Organic Stories: Covert Farms, Oliver, BC

Fighting Drought through Complex Ecosystems

By Emma Holmes

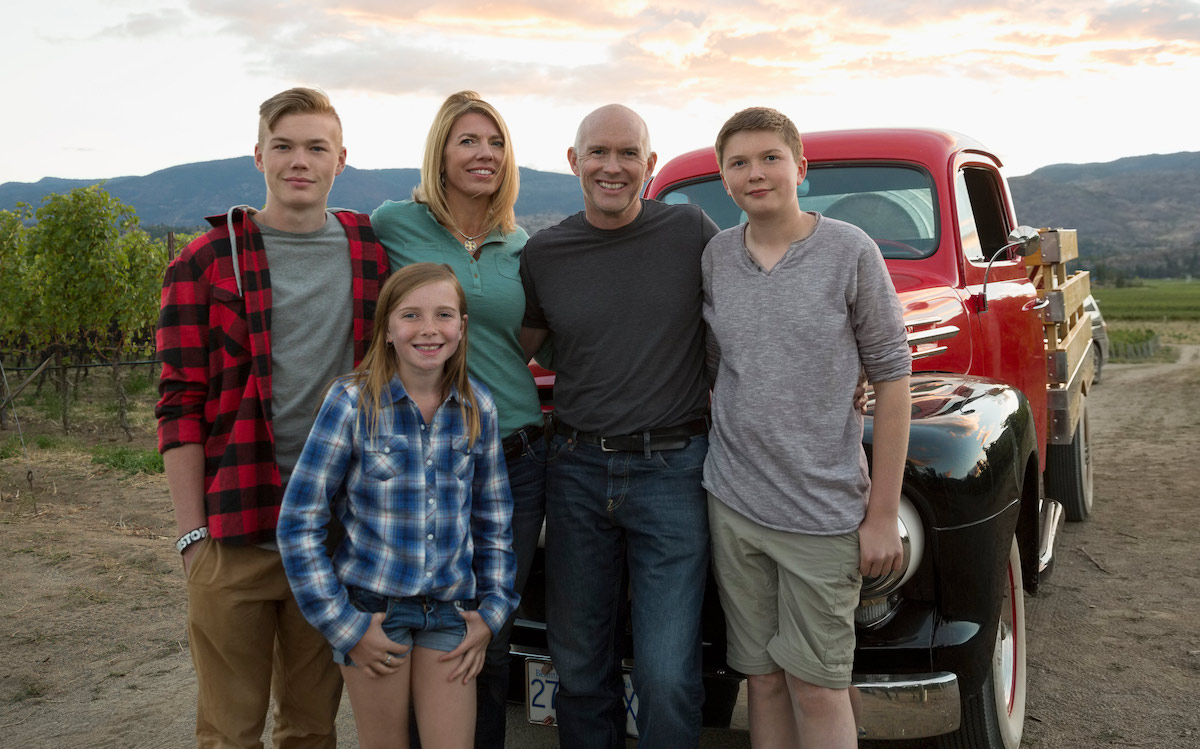

Irecently had the pleasure of visiting Covert Farms Family Estate in Oliver, where Gene Covert, a third-generation farmer, gave me a tour of his family’s 650 acre organic farm, vineyard, and winery. Gene’s grandpa George Covert bought the desert-like piece of land back in 1959, and although some laughed, thinking the land would not be suitable for agriculture, he, his son, and eventually grandson, Gene, have built the farm into a robust, flourishing, certified organic farm that embraces biodynamic, permaculture, and regenerative farming methods.

Gene studied ecosystem complexity as a Physical Geography student at UBC and has carried this learning through to his farming career, approaching it with a high level of curiosity for the natural world and experimentation. His wife, Shelly Covert, a holistic nutritionist, has been co-managing the family farm and in 2010 they were awarded the Outsanding Young Farmer Award BC/Yukon. Gene and Shelley are deeply connected to their land: “The relationships of our land are complex and most have yet to be discovered. As we learn more we find interest, intrigue, and humility.”

Like many places in BC, Oliver is expected to face increasing warmer and drier conditions. Already a drought prone desert, it is more important than ever to find ways to slow the water down, trap it at the surface, give it time to infiltrate, and store it in the soil.

The secret to storing more water lies in soil organic matter. Soil organic matter holds, on average, 10 times more water than its weight. A 1 percent increase in soil organic matter helps soil hold approximately 20,000 gallons more water per acre.1

The Covert’s guiding philosophy is that “only by creating and fostering complexity can we hope to grow food with complex and persistent flavours. Flavours are the ultimate expression of the mineralization brought about by healthy soil microbial ecosystems.” To increase the organic matter content of his sandy soil, Gene took inspiration from organic and regenerative farmers in other agricultural sectors and began experimenting with cover crop cocktails, reduced tillage, and integrating livestock into his system.

Cover Crop Cocktails

Cover crop cocktails are mixtures of three or more cover crop species that allow producers to diversify the number of benefits and management goals they can meet using cover crops. Farmers like Gabe Brown are leading the way and driving the excitement around cover crop cocktails, and research is following suit, with universities starting research programs such as Penn’s State Cover Crop Cocktail for Organic Systems lab.2

To help him in meeting the right mix for his system, Gene uses the Smartmix calculator, made by farmers for farmers3. He has found that seven or more species affords the most drought tolerance. He uses a combination of warm and cool season grasses, lentils, and brassicas. Some of the species in his blend include guargum, a drought tolerant N-fixing bean, radish to break up soil at lower depths, and mustards as a cutworm control.

