Ask an Expert: Pollinator Mix

An Important Solution for Conservation of Bees and Other Insect Pollinators

Saikat Kumar Basu

Insects such as bees (Order-Hymenoptera), some species of flies (Order-Dipetra) and beetles (Order-Coleoptera), moths and butterflies (Order-Lepidoptera), under the Class-Insecta and Phylum-Arthropoda constitute an important army of natural pollinators that help in the process of pollination in several important crops and forest trees. Pollination is the process of transfer of pollen grains form anther (male reproductive organ) to the stigma (female reproductive) of the same flower (self-pollination) or a different flower (cross-pollination). Cross pollination is achieved either by non-biological agents like wind, air and water; or via biological agents like different species insects as mentioned above, mollusks (snails and slugs), some species of birds (such as humming birds) and animals (such as bats).

Unfortunately, the populations of insect pollinators like honey bees and native bees are showing drastic reduction over the past few decades due to parasitic diseases, over application of pesticides and other agro-chemicals in the agricultural fields, fluctuations in climatic regimes, ecological and environmental stresses, and lack of ideal foraging habitats for season long abundant food and nutrient supply to mention only a handful across the United States and Canada.

Diversity of native bee species in western Canada. Photo credit: S. Robinson

Over 700 native bee species have been reported in Canada with around 400 species located in Western Canada alone across various habitats and ecosystems. Since the native bee populations across Canada are going down drastically, serious, comprehensive, sustainable and environment-friendly efforts are necessary to successfully conserve bee populations (both native bees and honey bees) and thereby secure the future of Canadian agriculture and apiculture industries from a long term perspective.

Use of pollinator mix or bee mix by Canadian producers such as organic growers can help significantly in promoting the conservation of native bee and honey bee populations across the nation by establishing ideal bee habitats or bee sanctuaries. A pollinator mix is a specially designed seed mix of several annual and/or perennial species of native wild flowers and grasses or annual/perennial wild flower-forage crop mix that can flower over a long period of time and help bees and other insect pollinators by providing them with ideal habitats to forage and nest over an extended period of time.

Pollinator mix can be seeded along the fences of crop fields and ranches, along hard to rich area of the farms, unused or agriculturally unsuitable patches, uphill or downhill farm patches difficult to crop, or unused, undisturbed weedy patches along water bodies, along irrigation canals, low traffic and undisturbed parts of local parks or gardens, backyard kitchens or ideal spots of a hoe lawn, in and around golf courses, provincial parks and gardens.

