Linerboard: A Love Hate Story

Randy Hooper

As one of the original conspirators of mulching with kraft linerboard ‘paper’ back 20 years ago, and a continuing fan, I would just like to say that if you listen to my words of wisdom and take this path, you may be really, really happy. Or maybe not. But here’s the deal:

25 years ago I worked with the late Eva Temmel, a self- taught intuitive permaculturalist. She taught me a thing or two, or 80. Eva wasn’t into mulch but the neat thing was that she somehow stumbled across dozens and dozens of used hospital sheets from Lady Minto Hospital and transplanted brassicas and lettuce under colourful rows of blue, green and yellow for weeks with no damage from rain or sunburn. Eva taught me to be unorthodox when it came to farming.

The concept of using paper as a mulch is not new—backyard and market gardeners have been using attened cardboard boxes in the aisles to keep weeds down for decades. The practice of using straw and hay mulch for weed control and water retention goes back millennia. Growing vegetables through paper mulch, on the other hand, doesn’t have much history. Like all mulches, the benefits are many: much less weeding, less soil compaction, and wetter and warmer soil. But for some of us, there is absolutely no joy in rolling up thousands of feet of plastic row cover and trundling it off to landfill. For some purists, it may seem antithetical to marry organic production methods and single use plastics.

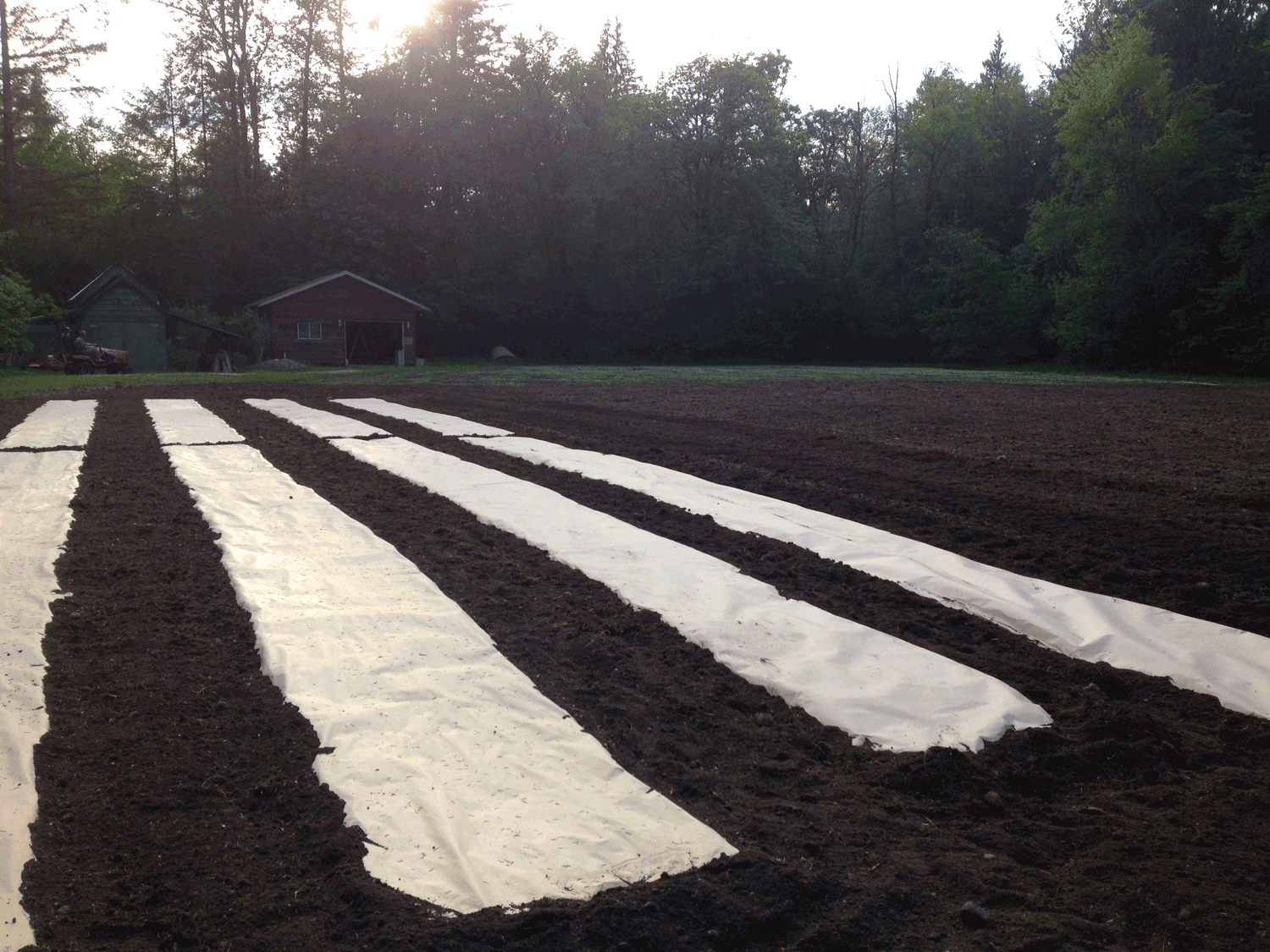

When I was back in the dirt again 15 years ago I took on a task far too hard—to convert about 20 acres of pasture back into vegetable production, with high weed pressure and nowhere near enough water. Mulching was the answer, and I chose paper. Most of the paper that was available in industrial sizes was too flimsy – the kind you use to mail a parcel. The Yellow Pages (remember those?) led me to Novapak in Richmond, a converter manufacturing all sorts of products from rolls of raw pulp fibre. The product I chose from them, and continue to recommend, is 40# linerboard, the same weight of bre used to manufacture laminated cardboard boxes. (40# means it weighs 40# per thousand square feet. A standard length we use is 5’ X 400 feet, 2000 sq. feet, so about 80# a roll.)

