Footnotes from the Field: Fall 2019

Water, Water, Everywhere… and Not a Drop to Drink!

Marjorie Harris

Special thanks to Tim Rundle of Creative Salmon for helping pull this synopsis on Aquaculture together!

The Canadian Aquaculture Standard CAN/CGSB-32.312 was published in 2012, with the new revision released in February 2018. The Aquaculture Standard stipulates the following:

Section 1.3: In the event of any conflict or inconsistency between this standard and CAN/CGSB-32.310 /311, this standard will take precedence.

Section 1.4: Prohibited substances list is identical to organic agriculture except that the soil amendments clause is expanded for aquaculture – Soil, sediment, benthic, and water amendments that contain a substance not listed in clause 11.

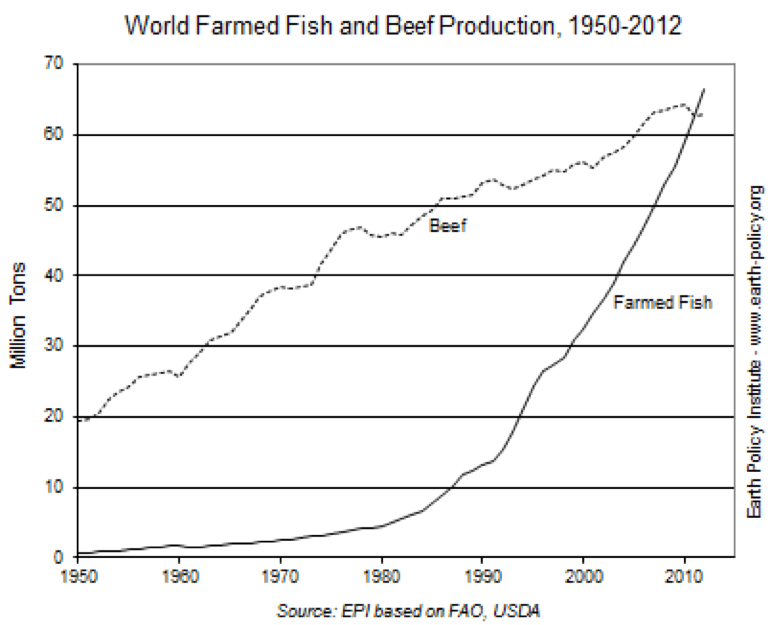

Seventy percent of our blue planet’s surface is covered by the oceanic ecosystem. Short of desalination, that water isn’t available for drinking, and yet the oceans’ salt water has all of the micronutrients required for human health. As of 2012, farmed fish production throughout the world outpaced beef production.1 Surprisingly, 60% of British Columbia’s exported agricultural products come from aquaculture operations. In 2017, Canada’s wild fish catch harvest was 851,510 million tonnes, and the aquaculture harvest was 191,416 million tonnes.2

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) tracks 179 wild fish stocks worldwide, and states that “fishing is a global industry, and of key importance to Canada. Sadly, overfishing, illegal fishing activities, and the destruction of ocean ecosystems are serious global issues that require immediate and continuing attention. Canada is committed to combating these problems.”3

According to the Earth Policy Institute, these trends illustrate the latest stage in a historic shift in food production—a shift that at its core is a story of natural limits: “The bottom line is that getting much more food from natural systems may not be possible.” In terms of resources required for livestock production, “Cattle consume seven pounds of grain or more to produce an additional pound of beef. This is twice as high as the grain rations for pigs, and over three times those of poultry.” In contrast, states the Earth Policy Institute, “Fish are far more efficient, typically taking less than two pounds of feed to add another pound of weight. Pork and poultry are the most widely eaten forms of animal protein worldwide, but farmed fish output is increasing the fastest.”1

Clearly, it looks like aquaculture is here to stay as a form of high quality, lower input, method of protein production, but is it the answer? Conventional aquaculture systems have left a legacy of controversy and environmental issues when operated in natural ecosystems.

Can organic aquaculture meet the needs for human food production and be environmentally friendly?

On January 25th, 2019, I attended an organic aquaculture training given by Tim Rundle, General Manager of Creative Salmon, North America’s only major producer of indigenous Pacific Chinook (King) salmon and Canada’s first producer of certified organic farm-raised salmon.