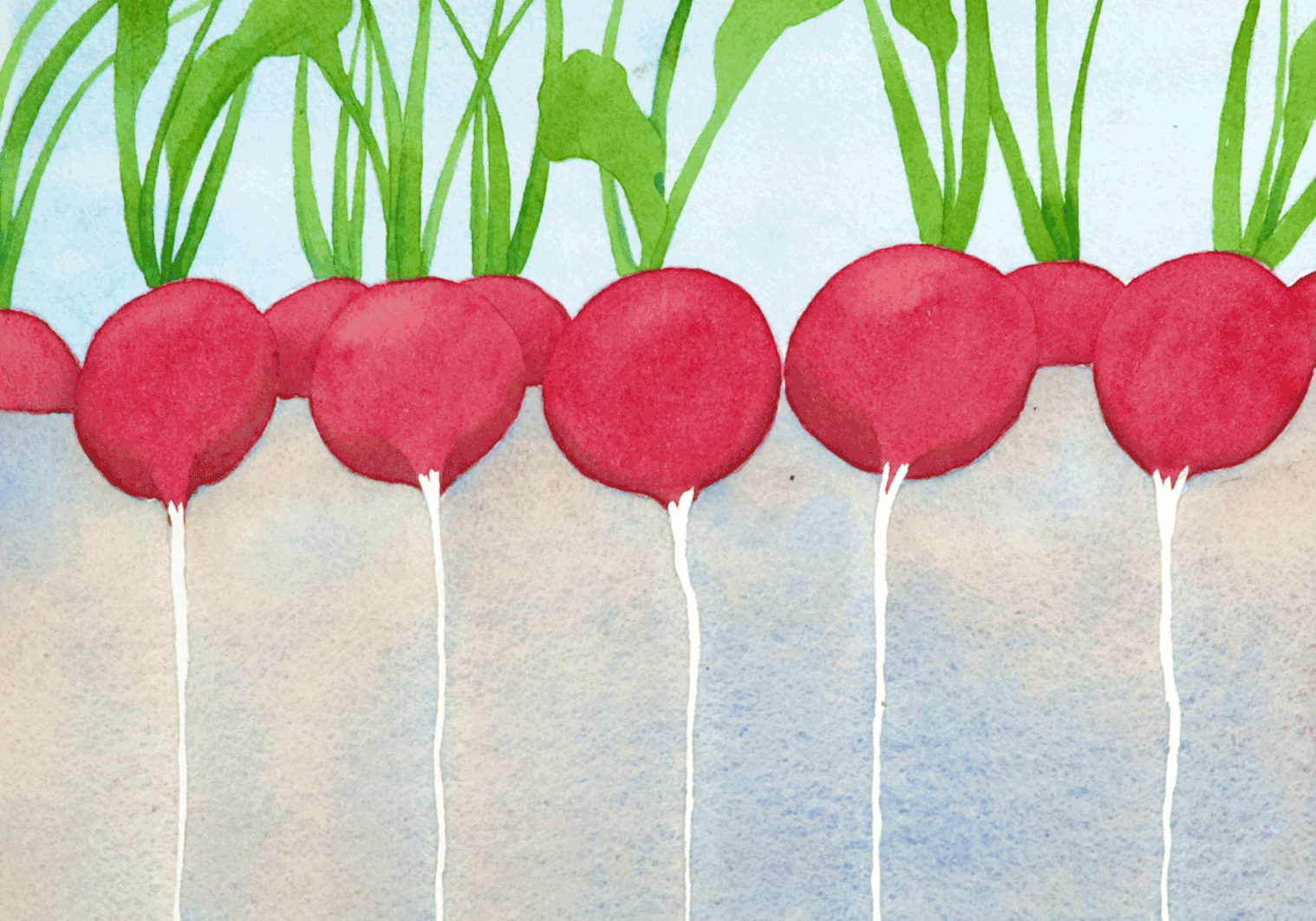

Radish plot attracting native bees. Photo credit: S. K. Basu

Pollinator Mix rich in some annual/perennial forage legumes can also help organic producers to fix nitrogen and micro nutrient deficiencies of the soil, fix nitrogen, and help in building quality bee habitats for pollinator dependent crops like seed canola, seed alfalfa, tomatoes, berry crops, orchard, and forest trees to mention only a few. Creating ideal bee habitats or bee sanctuaries in long or short stretches or commercial production of pollinator mix by organic producers can significantly help the dwindling bee populations of Canada.

How can the Pollinator Mix be useful:

1. Protecting honey bees, native bees, and other insect pollinators, thus allowing pollinators to get established and thrive in their natural ecosystems and helping in the process of pollination.

2. Bee sanctuaries for cities, municipalities, golf courses, ranch, and pastureland or in unused or polluted areas not suitable for agronomic and real estate enterprises can generate green spaces helping secondary target species such as smaller birds and animals to thrive.

3. Bee sanctuaries can also serve as ideal bird habitats for birds such as ducks, geese, pheasants to visit, forage, nest, and hide from predators.

4. Better yield and environment for organic producers growing both pollinator dependent/independent crop systems.

5. Environmental stewardship and establishing better farm environment and environmentally sustainable farm practices for growing pollinator dependent crops by both organic farmers and conventional non-organic crop producers alike.

6. Replacing weedy patches in and around farm area and establishing ideal bee habitats or bee sanctuaries reduces the seasonal outbreak of weeds in the organically producing farm areas.

7. Enrichment in soil quality and soil nutrient profile vital for organic producers to secure quality crop production due to presence of legumes and soil fixers in the Pollinator mix.

8. Utilizing unused areas of farm, hard to reach areas, inaccessible locations, around fences, roadsides, boulevards, around shelter belts, undisturbed and unused parts of the farms, around water bodies, irrigation canals, lakes, ponds, ditches, and swamps could significantly contribute towards increasing the vulnerable Canadian native bee populations.

9. Establishing high quality and sustainable bee sanctuaries in and around pasture, rangelands, and ranches. Pollinator mix with higher proportion of pollinator-friendly forage seed mix could be grown within rangelands left fallow for a season and could be even grazed by animals later in the season when the flowering period is over.

10. Promoting sustainable agriculture.

Fig 4. Annual forage clover: An important forage pollinator species. Photo credit: S. K. Basu

List of some important wildflower species attracting bees and other insect pollinators:

- Erigion (Flea bane)

- Arnica (Wolf bane)

- Aster conspicuus (Showy aster)

- Gaillardia (Blanket flower)

- Allium (Wild onion)

- Asclepias (Milkweed)

- Viccia sp. (Vetch)

- Solidago canadensis (Canada goldenrod)

- Chamerion (Fireweed)

- Achillea millefolium (Yarrow)

- Delphinium (Larkspur)

- Campanula (Hare bell)

- Phacelia (Scorpion weed)

- Dahlia purpurea (Prairie purple clover)

- Helianthus annuus (Annual/Perennial Sunflower)

- Borage officinals (Borage)

- Aquilegia canadensis (Wild columbine)

- Annual/Perennial Gaillardia sp.

- Alyssum maritimum (Sweet Alyssum)

- Myosotis sp. (Forget-Me-Not)

- Nemophila menziesii (Baby Blue Eyes)

- Tradescantia ohiensis (Ohio Spiderwort)

- Echinacea purpurea (Purple Coneflower)

- Rudbeckia hirta (Black-eyed Susan)

Saikat Kumar Basu has a Masters in Plant Sciences and Agricultural Studies. He loves writing, travelling, and photography during his leisure and is passionate about nature and conservation. Department of Biological Sciences, University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, AB, Canada & Performance Seed, Lethbridge, AB; email: saikat.basu@alumni.uleth.ca

Acknowledgement: Performance Seed (Lethbridge, AB), S. Robinson (UFC, Calgary, AB) & W. Cetzal-Ix (ITC, Campeche, Mexico)

Feature image: Bee foraging on wild flower. Photo credit: W. Cetzal-Ix