Bearing in mind that a few inches on each side are getting buried as you lay it, labouriously by hand, or with ease with a mulch layer, a 5’ wide sheet gives you a bit more than 4’ of row. Paper is much more expensive than plastic, but if you do the math, at a cost of, say, $.04 a square foot, vs. the cost of substantially more weeding and watering, the economic benefit is huge.

After an initial year of tests on a wide variety of crops, I decided that the only way to take on the other 14 acres was to go big or go home. I found a great mulch layer that worked perfectly for paper. It took just a few days to lay paper on our whole main field—17 acres.

In retrospect there was some major heartache, and for anyone who wants to have fun with paper, heed my wisdom. First, don’t look back. You know what I mean—it is nearly impossible to steer perfectly straight if you look behind you, and when you are laying paper, every time you look back you will steer a little crooked and end up with a big wrinkle or rip. Plastic stretches. Paper doesn’t. No field is perfectly flat, and lumps and bumps in the bed will also wrinkle the paper. However, paper does shrink, and after a few days of wet / dry cycles (dew and sun) many of those wrinkles will go away. What we did find that really helps is to have someone ride shotgun on the mulch layer itself, not just to shift balance, but to yell up to the operator to stop, or steer a tad left or right.

Paper shrinks—a lot. It’s quite amazing that a sheet of paper 400’ long will shrink up to a foot in length in just a few days. But it will literally rip apart if you don’t ease the pressure. An easy fix is slicing the paper every 80’ or so, right across the bed, covering the cut with a bit of dirt. These shorter lengths will shrink just a few inches and not rip. Do not cut holes for a few days, or start to transplant or direct seed before that paper has shrunk to its nal dimension. If you do seed right away through a hole you’ve engineered with a box cutter, and the paper literally shifts a few inches as it shrinks, the seed is now germinating in the dark, because the hole above it moved. Trust me—I learned the hard way.

