Footnotes from the Field: Mother Earth is Heating Up

BC Crop Adaptation & Diversification in Climate Change

Marjorie Harris BSc, IOIA V.O. P.Ag

I have stood on my back porch trying to imagine what a three kilometer high Cordilleran Ice sheet would have looked like here 12,000 years before the last big melt. It is estimated that people arrived in BC’s virgin landscape only 9,000 years ago.

Climate change on a geological time scale is undeniable. Long term climate change trends are difficult to observe from year to year and climate change over a lifetime may be imperceptible especially with a variety of shorter and longer climate cycles that can bring on their own periodic dramatic weather events.

Here in BC our usual climate patterns are regularly perturbed by El Nino, La Nina, and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. The El Nino cycle fluctuates over three to seven years. During El Nino years inland temperatures tend to be warmer and drier with warmer coastal waters that push salmon stocks further north to colder water. La Nina years are characterized with colder inland temperatures with heavier winter snow packs and colder coastal waters. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation pattern shifts temperatures and precipitation over 20 to 30 year periods that correspond with dramatic shifts in salmon production.

We have now entered a new epoch of human induced climate change. Analysis of global climate data provides unequivocal evidence that worldwide average temperatures have risen significantly and at a more rapid pace then usually observed in geologic time frames. The effects of climate change are region specific and variable across the world. The effects are most pronounced in high latitude and high-altitude areas.

What are the predicted impacts of climate change on BC crop production, pest and disease burden, weed control, and water resources?

There has already been a measurable shift to warmer average temperatures year round throughout the province generally speaking. However, climate change impacts vary region to region. Warmer winter temperatures have been more pronounced in the far north. In the southern part of the province the growing season has lengthened. There will be more very hot days in summer and extended droughts with higher risks of fire with drier conditions.

Crop production: Key cash crops will lose viability to grow under new climate conditions. Growers will need to diversify in crop production to meet the new growing conditions. In the Okanagan region, longer warmer growing seasons favor red wine grape varieties over cooler temperature white and ice wine grape varieties. In the Okanagan wine producers are replacing grapevines for varietals that prefer more warmth.

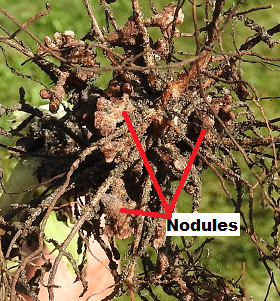

Pest and disease burden: Milder winter temperatures allow a greater number of pests to survive overwintering, increasing the pest burden for the following season. Timing of pest control will need to be adjusted as pest life cycles respond to temperature increases. For strategic pest management increased pest surveillance will be crucial to prevention and management.

Pests will extend range to higher altitudes with warming trends. One example is the spread of the mountain pine beetle from north to south across the province under the influence of milder winters. Many invasive insects and disease vectors such as mosquitoes, ticks, and rodents, will be able to extend their geographical ranges.

For BC, a rare anthrax outbreak occurred in Fort St. John in October 2018, killing 13 bison. Rainy weather and warmer soil temperatures allowed the bacteria deep underground to migrate to the soil surface and become an infective agent.

Weed Control: It is predicted that invasive plant and weed species will expand their ranges with climate change impacts. Weeds with efficient seed dispersal systems will invade faster than weeds that rely on vegetative dispersal. Higher carbon dioxide levels may cause some weeds to grow more vigorously. Disturbed habitats and fields after drought will be more easily colonized; therefore, cover cropping will become more imperative.

Water management: Climate change is predicted to bring substantial changes to water resources. The type of precipitation is already observably shifting to more rain, intense rain events, and less winter snowpacks. Persistent droughts are becoming more common during the summer months.

Most of BC’s alpine glaciers are predicted to continue to retreat and disappear within the next 100 years. Warming spring temperatures coupled with reduced snowpacks will result in earlier springs freshets, reduced summer flows, and increased peak flows for many of BC’s watersheds.

What can we learn from the past: BC’s prehistoric climate records demonstrate that in previous centuries the province has experience more frequent severe droughts than have occurred in the past few decades, irrespective of climate change.

For the last 4,000 years the planet has actually been in a long cooling period. When key crops failed repeatedly, causing food shortages, people migrated to new locations and diversified crop production. Moving away to new lands is not a current option on our fully explored planet.

Anthropological Archaeologist Dr. Jade d’Alpoim Guedes conducted research into the rapid cooling periods of the last 5000 years and made some correlations to climate warming:

“The impacts of warming going forward are going to be quicker and greater, [than global cooling], and humanity has had 4,000 years to adjust to a cooler world,” d’Alpoim Guedes said. “With global warming these long-lasting patterns of adaptation will begin to change in ways that are unpredictable,” she said. “And there might not be the behavioral flexibility for this, given current politics around the world.”

Also mechanized, industrialized agriculture and global agricultural policy are pushing us toward mono-culture of crops, said d’Alpoim Guedes. “We need to move in the opposite direction instead. “Studies like ours show that bet-hedging and investing in diversity have been our best bets for adapting to climate change,” she said. “That is what allowed us to adapt in past, and we need to be mindful of that for our future, too.”

So, the question of the 11th hour is, can we as human beings cooperate together to manage ecosystems and agricultural food systems to adapt and diversify quickly enough to prevent ecosystem collapses and famines?

Marjorie Harris is an organophyte, agrologist, consultant, and verification officer in BC. She offers organic nutrient consulting and verification services supporting natural systems.