Susanna Klassen

I have a confession: I live beside an amazing organic farm, and I buy imported organic vegetables. Not all the time! My partner and I are members of our neighbour’s Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program (it’s the best), we grow some vegetables on our own burgeoning little farm, and we go to the farmers’ market on many a weekend. But in the depths of winter when I am inspired by a specific recipe, I am grateful for the imported organic peppers from Mexico, or the cauliflower from California, and all the hands that brought it to our small coastal BC town.

Perhaps, like me, you have stood in the organic produce aisle and contemplated the similarities of its bounty to what you would get from your (or your neighbour’s) organic farm. Are these peppers grown with the same requirements? What were the impacts on surrounding plants, animals, and waterways? Were the workers treated differently from how they would be on an organic farm in Canada?

Or, perhaps also like me, you’ve wondered about who actually gets to make decisions about the direction of the organic sector in different countries. You may have heard people criticize the weakening of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) organic standards over time. Do these critiques also apply to Canadian standards? Where does Mexico fit in?

Canada, the US, and Mexico all have significant agri-food trade: all three countries are within each other’s top four export trade flows for agricultural products1. Many people living in Canada depend on this imported produce from Mexico and the US, especially in the winter months.

Globally, inter-governmental negotiations around organic trade have focused on bi-lateral “equivalency arrangements” (EAs). Where an EA is in place, national governments have agreed to consider organic products certified under the other country’s organic regime to be equivalent to their own based on a comparison of regulatory systems2. Canada has EAs in place with both the US and Mexico2. The US does not currently have an EA in place with Mexico, as Mexico does not recognize the USDA’s standards as equivalent3.

The EA between the US and Canada focuses on addressing a limited number of controversial production practices that differ between the two jurisdictions (e.g. antibiotic use and hydroponic production), with limited mention of other requirements in either country’s detailed organic management standards4. The Canada-Mexico EA excludes livestock products, where livestock products produced in Mexico must be certified to the Canadian organic standards by a Canada Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) accredited certification body. In other words, while the Canadian government has agreed to treat organic products from the US and Mexico as “equivalent,” it does not mean that the detailed organic standards requirements in each country are the same.

Now, back to the peppers from Mexico and the cauliflower from California. To better understand how organic requirements differ between these three countries with such tightly integrated food trade, I (along with colleagues from the University of British Columbia) did some research to look beyond what would be included in an EA. Specifically, I was interested in how the national organic standards in each of these countries—each with well-established organic sectors and regulatory regimes in place—required or promoted sustainability, including ecological and social dimensions.