Once the paper is down, walk the bed, making sure that all the edges and ends are buried. Wind is your enemy, and an exposed edge can let wind get underneath and create havoc. You cannot lay mulch paper in the wind. It is even harder to re-do it after the paper has blown all over the field. Been there.

The edges of the paper that are buried in dirt will start to break down within a few weeks. After that, you are once again left with a wind issue, because once the buried portion has rotted away, you now have a flat piece of paper lying on the beds that can be vulnerable if you’re direct seeding because there’s nothing to hold it down besides gravity. There is less of a risk if you have transplanted through it.

The only way I know to protect the integrity of the paper is to immediately, literally on the same day, sow buckwheat heavily in the aisles. Why buckwheat you ask? You can walk, kneel or drive on buckwheat and it bounces right back within a day, but the most important factor is that it germinates and sprouts in a few days, and by the time the sides of the payer have rotted out, the buckwheat is a couple of inches high. The wind blowing across your field is now riding across the top of the buckwheat, protecting the now exposed edges of the paper from going airborne.

What can you grow? Well, any plant that likes cold feet will do well, because the paper keeps the soil a few de- grees cooler—so kale, chard, collards, cabbage, Napa, Brussels and bok choi were a few very successful ones. Obviously there is a long list of what won’t work with paper—row crop like carrots, parsnips, beets, cilantro, radishes to name many. And there’s another list of varieties that just don’t make sense economically, an example being broccoli. Other crops that don’t grow well through paper are basil, tomatoes, eggplant and cucumbers. The soil temperatures just aren’t warm enough.

Because water was a big issue for me, paper was a saving grace. Whether in plastic or paper, if a chard plant is taking up a square foot, then all the rain that hits that square foot is going to go into the hole—a 10:1 water capture advantage over bare soil, and much slower evaporation. Unless your beds are dead flat and dead level you will have quite a few little lakes and ponds on the paper surface. I jab a hole in the paper at the lowest point of the puddles and let the water drain through. When planting out hard squash or zucchini, set transplants where you have poked holes, knowing that every bit of rain falling near those plants is going to drain right through those same holes—and for zucchini, you could be directing all the rain that falls over up to 10 square feet right to its roots.

Our two most outstanding successes were leeks and beans. Wait until the paper is wet and then punch holes through it with a ski pole (without basket). If you try that when the paper is dry it will rip. Drop leek transplant into hole. Water in transplants or wait for rain to set them in. Do not weed. Do not water. Don’t think about them for months. Come back in the fall or next spring and harvest. Same deal with beans—they were the best! Stab hole in paper. Drop seed. No weeding, no watering, and the best part? Crows and ravens, as you know, apparently have photographic memories and will carefully glean bean seeds, even while you are watching. Even while you are sowing. Well what a piss-off for them because they can’t extract them through those little holes in the paper.

Let me know if you have any fun stories about paper. Like how you hate the sound of ea beetles bouncing off the drum tight paper on summer afternoons—or how you write your eld plans and production notes in felt pen right on the beds.

Randy Hooper is an off-and-on again organic farmer, more off than on, and with less and less acreage each time over 25 years, on Saltspring Island, in Abbotsford, in Mexico, and currently in Ruskin east of Maple Ridge. He and his wife Annie own and operate Discovery Organics in Vancouver. His email is discoveryorganics@gmail.com.

I decided to stick with the traditional horizontal design I was experienced with, and build a mill. I ordered a set of 12” granite stones from Meadows Mills, bought a motor, pulleys, bearings and had a shaft machined locally. I made a trade with a sawmilling neighbour for a pile of dried birch he had in his basement for a furniture project he hadn’t gotten to. For the mill design, the beauty is in the simplicity.

I decided to stick with the traditional horizontal design I was experienced with, and build a mill. I ordered a set of 12” granite stones from Meadows Mills, bought a motor, pulleys, bearings and had a shaft machined locally. I made a trade with a sawmilling neighbour for a pile of dried birch he had in his basement for a furniture project he hadn’t gotten to. For the mill design, the beauty is in the simplicity.