By Ron Berezan

This article was first published by The Canadian Organic Grower magazine in Summer 2011, and is reprinted here with gratitude.

“When the well is dry, we know the worth of water.” – Benjamin Franklin, 1746

Turn on the tap and there it is; that shimmering, miraculous substance that flows through our rivers and lakes, our soils and plants—the rain that falls and the air we breathe, and indeed through the very eyes that read this text and the hands that hold this page. While millions of people around the world spend hours every day in the search for safe and drinkable water, we who live in relative water luxury, turning on the tap at will to meet our needs, are slower to recognize that water is a limited and very precious resource, without which there can be no life. For most of us, the well has never been dry.

Canadians are among the highest water consumers in the world, using an astonishing 600–700 litres of potable water per person per day in cities across this country.1 Yet if we consider the water used to grow the food we eat, agriculture being the most water- intensive human activity on the planet, not to mention other industrial water uses, our true rate of consumption is much higher. The good news is that through simple conservation measures, both in household and agricultural activities in Canada, our per capita water use has been decreasing in recent years. Given the marked decline of river levels on the prairies of the past few decades, along with other predicted changes in the hydrological cycle associated with climate change,2 there is little doubt that the years ahead will challenge us to draw much deeper from the well of wise water use.

One of the least explored and under-utilized options for water conservation in Canada is household grey water recycling. While other more arid regions of the world have been using grey water extensively for decades (some southwestern American states are now mandating grey water use in new residential developments), most Canadians are still unfamiliar with the very term. Household “grey water” by definition is any water that has been used for cooking, washing dishes, bathing or doing laundry. Grey water is to be distinguished from “black water” which is water that contains human waste, i.e. toilet water. Some water experts also include harvested rainwater from rooftops in the category of grey water, although there are notable differences between the two.

Apart from the obvious reduced water consumption associated with grey water use, there are two other compelling arguments in its favour. Firstly, whenever we use tap water, we are using energy—energy that has gone into the purification process as well as the pumping process to pressurize the lines that deliver water to our homes. Reducing water use also reduces energy use.

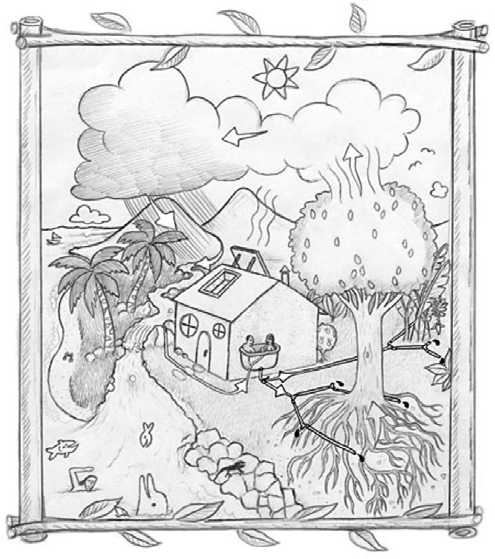

Secondly, grey water, when used in the landscape, comes with an added bonus: nutrients! All of the residual food waste left in our kitchen sink after washing dishes, and the soap itself (providing it is fully biodegradable) can become fertilizer for our gardens. As a common permaculture adage suggests, “pollution is an unused resource.” Indeed, when we consider natural systems, all waste from one organism or one process becomes food for another. Careful, appropriate grey water use in the landscape can connect our home ecology more firmly to the ecology of the place that we inhabit.

Before rowing our boat any further down the grey water stream, however, we should pause to consider the boulder lurking just below the surface—the question of regulation. Provincial plumbing codes and municipal bylaws vary throughout the country and many do not address the option of using grey water in the landscape at all. (They usually address using grey water inside the home for toilet flushing.) Suffice to say when I contacted municipal and provincial authorities in Alberta and asked, “Is it acceptable for me to bucket out my bathtub and use the water for my trees?” I was given a resounding “Yes!” in response.

When I further asked whether I could develop a more efficient way of moving the water from the tub to the trees, the response was more tentative and uncertain. It seems that outdoor grey water use is a ‘grey area’ in most jurisdictions in Canada. The bottom line is that you need to establish what is permitted where you live before you develop a grey water system.

