Ask an Expert: Organic Agriculture 3.0

History of the Debate About the Future of Agriculture

Thorsten Arnold

This article was first published by the Organic Council of Ontario on January 18, 2019, and is reprinted here with gratitude.

The organic farm and food industry is facing major challenges. IFOAM, the international federation of organic agriculture movements, is spearheading a debate on how the organic movement can tackle these in the future. This blog summarizes the history of this debate and some questions of interest for Canada.

In 2015, Europe’s major organic farmer associations identified major challenges, with ongoing relevance for the present. Most importantly, the growth in organic production has been slow and farm conversion to organic practices are stagnating. Even if the current growth of 5% per year is sustained until 2050, the organizations concluded that the impacts of organic agriculture would remain insignificant with respect to the movement’s goal of reducing the adverse impacts of agriculture on the planet’s ecosystem and resource base. The organizations also identified several structural barriers within and outside of the organic sector, and posed the question, what could the next development phase of organic agriculture, coined Organic 3.0, look like?

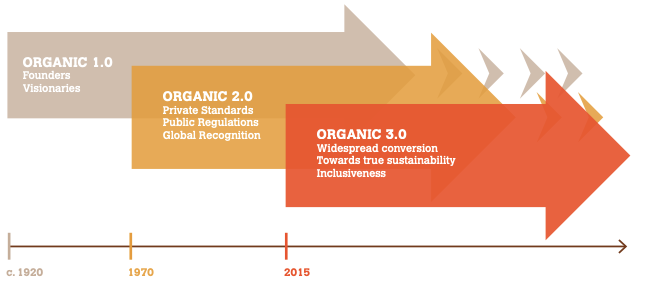

Organic agriculture is classified into three development stages. Organic 1.0 describes the early period, when farmers responded to the industrialization of farming with a call to respect natural cycles and soil health, and retain a lifestyle that is in tune with nature. This early phase was inspired by Rudolf Steiner’s agricultural courses but also with the warning about “Limits of Growth” by the Club of Rome. Organic 1.0 was characterized by a colorful and incoherent movement that was innovative but failed to link into the mainstream food system. Around 1970, a growing number of unsubstantiated organic/biological/ecological claims increasingly confused consumers and retail traders, highlighting the need for harmonizing the “organic trademark”. European farmer associations reacted by defining a number of guidelines and private organic standards (e.g. Demeter, Bioland, Naturland, BioSwiss, BioAustria), many of which are popular today. During the early 90s, governments throughout the world adopted national organic standards and equivalence agreements between these. This global harmonization enabled international trade in organic goods and also opened retailers to organic products. The successful shift from ideology to standard-driven production is subsumed as Organic 2.0. Today, private and national standards co-exist in many European countries, with private standards being widely recognized by consumers as more stringent and small-scale, whereas national standards cater to industrial organic production and processing.

IFOAM International did not favour a two-tier system, as many member countries do not share Europe’s history of successful private premium organic standards. In a follow-up paper (Nigli et al., 2015), the authors of Biofach 2015 re-formulate the five challenges of organic agriculture as (1) weak growth in agricultural production, (2) the potential of organic agriculture to provide food security, (3) competition from other sustainability initiatives including greenwashing, (4) transparency and safety in value chains, and (5) the need to improve consumer communication. While authors agree that a two-tier system is not necessary, they voice concern about the organic label losing its leadership claim amongst a multitude of emerging sustainability labels. Authors see the current stagnation of organic growth, and the slow speed of innovation in national standards, as a fundamental threat to the organic movement and its goals.

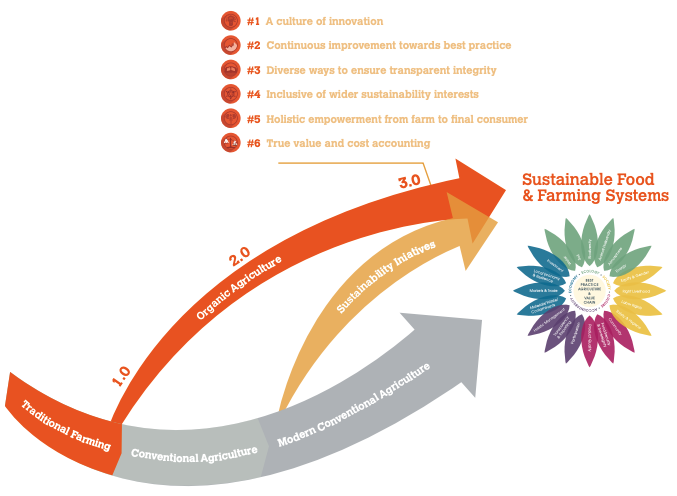

In 2016, IFOAM responded in a paper that gives direction to Organic 3.0. In recognition that “promoting diversity that lies at the heart of organic and recognizing there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach”, IFOAM identified six features that Organic 3.0 should address (IFOAM 2016, p3).