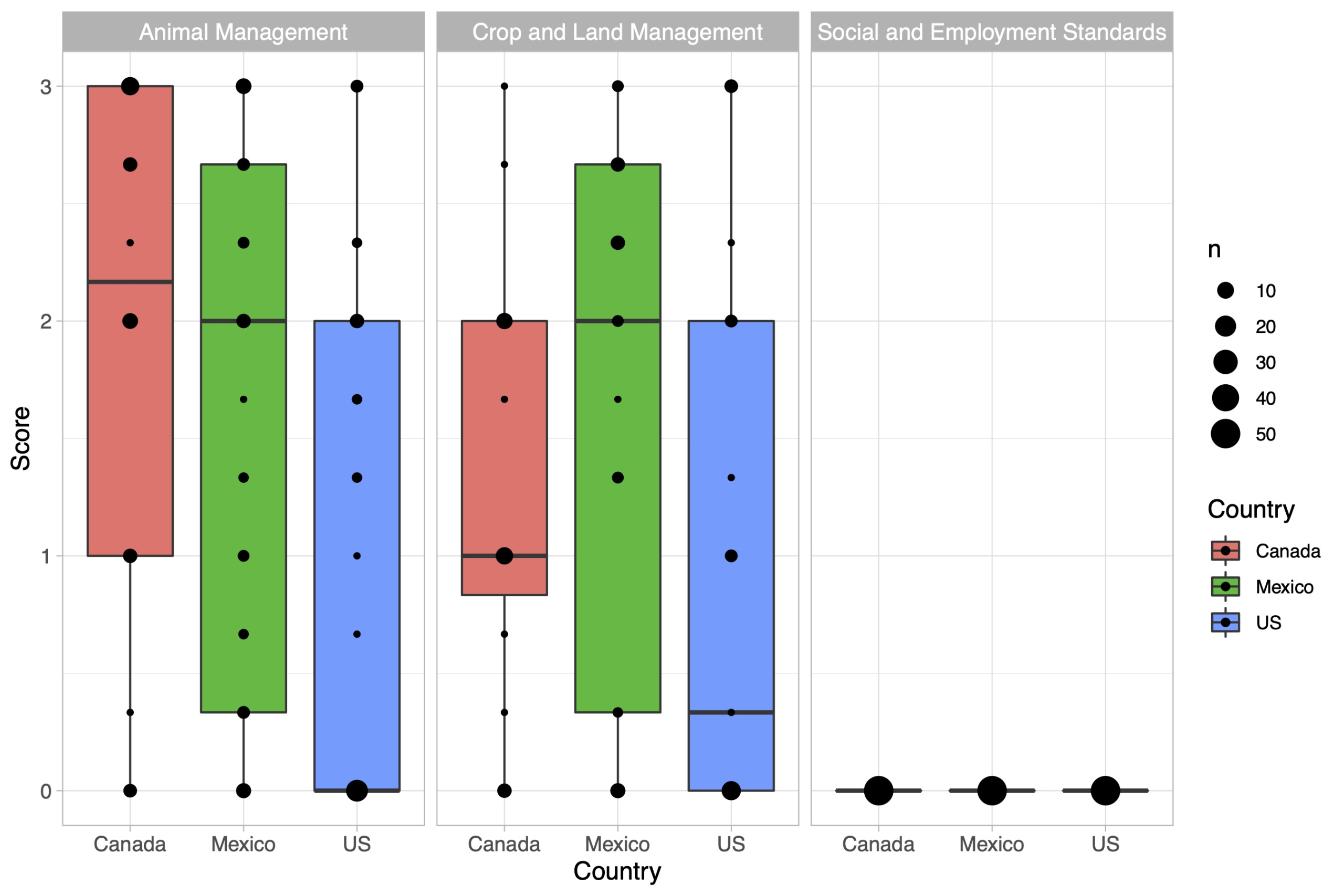

To answer this question, we built a framework of benchmark sustainability practices that we used to evaluate the requirements in the three national organic standards. This framework included practices (121 in total) related to crop and land management (e.g. soil health and fertility), animal management (e.g. outdoor access requirements), and social and employment standards (e.g. occupational health measures). We then scored each country’s organic standards based on the extent to which practices in each of these categories were required in the standards.

We found that the three countries’ organic standards were different from each other in several ways (Figure 1). For practices related to animal management, Canada consistently scored the highest. In particular, the Canadian standards contained clearer requirements for the general health and wellness of animals, transportation and handling of animals, and regulation of painful procedures and slaughter. Canada and Mexico scored similarly in most other categories. The US organic standards scored consistently lower across all sub-domains relating to animal management. Within the crop and land management domain, we found that Mexico had the highest scores for practices in most sub-domains except the presence of semi-natural habitat, where the Canadian standards were superior. The US also had the lowest score overall in this domain. We did find one commonality across the board: none of the countries’ standards contained any requirements related to social and employment standards.

Most readers are probably intimately familiar with the organic standards, so this likely isn’t new to you. But for me, the most important result of our research was not actually about the standards at all, but the formal processes for setting and maintaining the organic standards in each country—the standards governance. To compare these processes, we conducted interviews with 14 experts who have been engaged with development of the organic standards, international equivalency, or agricultural trade in one or more of the three countries.

This is where Canada really stood out. All three countries have a multi-stakeholder committee that serves as a standards governance body and contributes to the review of the national organic standards in some way. These committees are somewhat similar in their composition in that they include representation from producers, processors, and environmental or public interest groups. However, they differ in the level of control they have over decision-making, as well as the extent of government involvement. Only in Canada does this committee (the “Technical Committee”) have full control over decisions about the organic standards. Canada’s committee is convened by a government body (the Canadian General Standards Board or CGSB) that has no influence over the standards themselves, and is also distinct from the CFIA, which oversees the regulation and enforcement of the standards for organic agriculture.

In contrast, the equivalent committees in the US and Mexico—the National Organic Standards Board in the US, and the National Council for Organic Products in Mexico—do not have direct influence over the standards, but rather are consulted by the government body that ultimately makes decisions about the standards for organic agriculture in each country (the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service in the US, and the National Agro-Alimentary Health, Safety and Quality Service, or SENASICA, in Mexico). In other words, it is government officials—not the organic community or other relevant stakeholders—who have control over the standards in the US and Mexico.

This finding matters because it shows that Canada’s organic sector has processes in place to ensure that the organic standards are not shaped by a single interest, but that changes to the standards must be negotiated and informed by multiple relevant interests in the sector, not just those with the most power. While this might make it seem like changes happen slowly, this important work of the Technical Committee (and the Working Groups that support it) also ensures that changes that are made are debated, informed, and ultimately, supported by a broad base of actors.

If the organic standards are the backbone of the organic sector, the participatory standards governance processes are the beating heart. The process may not be perfect—there are still many important questions about who should pay for the standards review process, the amount of volunteer time that goes into it, and representation on the various groups and committees, but our research suggests that this model is worth participating in, building on, and protecting.

Like most good research, our project has left me with more questions than answers (How will future trade agreement negotiations influence the trade of organic products? How will the organic community support social justice outside of the organic standards?). I still think a lot about those peppers from Mexico, but at least I feel more confident that their organic standards have pretty strong requirements for ecological health of the landscapes they’re cultivated in. And, more than ever before, I am quick to correct anyone that equates organic certification in Canada with the USDA National Organic Program. Even if our governments view the organic products as equivalent, these two things are not the same.

This article is based on research published in the Journal of Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems. You can find the full article here.

Susanna lives in qathet where she and her partner are starting a small farm and raising their daughter as guests on the beautiful territory of the Tla’amin Nation. She did her PhD about organic agriculture in Canada and is now a postdoctoral researcher and instructor at the University of Victoria.

References

1 Chatham House. Resource Trade. 2021 [cited 2022 Feb 7]. resourcetrade.earth. Available from: resourcetrade.earth

2 Canadian Food Inspection Agency. Organic equivalency arrangements with other countries [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 15]. Available from:

inspection.canada.ca/en/food-labels/organic-products/equivalence-arrangements

3 USDA Agricultural Marketing Service. International Trade with Mexico [Internet]. [cited 2022 Aug 26]. Available from: ams.usda.gov/services/organic-certification/internation-al-trade-mexico?utm_source=pocket_mylist

4 Government of Canada. Canadian Food Inspection Agency. 2020 [cited 2021 Aug 3]. United States-Canada Organic Equiv-alence Arrangement (USCOEA) – Overview. Available from: bit.ly/3U14Izv

Featured image: Alliums going to seed at UBC Farm. Credit: Susanna Klassen.