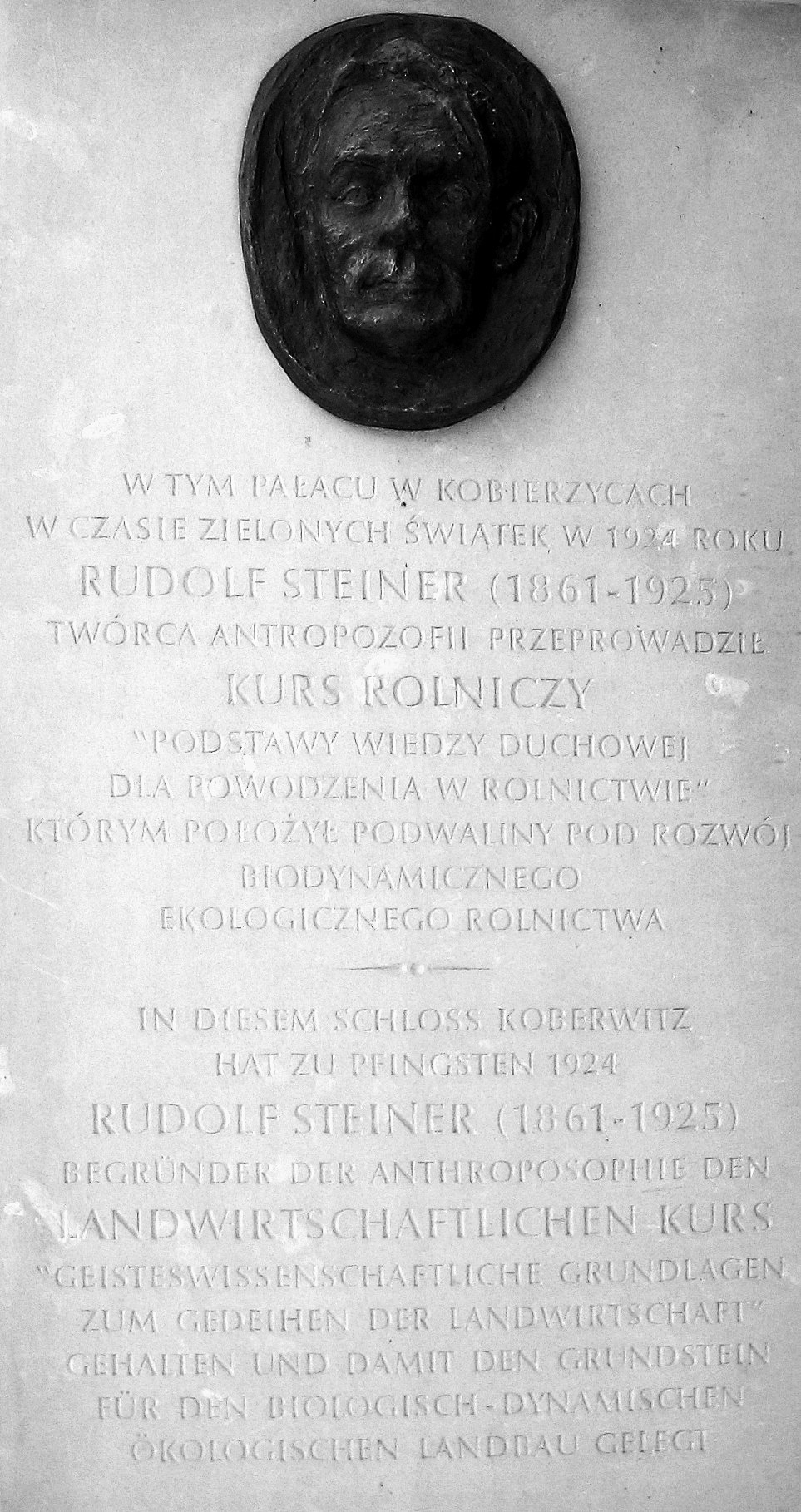

I did not make this up, of course. It is in the lectures, buried deep in Lecture 5. Finally, after countless readings, I have picked up on what Steiner was putting down. If you ask me, he should have led with this idea, rather than launching Lecture 1 with a description of the relative effects of cosmic energy on plants, animals, and humans.

The thing is, though, he didn’t. He died only a year after delivering these lectures and he may have known he was mortally ill at the conference. There may in fact have been a sense of urgency to his delivery. So, he probably started exactly where he meant to start and finding a powerful mission statement in Lecture 5 does not absolve me from figuring out what he is talking about leading up to that point. For now, however, I am agog with dawning comprehension.

Now. You will point out to me that regenerative farming is all about replacing in the soil what has been used, and what’s so special about Steiner saying it? Well, I guess that would be the compost preparations he describes. They are special.