Gene plants Morton lentils right under the vine to fix N and suppress downy brome. This type of lentil was developed by Washington State University for fall planting in minimum tillage systems. Crop establishment is in the fall and early spring, which is when evapo-transpiration demand is minimal, thus improving water-use efficiency.

The diverse benefits of his cover crop include N fixation, increase in soil organic matter, weed control, pest control, and increased system resilience in a changing climate.

Low-Till

Frequent tillage can negatively impact soil organic matter levels and water-holding capacity. Regular tillage over a long-time period can have a severe negative impact on soil quality, structure, and biological health.

The challenge for organic systems is that tillage is often used for weed control, seedbed preparation, soil aeration, turning in cover crops, and incorporating soil amendment. Thus, new management strategies need to be adopted in place of tillage. Cover cropping, roller crimping, rotational grazing, mowing, mulching, steaming, flaming, and horticulture vinegars are cultural weed control practices that can be used in organic systems as an alternative to tillage. The most successful organic systems embrace and build on the complexity of their system, and utilize several solutions for best results.

Gene used to cultivate five to six times a year, mostly for weed control, but now cultivates just once a year to incorporate cover crop seeds under the vines. Instead of regular tilling to control weeds, he uses cover crops that will compete with weeds but that won’t devigorate the crop and that can be controlled through non-tillage management strategies like roller crimping and rotational grazing. For cover crop seeds between the rows, he uses a no-till seeder.

Intensive Rotational Grazing

Integrated grazing sheep or cattle in vineyards is not a new concept, but it became much less common since the rise in modern fertilizers. It has been increasingly gaining steam in recent years due to the myriad benefits it provides. The animals act as cover crop terminators, lawn mowers, and weed eaters while also improving the overall soil fertility and biological health4. The appropriate presence of animals increases soil organic matter, and some on-farm demonstration research out of Australia showed significant reductions in irrigation use, reduced reliance on machinery, fuels, and fertilizers, and increased soil organic matter.5

Incorporating livestock into a horticultural system adds a completely new management challenge and thus level of complexity. It comes with the risk of compaction and over grazing if not managed properly. The key is to move herds frequently, controlling their access to different sections and never letting them stay too long in one area. As well, the grazing window needs to be limited to after harvest and before bud-break to prevent damage to the cash crop

Increased Resiliency

Since experimenting with and adopting these management practices, Gene has found his cost of inputs has dropped and he has noticed a significant increase in soil organic matter and reduced irrigation requirements. Based on his success so far, he has a goal of eventually dryland farming. No small feat on a sandy, gravelly, glacio-fluvial soil in a desert climate facing increasing droughty conditions!

On-Farm Demonstration Research

A farmer’s experience and observations are critical in problem solving and the development of new management practices. Increasing farmer-led on-farm research is fundamental to improving the resiliency of producers in the face of ongoing climate change impacts, such as drought and unpredictable precipitation.

Farmer-led on-farm research compliments and builds experience by allowing a farmer to use a small portion of their land to test and identify ways to better manage their resources in order to achieve any farming goal they have, including climate adaptation strategies such as increasing soil organic matter to reduce irrigation requirements. The beauty of on-farm demonstration research is that it is farmer directed, it can be carried out independently, and it uses the resources a typical farmer would have on hand.

If you’re inspired by an idea, or a practice you have seen used in another agricultural system and are interested in conducting your own field trials, I highly recommend the BC Forage Council Guide to On-Farm Demonstration Research: How to Plan, Prepare, and Conduct Your Own On-Farm Trials.6 It is an accessible guide that covers the foundations of planning and conducting research, allowing you to achieve the best results. While it was created for the forage industry, the guide covers the basics of research and is applicable to farmers in any sector.

My highest gratitude and praise for the farmers who are finding the overlaps at the edges of agricultural models, where one becomes another—and leading the way into the new fertile and diverse opportunities for sustainable food production in a changing climate.

Thank you to Gene Covert and Lisa Wambold for their knowledge, passion, and insights.

Emma Holmes has a BSc in Sustainable Agriculture and an MSc in Soil Science, both from UBC. She farmed on Orcas Island and Salt Spring Island and is now the Organics Industry Specialist at the BC Ministry of Agriculture. She can be reached at: Emma.Holmes@gov.bc.ca

References and Resources:

1. Bryant, Lara. Organic Matter Can Improve Your Soil’s Water Holding Capacity. nrdc.org/experts/lara-bryant/organic-matter-can-improve-your-soils-water-holding-capacity

2. agsci.psu.edu/organic/research-and-extension/cover-crop-cocktails/project-summary

3. greencoverseed.com

4. Niles, M.T., Garrett, R., and Walsh, D. (2018). Ecological and economic benefits of integrating sheep into viticulture production. Agronomy and Sustainable Development. 38(1). link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs13593-017-0478-y

5. Mulville, Kelly. Holistic Approach to Vineyard Grazing. grazingvineyards.blogspot.com

6. BC Forage Council. (2017). A Guide to On-Farm Demonstration Research. Farmwest.com. farmwest.com/node/1623