- Feature #1: A culture of innovation where traditional and new technologies are regularly re-assessed for their benefits and risk.

- Feature #2: Continuous improvement towards best practice, for operators along the whole value chain covering the broader dimensions of sustainability.

- Feature #3: Diverse ways to ensure transparency and integrity, to broaden the uptake of organic agriculture beyond third-party certification;

- Feature #4: Inclusiveness of wider sustainability interests through alliances with movements that truly aspire for sustainable food and farming while avoiding ‘greenwashing’;

- Feature #5: Empowerment from the farm to the final consumer, to recognize the interdependence along the value chain and also on a territorial basis; and

- Feature #6: True value and cost accounting, to internalize costs and benefits and encourage transparency for consumers and policy-makers.

With some further guidance to different players in the organic movement, IFOAM called upon national and regional associations to fill these features with meaning. Since then, organizations across the globe have engaged in a more focused discussion about the future of organic agriculture.

What Does the Future of Organic Look Like?

North America’s organic associations remain sceptical about a two-tier approach to the organic label. Still, farmers who strongly exceed the national standards feel insufficiently represented by the organic associations and unable to compete with some of the largest organic production corporations. Next to the Demeter biodynamic certification, there are at least two recent private initiatives that promote premium organic certification. Currently in its piloting phase, the Rodale Institute’s Regenerative Organic Certification (ROC) integrates animal welfare and labour fairness requirements and uses three tiers to reward leadership. Secondly, the Real Organic Project is an “add-on label to USDA certified organic to provide more transparency on these farming practices”. USDA organic certification is a prerequisite to participate in this add-on program. This family farmer-driven project embraces centuries-old organic farming practices along with new scientific knowledge of ecological farming.

In the face of these international developments, Ontario’s organic organizations must respond to the grassroots emergence of a de-facto two-tier system. This is not only driven by farmers who feel insufficiently represented by the “mainstream” national organic standards, but also by consumer understanding of the organic label. Organic-critical mainstream articles play a major role in consumer perception, such as a recent Toronto Star article “Milked”, which found less-than-expected differences between the milk from a large certified organic brand and conventional milk. Even though the article’s findings were based on misleading and unscientific grounds, it still points to a growing concern from consumers about the differences across the organic sector. How can consumers learn about these differences? And how do we, as part of Ontario’s organic movement, promote the national organic standard without abandoning those innovators that exceed the COS requirements, and strive for further recognition?

Organic 3.0 aspires to build leadership within the organic sector as well as bridges with mainstream agriculture. This means innovating beyond the COS requirements and sharing experiences with the entire agriculture sector. As Prof. Caradonna, U of Victoria, reports, many non-organic farmers are already taking up some of organic’s proven practices: cover cropping, reduced tillage, and smarter crop rotations. How can we strengthen this cross-over to maximize benefits for our shared planet? And, what can the organic sector learn from the innovative non-organic producers, e.g. for no-till field crops? How can the farming sector better generate, accumulate and pass on knowledge that is independent from input vendors, whose advice is biased by self-interest? How can farmers learn from each other to sustain farm profits, healthy people, and our beautiful planet?

Thorsten Arnold is a member of the Organic 3.0 Task Force of the Organic Value Chain Roundtable. Thorsten also serves on the board of the Organic Council of Ontario and currently works with EFAO as strategic initiatives & fundraising coordinator. Together with his wife Kristine, Thorsten owns Persephone Market Garden.

Feature image: Fig.1 Evolution of the organic movement (Source Arbenz et al., 2016)

Further reading:

OCO’S response to Toronto Star’s article Milked.

Organic agriculture is going mainstream, but not the way you think it is.

References

1. Niggli, U., et al. (2015). Towards modern sustainable agriculture with organic farming as the leading model. A discussion document on Organic: 3. Jg., S. 36.

2. Arbenz, M., Gould, D., & Stopes, C. (2016). Organic 3.0 for truly sustainable farming & consumption. 2ndupdated edition: IFOAM Organics International: ifoam.bio/sites/default/files/organic3.0_v.2_web_0.pdf.