Steiner is not insisting that farmers stop regenerating soil in whatever way they are doing it, from cover cropping to (just short of) using synthetic chemical fertilizers, and the massive number of options in between. He is, however, suggesting that these are not adequate measures. They are driven by science, which is not enough.

The biodynamic method is driven by observation, experience, and a belief in the existence of forces that cannot be immediately seen or measured, but whose presence is proven in the resulting product. It is these cosmic influences, collected in the soil and taken up into the plant, that are removed along with the crop and therefore must be replaced. He is not denying the efficacies and even necessities of science in agriculture but rather saying that it stops short of completing the regeneration necessary to maintain the production of healthy, tasty food.

Steiner’s Lecture 5 describes the Biodynamic Compost Preparations, which when applied in very small doses, enliven and provide stimulus for the soil to again be able to collect the streams of cosmic force. They consist of common and recognizable plants variously treated and applied to compost heaps, the soil of which is then applied to the field or garden. There was no scientific underpinning then, or even now; he expected that the science would catch up eventually.

Look, it is a scientific fact that the moon causes the tides of the ocean and that the sun warms our atmosphere. These influences are easily perceived of course, and science is there to confirm the obvious and fill in the details. Can we propose that other planets and cosmic bodies take effect on earth too, although not in a way we can easily see, feel, touch, or smell? Can we do this ahead of science telling us it is so?

Heavens above, it has taken me a long time to write this article. I had to go back into the lectures quite a bit to see if I was on the right track. I even read a bit of Steiner poetry. I wrote long, meandering paragraphs about the contrasting yet inseparable dualities of matter and spirit, of science and spirituality. I did a lot of deleting.

I’ll have to leave it here. I must go outside and get giddy over spring.

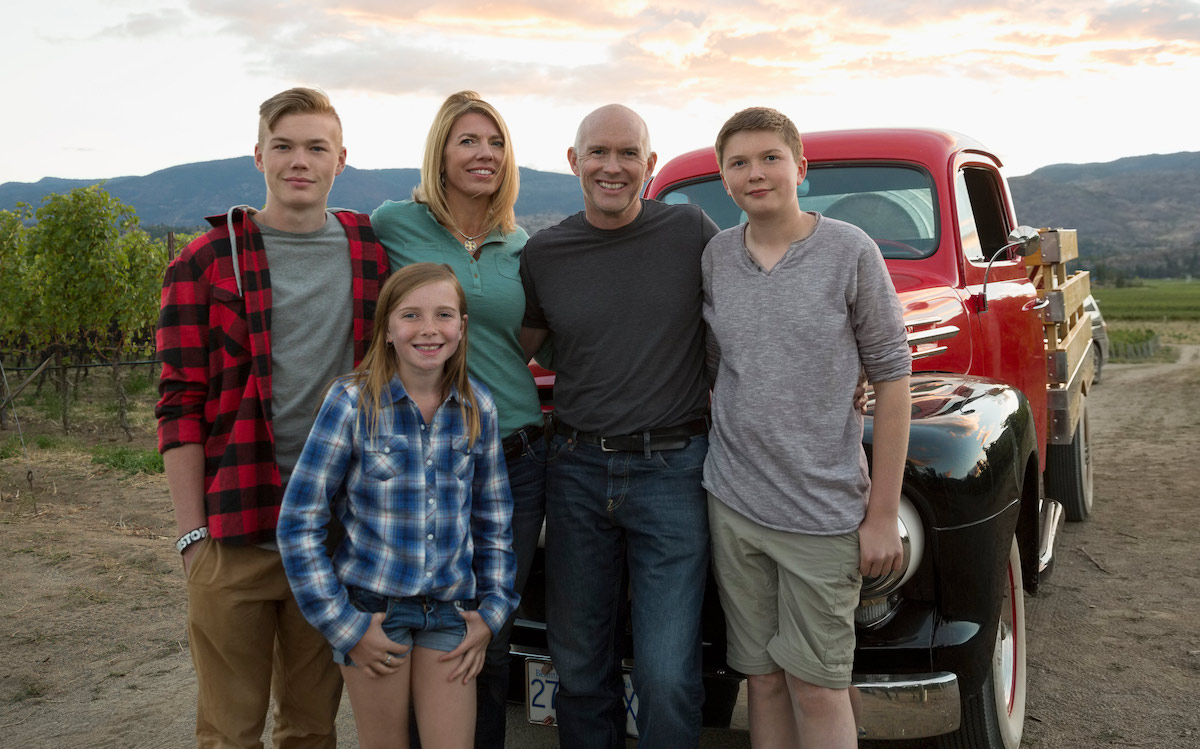

Anna Helmer farms with her family in Pemberton and would like to scientifically prove that the hundred-pound sacks of seed potatoes are getting heavier all the time. helmersorganic.com

Feature image credit: Helmers Organic Farm