The biggest take away for me was that I was impressed with the standard’s requirements for the farmed species to be indigenous or adapted to the region. This requirement is a huge improvement over conventional systems. For example, Atlantic salmon being raised in conventional farmed systems in BC coastal waters are plagued by sea lice, while Creative Salmon’s Chinook salmon have a natural resistance to sea lice and no parasite treatments have been required—the species is indigenous or adapted to living where it is being raised with respect to its natural requirements.4

In an article featured on Aquaculture North America, Liza Mayer writes, “Rundle is first to admit that organic farming is not easy. Compared to conventional farming, fish raised under organic standards are provided added space in the pen enclosures,” in a parallel to the stocking requirements for land-based livestock in the organic standards. Moyer goes on to explain that “Chinooks, known to be more aggressive than their Atlantic cousins, swim freely because there are fewer of them in the pen, but it also means lower harvest volume. For Creative Salmon, that is 8 kilograms of fish per cubic meter maximum, although organic standards allow up to 10 kilograms of fish per cubic meter. Density in conventional farming could be from 20 to 25 kilograms per cubic metre.”5

What does the Aquaculture Standard cover?

Aquaculture is defined as the cultivation of crops or livestock in a controlled or managed aquatic environment (marine and land based freshwater and salt water operations). Aquaculture products are crops and livestock, or a product wholly or partly derived therefrom, cultivated in a controlled or managed aquatic environment. Aquaponics is also covered by the new Aquaculture Standard and is defined as a production system that combines the cultivation of crops and livestock in a symbiotic relationship. The products of fishing and wild animals are not considered part of this definition.

Recently, conventional aquaponics received some negative press due to the announcement that CanadaGap would be withdrawing aquaculture from its FoodSafe certification programs due to the use of antibiotics, which end up being incorporated into the plant and livestock products. Organic aquaculture does not allow for the use of antibiotics, and so the discussions around aquaponics need clarity to highlight the differences between conventional and organic productions systems. As aquaponics entrepreneur Gabe Cipes explains, “We have two conventional agricultural systems, aquaculture and hydroponics, that are dependent on chemical inputs and are decidedly bad for human health and the health of the environment.”

Cipes, who has extensive experience in organic and biodynamic farming, says that “If those two conventional systems are combined [into aquaponics] and managed according to the organic Aquaculture Standards, then the fish take care of the plants and the plants take care of the fish and there is no need for chemical or conventional inputs.” The benefit of aquaponics, according to Cipes, is the ability to “create a closed loop ecology that is beneficial for humans and our ecology. It is a high density, low foot print method of food production that could be an integral and biologically secure part of the future of food security and sovereignty if given the opportunity.”

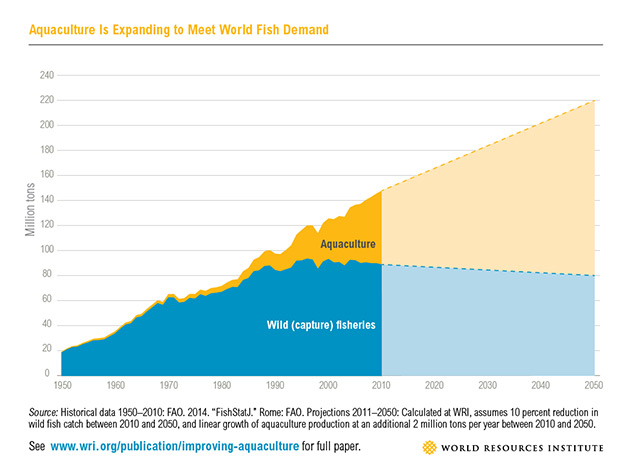

Aquaculture is already producing more fish than wild catches and the predictions are that aquaculture will keep growing at a steady rate. British Columbia is a leading salmon producer in the world and is Canada’s leader in aquaculture production. There is tremendous opportunity to expand organic aquaculture production in BC!

Hungry for More Aquaculture Info?

World Resources Institute projects that aquaculture production will need to more than double by 2050. But how to get there sustainably? Check out their findings, along with the recommendations they’re making to transform the aquaculture industry: wri.org/publication/improving-aquaculture

Marjorie Harris, BSc, IOIA VO and Organophyte.

Feature image: Wapta Falls, Yoho Park, BC. Credit: Keith Young (CC)

References

1. Earth Policy Institute: earth-policy.org/plan_b_updates/2013/ update114

2. Fisheries and Oceans, Fast Facts:

waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/Library/40782281.pdf

3. Fisheries and Oceans Canada:

dfo-mpo.gc.ca/international/index-eng.htm

4. Rundle, Tim. (2019, January), Creative Salmon. Presented at the Organic Aquaculture Training of the International Organic Inspectors Association.

5. Mayer, Liza. (2018, February). Creative Salmon: In a class of its own. Aquaculture North America: aquaculturenorthamerica.com/creative-salmon-in-a-class-of-its-own-1872