Grey water advocate extraordinaire Art Ludwig, author of the highly useful Create an Oasis with Greywater,3 observes that the biggest mistake people make when using household grey water is that they contain the water in cisterns or buckets. The result is anaerobic decomposition of the nutrients and the inevitable unpleasant smells that come with it. Grey water should be confined no longer than 24 hours and ideally should be moved immediately from the source to the destination. Furthermore, any plumbing lines installed for grey water must be completely separate from water supply lines to ensure that no cross-contamination of potable (drinking) water can occur. While the health risks associated with grey water use are relatively very small, most grey water system designers recommend that there be minimal opportunity for contact between grey water and people, and that it be used to water perennial gardens, trees, and shrubs rather than annual vegetables.

Ludwig recommends keeping grey water systems as simple as possible by avoiding pumps, filters and other mechanisms that can easily clog up with particulate matter. Indeed, placing a basin in the dish sink or bucketing out the bathtub, though minimalist, can be a very effective option, particularly for occasional use.

For those who desire a slightly more automated system, Ludwig’s top recommendation is what he refers to as a “branched drain to mulched basin” design. Simply described, this system involves cutting into the existing drain pipe below a sink or bathtub and installing a ‘gate valve’ that allows you to direct the water outside through 1½-inch flexible PVC pipe and a series of ‘double ells’ that split the water into a few different directions.

Once outdoors, the flexible PVC is just below ground surface or beneath a layer of mulch. The different lines empty into shallow mulch-filled basins near trees, shrubs and perennials. As soon as the nutrient-rich grey water comes into contact with the soil, it is immediately fed upon by soil microbes which break it down into its mineral form. Then, it can be taken up by plants and cycled indefinitely. The grey water itself never sees the light of day. This is, of course, a seasonal system that can operate only when freezing is not occurring.

A slightly more complex system, and one which I successfully operated in my urban yard in Edmonton for many years with minimal maintenance, is called a “constructed grey water wetland.” This system involves the creation of a wetland system through which the grey water flows and is purified in the process. It ran from April to October in our case—the water moved by gravity from the main floor bath tub through a 1½- inch PVC line into a series of two “rock and reed” beds outside a few feet from the house. These were 14-inch deep trenches, 12 inches wide and five feet long, lined with rubber and filled with ½ to 1 inch of gravel.

Native wetland plants, such as sweet flag (Acorus calamus) and cattails (Typha latifolia), were planted into the gravel. Bacteria living on the surface of the gravel decompose the nutrients in the grey water (biodegradable soap, dirt, hair, etc.) and turn them into food for the reeds, which grow at a surprisingly robust rate. It is helpful to inoculate the rock and reed beds with healthy local pond water to ensure the presence of appropriate wetland microbes.

By the time the water moves through the rock and reed beds (approximately 48 hours), it is amazingly clean (wetlands are the kidneys of the planet!). The water flowed from the reed beds into a small pond containing additional wetland plants and provided a lovely aesthetic and great habitat for small fish, insects, birds, dragonflies and many other species. As additional water moved into the pond, it overflowed into a mulched woodland garden composed of a variety of native perennial and woody species and edible mushrooms. We drew water from the pond to irrigate nearby garden beds, and regularly harvested the reeds to add to the compost pile, ultimately transforming the ‘waste’ water into biomass, soil and eventually into food.

Using grey water in the landscape is a far simpler and safer process than most people imagine. While we have been the beneficiaries of hundreds of years of evolution in municipal water infrastructure and sanitation planning, we seem to have “thrown the baby out with the grey water” in missing this ubiquitous resource. In addition to the regulatory barriers that may still exist to widespread uptake of grey water recycling, there remains the cultural and emotional resistance that some may feel towards the practice. Those of us in the organic movement, however, may be more accustomed to pushing the social boundaries and creating fertile ground for others to walk upon.

Ron Berezan is an organic farmer and permaculture teacher living on Canada’s west coast in Tla’Amin territory. He works on food security and sustainability projects throughout Canada and in Cuba. theurbanfarmer.ca

Feature image: Cattails filter water. Credit: (CC) Sharon Mollerus.

References 1. National Resources Canada: nrcan.gc.ca 2. Dr. David Schindler: alberta.ca/aoe-david-schindler.aspx 3. Create an Oasis with Grey Water – Choosing, Building and Using Greywater Systems. Art Ludwig. Poor Richard’s Press, Santa Maria, CA. 2006. oasisdesign.net